Endangered Species Monday | Potorous gilbertii - Back From The Brink Of Extinction.

Endangered Species Monday | Potorous gilbertii

This Monday’s (ESP) post, I’ve decided to document a little more on Australia’s wildlife. This Monday I have dedicated this post to one of Australia’s most endangered marsupials. Commonly known as the Gilbert’s Potoroo. (Image Credit Parks and Wildlife Australia).

Identified as the worlds ‘rarest marsupial’, the species is scientifically known as the Potorous gilbertii. Listed as (critically endangered) the species was primarily identified back in 1841 by Dr John Gould FRS - 14 September 1804 – 3 February 1881) who was a British ornithologist and bird artist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists including Edward Lear, Henry Constantine Richter, Joseph Wolf and William Matthew Hart.

Dr Gould has been considered the father of bird study in Australia and the Gould League in Australia is named after him. His identification of the birds now nicknamed “Darwin’s finches” played a role in the inception of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. Gould’s work is referenced in Charles Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species.

Life hasn’t been at all easy for the P. gilbertii. It was only back in 2012 that conservation and environmental scientists (rediscovered) the species of which it was believed the marsupial had gone completely extinct within the wild. Endemic to Australia there is very little known in relation to when threats came about, increased and decreased. However I can state now; as small as populations are known - P. gilbertii’s populations are ‘currently stable within the wild’.

While though populations are stable, there are only thirty to forty actually known to be living within their endemic wild, so there is still a large amount of concern for the worlds most endangered marsupial. Back in early 1980’s the species had been listed as (completely extinct within the wild after studies from the 1800’s turned up nothing). Fortunately though environmental scientists went on the prowl and were not under any circumstances ready to write this species off whatsoever. They were technically looking for an animal that hadn’t been seen since the 1880’s-1990’s. Their work though eventually paid off.

“THEN CAME A BREAK THROUGH IN 1994”

Environmental scientists come 1992-1993 were ready to write the species off, call off all explorations and projects that were aimed at hopefully rediscovering the species. Fortunately though the Australian Parks and Wildlife Service persisted - and come 1994 a spotting was recorded. After so many years believing the Gilbert’s Potoroo had gone extinct, scientists discovered an extremely small population - to the joy of many. Finally there was hope, and today the species remains under full governmental protection.

Native to South-western and Western Australia the remaining populations was taken by three collectors between 1840 and 1879 in the vicinity of King George’s Sound (Albany), but exact locations are unknown. Skeletal material is common in cave deposits between Cape Leeuwin and Cape Naturaliste. Sub-fossil skeletal specimens have been located in coastal sand dunes between these localities. It is currently restricted to Mt. Gardner promontory in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

The entire population (consisting of 30-40 mature individuals) as explained above remains inhabits the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve of which they enjoy protection from the local parks wildlife board. While populations are identified as extremely small, mother will give birth to either 1-2 babies every year, normally its 2 babies. Like kangaroos the species has the ability to keep a second embryo in a state of diapause while the first embryo is growing. If the first baby does not go to term, a second baby starts growing right away.

Check out the Gilbert’s Potoroo Action Group by clicking this link

Diapause is considered a rare phenomena - especially in kangaroos, although its been witnessed quite a lot over the past few years by European, British and Australian Zoologists. The last diapause event (that I’m aware of) was witnessed at the Taronga Zoological Gardens in Australia. You can read the story >here.< The gestation period for Gilbert’s potoroo is unknown, but is estimated to be similar to the long-nosed potoroo at 38 days.

Since so few are alive today, much of the reproductive cycle for Gilbert’s potoroo remains unknown. However, the main breeding period is thought to be November–December with similar breeding patterns to those of the long-nosed potoroo. Scientists have tried to breed them in captivity, but recent attempts have been unsuccessful, citing diet, incompatibility, and age as possible factors that influenced the lack of reproduction. Reproduction in the wild is thought to be progressing successfully as many females found in the wild are with young.

Image: Gilbert’s Potoroo. Photographer Mr Dick Walker.

In 2001, the Gilbert’s Potoroo Action Group was formed to help in the education and public awareness of the potoroo. The group also helps with raising funds for the research and captive-breeding programs for Gilbert’s potoroo. In efforts to protect the remaining population, three Gilbert’s potoroos (one male and two females) were moved to Bald Island in August 2005, where they are free from predation. Since that time, an additional four potoroos have been sent to establish a breeding colony.

THREATS

Fire is the critical threat (present and future) to this species as the Mt. Gardner population is in an area of long unburnt and extremely fire prone vegetation, and a single fire event could potentially wipe out the species (except for the few individuals in captivity and on Bald Island). This species is in the prey size range of both feral cats and foxes, and both are known to exist in the Two Peoples Bay area, thus this species is likely threatened by these predators.

Maxwell et al. (1996) states that the reasons for the decline of the species are unknown. Predation by foxes has probably been significant. Changed fire regimes may have altered habitat and/or exacerbated fox and cat predation by destroying dense cover. Gilbert’s notes record it as “the constant companion” of Quokkas, Setonix brachyurus

Unlike Gilbert’s Potoroo, the Quokka, although declining, persists over much of its pre-settlement range. The difference has not been explained. Maxwell et al. (1996) and Courtenay and Friend (2004), suggest that dieback disease caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi threatens persisting populations by eliminating plant symbionts of hypogeal, mycorrhizal fungi which are the principal food of Gilbert’s Potoroos. Altering vegetation structure and eliminating plants that provide food are direct threats to this species.

For now and based on various accounts, research and up to data documentaries. The species is still in danger. As explained above a single large and sporadic fire within the species habitat - could kill off the entire identified populations, which would be a catastrophe. While there is minimal threat from predators such as foxes and feral cats - this could change. So the need for persistent monitoring is a must. Finally we have disease, with populations being so small at around 30-40, any single disease could like fires wipe the entire species out within a single week.

Within the article above I’ve included various links for your immediate attention and information, as well as a link to the main working group that is helping (and doing all they can) to preserve the species. Furthermore I’ve included a donation link for you to donate to the Gilbert’s Potoroo Action Group. While I’m not entirely sure whether you can volunteer, there is a link on the main website below (highlighted: Volunteer Today). Just click the link, follow the instructions and, I’m confident someone will get back to you as soon as possible.

Volunteer Today

Thank you for reading, please don’t forget after reading to share this article, and hit the like button too.

Dr Jose Carlos Depre Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental & Human Science

Endangered Species Monday | Heteroglaux blewitti - Extinction is now Imminent.

Endangered Species Monday | Heteroglaux blewitti - Extinction is now Imminent

This Mondays (ESP) article (Endangered Species Article), I am am documenting yet again on a species of forest owl (being the third time). This time I know for sure the species is going to go extinct - and sadly there is little that can be done to preserve the bird, although environmentalists are still battling, unfortunately it’s not looking good at all. (Image Credit: Birds of the Bible for Kids).

Listed as (critically endangered), the species was identified back in 1873 by Dr Allan Octavian Hume CB (6 June 1829 – 31 July 1912) was a civil servant, political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress, a political party that was later to lead in the Indian independence movement. A notable ornithologist, Dr Hume has been called “the Father of Indian Ornithology” and, by those who found him dogmatic, “the Pope of Indian ornithology.”

As an administrator of Etawah, he saw the Indian Rebellion of 1857 as a result of misgovernance and made great efforts to improve the lives of the common people. The district of Etawah was among the first to be returned to normalcy and over the next few years Dr Hume’s reforms led to the district being considered a model of development. Dr Hume rose in the ranks of the Indian Civil Service but like his father Joseph Hume, the radical MP, he was bold and outspoken in questioning British policies in India.

He rose in 1871 to the position of secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture, and Commerce under Lord Mayo. His criticism of Lord Lytton however led to his removal from the Secretariat in 1879. Back in 1988 the Forest Spotted Owlet was listed by environmentalists as threatened. Unfortunately since the 1980’s habitat destruction, poaching, deforestation and gradual human population increases have skyrocketed.

“CONTRADICTIONS”

Conservationists allegedly from 1994-2012 battled hard to preserve the species of Spotted Owlet, regrettably their battles have been lost. Back in 2013 a further census was undertaken of which proved the species was nearing complete extinction within the wild. Today (2016) its incredibly likely we’ll lose the Spotted Owlet from all of its range.

Endemic only to India there is estimated to be (from the last census of 2013) a depressing total of 50-260 mature individuals remaining. The total number of “sub-populations has been identified as 2-100. Furthermore within the past ten years from 2006-2016 there has a been “ALLEGEDLY” a continuous population decrease of exactly 10%-19%. International Animal Rescue Foundation India has also reported within the past four years that “very small populations known are still decreasing”, and from records kept the species is highly likely to be extinct within the next 730 days, which is exactly two years.

Image credit: Ashley Banwell / World Birders

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature RED LIST have ‘deliberately lied’ and ‘misinformed the general public’ stating the the bird listed hereto was extant from the years of 1988-1996. Conservationists from International Animal Rescue Foundation India in New Delhi hasn’t no reports from 1988-1996 because the bird was only re-discovered in 1997 after it was described in 1873, and it was not seen after 1884 and considered extinct until it was rediscovered 113 years later in 1997 by Pamela Rasmussen. Source: Ripley, S. D. (1976). “Reconsideration of Athene blewitti (Hume).”. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 73: 1–4.

So whatever the IUCN are talking about is either codswallop or deliberate misinformation to garner further donations from the public?. I mean how on earth can one make this absurd lie up? Maybe the IUCN can produce documented evidence that proves the species has been active from the 1980’s to 1997? I highly doubt that they can, furthermore this lie (among many more) also brings into question any other lies the organisation “may have been publishing within the public domain” to misinform the general public?

Moving on - the population is estimated (as explained) to number 50-249 mature individuals based on the number of records from known sites, with c. 100 individuals now recorded from Melghat Tiger Reserve. This estimate is equivalent to 75-374 individuals in total, rounded here to 70-400 individuals. Given the increasing number of records and sites known within its range it may prove to be more common than previous evidence has suggested.

Trend Justification: The species faces a number of threats which in combination are suspected to be causing a decline at a rate of 10-19% over ten years.

THREATS

Listed on CITES APPENDIX I (The highest listing) meaning all hunting, poaching and any trade of this species is strictly forbidden (unless otherwise stated). Given its rarity, identification of threats is difficult. Forest in its range is being lost and degraded by illegal tree cutting for firewood and timber, and encroachment for cultivation, grazing and settlements, as well as forest fires and minor irrigation dams.

The site of its initial discovery in 1872 (Chhattisgarh) has completely been encroached by agriculture. Large areas of forest in the Yawal Wildlife Sanctuary and Yawal Forest Division as well as the Aner Wildlife Sanctuary and the Satpuda mountain ranges in Maharashtra have recently been subject to encroachment leading to habitat loss for this species.

It is likely that other forest areas where it occurs are under similarly intense pressure. Overgrazing by cattle may reduce habitat suitability. The proposed Upper Tapi Irrigation Project threatens 244 ha of prime habitat used by the species. It suffers predation from a number of native raptors, limiting productivity, and it faces competition for a limited number of nesting cavities.

The species is hunted by local people and body parts and eggs are used for local customs, such as the making of drums. Pesticides and rodenticides are used to an unknown degree within its range and may pose an additional threat.

These owls typically hunt from perches where they sit still and wait for prey. When perched they flick their tails from side to side rapidly and more excitedly when prey is being chased. It was observed in one study that nearly 60% of prey were lizards (including skinks), 15% rodents, 2% birds and the remaining invertebrates and frogs. When nesting the male hunted and fed the female at nest and the young were fed by the female.

The young fledge after 30–32 days. The peak courtship season is in January to February during which time they are very responsive to call playback with a mixture of song and territorial calls. They appear to be strongly diurnal although not very active after 10 AM, often hunting during daytime. On cold winter mornings they bask on the tops of tall trees. Filial cannibalism by males has been observed.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose Carlos Depre - PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical & Human Scientist.

www.speakupforthevoiceless.org

Endangered Species Monday: Rhinoceros sondaicus

Endangered Species Monday: Rhinoceros sondaicus

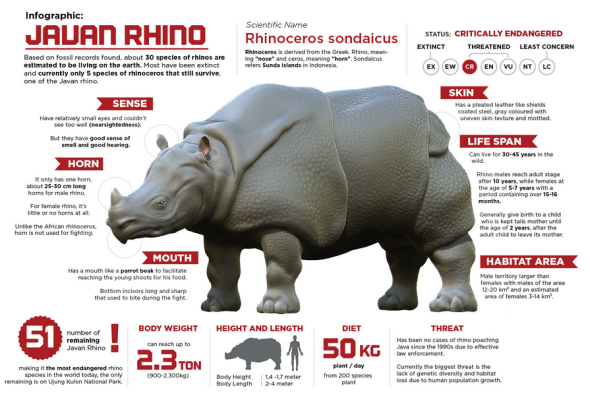

This Endangered Species Post (ESP) Monday I have decided to touch up on the current fate of the critically endangered Javan Rhinoceros of which scientists this month caught yet another rare glimpse of this rather elusive beast within their still natural habitat. (Pic Javan Rhinoceros)

The Javan Rhinoceros was identified back in 1822 by Dr Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (March 6, 1784 – June 4, 1838) was a French zoologist and author. He was the son of Nicolas Desmarest and father of Anselme Sébastien Léon Desmarest. Desmarest was a disciple of Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart, and in 1815, he succeeded Pierre André Latreille to the professorship of zoology at the École nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort. In 1820 he was elected to the Académie Nationale de Médecine.

Unlike the African black and white rhino, you’d be very lucky to catch a glimpse of this stunning specimen of which is classified as a sub-species of the four extant Rhinoceros and, is nearing complete extinction within the wild. Furthermore the subspecies of the Javan Rhinoceros are all extinct too. Known as Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus, Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus, and Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis the three sub-species went extinct from 1930-2011. Below I have included the “documented dates” of extinctions for the three sub-species to the Javan Rhinoceros.

- Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus (extinction was formally documented from 1999, however this report needs to be backed up with further historical data to pinpoint an exact extinction and location).

- Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus (extinction was formally recorded in 2010, however reports state the very last male was located dead within Viet Nam back in 2011).

- Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis (extinction was formally recorded back in 1925).

Please note the Wikipedia article online has confused the (extanct) R. sondaicus with the (extinct) subspecies Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus.

From 1965 Rhinoceros sondaicus was considered ‘extremely rare’ within the wild, then from 1986 to 1994 the species was classified as (endangered). Unfortunately from 1996 the species was again re-classified as (critically endangered) and now no fewer than sixty individuals remain within the wild. The last sighting of ‘a’ Javan rhino was I believe on the 18th September 2015 at exactly 17:46 hrs within the Ujung Kulon National Park.

Javan rhino’s did cover quite an extensive area ranging from Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Viet Nam, and probably southern China through peninsular Malaya to Sumatra and Java. Sadly the species is now thought to be inhabiting the Ujung Kulon National Park which is located within Indonesia. Further non-viable (all male) and elderly populations are also claimed to be inhabiting a very small area of Viet Nam.

To date the species is now endemic only to Indonesia, however there are said to be few individuals ‘possibly’ remaining within Viet Nam too. I must stress though that there has been no official camera trap sightings or actual eyeball sightings of the species in as many years within Viet Nam of which its likely the species “may have gone extinct”.

Regional extinctions of the current sub-species have occurred within the following countries; Bangladesh; Cambodia; China; India; Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia); Myanmar and Thailand. Reports from the 18th September 2015 have also confirmed that the species has taken some ‘fifty years’ to double in size from (50) to now (60) individuals remaining.

From the middle of the nineteenth century the species was practically eradicated due to over-hunting, unregulated hunting, poaching, disease and habitat destruction. The last records of the Javan Rhinoceros within locations not listed above were from 1920 in Myanmar, to 1932 in Malaysia, and 1959 on Sumatra (Indonesia). Up to date records have proven further sightings this year and last year within Indonesia’s Ujung Kulon National Park. The last “known” poached Javan Rhino (sub-species) was said to be from 2010-2011 which was that of the Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus species of which “complete extinction” was formally documented in relation to this specific sub-species of the Rhinoceros sondaicus.

The exact number of individuals noted within the wild is said to be in between 40-60 individuals however due to such small “fragmented locations” its quite difficult at times to know just how many do actually remain, hence the need for increased conservation projects, funding and anti poaching operations to increase. On a good note we know the species is reproducing, unfortunately on a bad note 40-60 individuals is considered near extinct and drastic measures need to be implemented sooner rather than later to preserve the remaining wild specimens.

The second “alleged” location and I stress alleged of the Rhinoceros sondaicus occurs in and around the Cat Loc part (Dong Nai province) of the Cat Tien National Park in Viet Nam, with maybe as few as six individuals remaining. Please do remember not to confuse the extinction of the Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus within the same country (Viet Nam) with the Rhinoceros sondaicus that’s considered still extant although possibly believed to be extinct within (Viet Nam). (I will be providing an update in relation to the alleged Cat Tien Javan Rhino R. sondaicus) via my main Facebook site and will correct amend this document accordingly.

Something I do find rather peculiar is that there are currently no Javan Rhinoceros within protective captivity. Records have stated that some twenty two individuals have been recorded within protective captivity though. I do find this rather strange as we have in zoological gardens around the world just about every other species of Rhinoceros to protect its current future for reintroduction back into the wild at a later date - yet the Javan Rhinoceros has literally been left to its own demise. I’ve yet to locate any real reasonable explanation as to why from the mid 1980’s some individuals were not removed from the wild and bred within protective captivity.

Image: Javan Rhinoceros information graph.

The Javan Rhinoceros currently occurs in lowland tropical rainforest areas, especially in the vicinity of water. The species formerly occurred in more open mixed forest and grassland and on high mountains. Because of its rarity, little is known about its preferred habitat, but it is certainly not naturally restricted to dense tropical forest water. Little is known about the species’ biology and the habitats in which the two remaining populations are found may not be optimal.

The home range size of females is probably no more than 500 ha, while males wonder over larger areas, with likely limited dispersal distance. The species is generally solitary, except for mating pairs and mothers with young. Its life history characteristics are not well known, with longevity estimated at about 30-40 years, gestation length of approximately 16 months (as with other rhino species), and age at sexual maturity estimated at 5-7 years for females and 10 years for males. -IUCN.

Unlike their African relatives the Javan Rhinoceros has a rather small single black horn (typical of Asiatic rhinos). The black market for rhino horns varies with species and price of current horn however it must be noted that the “rarer” the species the more value the horn will provide to the seller. Your average African Rhinoceros horn fetches in the region of $60,000 to $80,000 per kilogram on the black market. However the Asiatic Rhinoceros horn[s] can fetch over or even double this should the species be considered extremely rare.

On a recent visit to Viet Nam I was viewing more Asiatic antique Rhinoceros horn on the black market still selling at higher prices than African rhino horns, however not once did I locate any fresh African horns (2014). So again the need to drastically increase conservation actions, funding and anti poaching patrols is greatly needed. In my own opinion there seems to be way too much funding and awareness pushed into Africa with little progress being seen. Whereas in relation to the Asian Rhinoceros, funding and awareness identical to whats being witnessed in Africa is not even a fraction seen within Asia.

Threats

The cause of population decline is mainly attributable to the excessive demand for rhino horn and other products for Chinese and allied medicine systems. The bulk of the remaining population occurs as a single population within a national park and the population size in Ujung Kulon National Park is probably limited to the effective carrying capacity of the area (around 50 animals). One possible threat to this population is disease. In addition, such a small population faces a constant threat from poachers, although there is evidence that current poaching levels are under control. The Cat Loc population may be too small to be viable, and no breeding has been observed for many years, and it is possible that the animals are too old to breed. The population is so small that all the animals could be of the same sex.

While we have in the past month witnessed new Javan sightings and evidence of reproduction the Javan Rhino is by far nowhere near from danger. As explained above disease could wipe the entire fifty to sixty remaining individuals out. Furthermore while poaching levels are currently under control - it will only take a single individual or group of poachers to gather intelligence on the remaining populations thus exterminating the entire wild populations indefinitely.

My name is Dr Jose C. Depre, thank you reading and please be most kind to share and make aware the current plight of our Asiatic Rhinoceros.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

NB: Please note that while there have been “reported sightings” of the R. sondaicus in Viet Nam there is no up to date data that proves this species is still endemic to the country of Viet Nam.

Endangered Species Friday: Diomedea amsterdamensis - An Ocean of Grief.

Endangered Species Friday: Diomedea amsterdamensis

This Friday’s (ESP) Endangered Species watch Post I dedicate to one of the most stunning and adorable of all plane like birds. Listed as [critically endangered] and identified back in 1983 by South African Dr Jean Paul Roux whom is a Marine Biologist studying Zoology, Systems Biology and Marine Biology at the University of Cape Town, South Africa Jean Paul Roux works full-time at the Department of Biological Sciences, Cape Town. (Image D. amsterdamensis fledglings)

(Image: Birdingblogs.com)

Commonly identified as the Amsterdam Albatross or Amsterdam Island Albatross the species was listed as [critically endangered] back in 2012. This gorgeous bird is endemic to the French Southern Territories of which its populations are continuing to decline at a rapid pace. Populations were estimated at a mere 170 individuals which in turn ranks as the worlds most endangered species of bird. Out of the 170 individuals there are a total of 80 mature individuals consisting of 26 pairs that breed annually.

Between 2001-2007 there were a total of 24-31 breeding pairs annually, which leaves a slightly lower population count today of around 100 mature individuals. Back in 1998 scientists stated that there were no fewer than 50 mature individuals if that. The Amsterdam Albatross doesn’t naturally have a small population however qualified for the category of [critically endangered] due to this reason when identified in 1983. Furthermore pollution, habitat destruction and disease remain pivotal factors that’s decreasing populations furthermore. The video below from MidWay island explains a little more about pollution and birds of this caliber.

Its quite possible that there could be more unidentified groups within the local territory or elsewhere, unfortunately as yet there is no evidence to suggest the Amsterdam Albatross is located anywhere else, however there have been sightings, which do not necessarily count as the species being endemic to countries the bird may have been noted within.

The species breeds on the Plateau des Tourbières on Amsterdam Island (French Southern Territories) in the southern Indian Ocean. An increase of populations was documented via census back in 1984, a year after identification. Marine Biologists have stated that population sizes may have been more larger when its range was more extensive over the slopes of the island.

Meanwhile in South Africa satellite tracking data has indicated the Amsterdam Albatross ranges off the coast of Eastern South Africa to the South of Western Australia in non-breeding pairs. There have been some [possible] sightings over Australia through to New Zealand too. Meanwhile South Africa “may” have its first breeding pair this must not be taken as factual though. Back in 2013 a nature photographer photographed an Amsterdam Albatross off the Western Cape of South Africa which is the very first documented and confirmed sighting [2013].

AN OCEAN OF GRIEF

Breeding is biennial (when successful) and is restricted to the central plateau of the island at 500-600 m, where only one breeding group is known. Pair-bonds are lifelong, and breeding begins in February. Most eggs are laid from late February to March, and chicks fledge in January to February the following year.

Immature birds begin to return to breeding colonies between four and seven years after fledging but do not begin to breed until they are nine years of age. The Amsterdam Albatross exact diet is unknown, but probably consists of fish, squid and crustaceans. During the breeding season, birds forage both around Amsterdam Island and up to 2,200 km away in subtropical waters which is something of interest. During the great Sardine Run many aquatic species consisting of birds, seals, sharks and whales hit the South African oceans hard for sardines. So I am calling on my fellow South African friends to please be on the lookout for this rather elusive bird.

Read more here on the Avian Biology.

Image: Amsterdam Albatross mating ritual, credited to Andrew Rouse.

Diomedea amsterdamensis, is quite a large albatross. When described in 1983, the species was thought by some researchers to be a sub-species of the wandering albatross, D. exulans. Bird Life International and the IOC recognize it as a species, James Clements does not, and the SACC has a proposal on the table to split the species. Please refer to the link above on Avian Biology which will explain more on the bird and its current classification.

More recently, mitchondrial DNA comparisons between the Amsterdam albatross, the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans, the Antipodean albatross D. antipodensis and the Tristan albatross D. dabbenena, provide clear genetic evidence that the Amsterdam albatross is a separate species.

Threats

Degradation of breeding sites by introduced cattle has decreased the species’s range and population across the island. Human disturbance is presumably also to blame. Introduced predators are a major threat, particularly feral cats. Interactions with longline fisheries around the island in the 1970s and early 1980s could also have contributed to a decline in the population.

Today the population is threatened primarily by the potential spread of diseases (avian cholera and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae) that affect the Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross Thalassarche carteri population 3 km from the colony. Infection risks are very high and increased chick mortality over recent years suggests the population is already affected.

The foraging range of the species overlaps with longline fishing operations targeting tropical tuna species, so bycatch may also still be a threat, and a recent analysis has suggested that bycatch levels exceeding six individuals per year would be enough to cause a potentially irreversible population decline. Having a distribution on relatively low-lying islands, this species is potentially susceptible to climate change through sea-level rise and shifts in suitable climatic conditions. Plastic pollution has also been noted as problematic.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa and International Animal Rescue Foundation France are currently working on projects to reduce more plastic within bird habitat that has never been visited by the organisation before. The current plight of bird habitat and plastic pollution within the Pacific ocean needs to be worked on by everyone, furthermore addressed immediately.

To date all twenty two species within the four genera of Albatross are heavily threatened with extinction. There remains no species at present that is listed as [least concern]. The future is indeed very bleak for all 22 species and something we now need to work on and towards to preserve Albatross’s before extinction occurs within a decade for the vast majority of all twenty two species and sub-species.

Thank you for reading.

Please share to make aware the plight of this stunning bird and the remaining twenty two species too.

Dr Jose C. Depre.

Botanical and Environmental Scientist.

A planet without birds is a world not worth living within anymore. Daily I am traumatized and deeply disturbed at viewing the destruction we have caused to these stunning animals and, their natural habitat. I am pained, deeply frustrated and infuriated at international retail companies whom preach good yet practice negligence killing off via plastic pollution our species of birds. Jose Depre

Endangered Species Friday: Ammospermophilus nelsoni

Endangered Species Friday: Ammospermophilus nelsoni

This Friday’s Endangered Species Watch Post (ESP) we focus a little attention on a species of squirrel that’s rarely mentioned within the conservation or animal rights arena. A. nelsoni was identified by Dr Clinton Hart Merriam (December 5, 1855 – March 19, 1942). Dr Merrian was an American zoologist, ornithologist, entomologist, ethnographer, and naturalist. (Image; Archive, A. nelsoni)

Year of identification was back in 1893 of which the species remains endemic and extant to the United States, State of California. Environmentalists undertook two census’s of the species’s current population size, known threats and any new threats to the species back in 1996 and, 2000. Both census’s revealed few changes with regards to current status, of which the species was listed as endangered from 1996 and again in 2000.

Today the San Joaquin Antelope Squirrel as the rodent is commonly know remains at [critically endangered] level. Populations are continuing to decline within a country that one would expect to see good conservation measures increasing population sizes and, eliminating any new and past threats.

To date the current population size remains unknown which “may-well be why the species has qualified for listing on the [critically endangered] list”. Scientists undertook a rather crude population survey on three to ten squirrels per hectare on 41,300 hectares of the best and known remaining habitat. The survey then provided a rough estimate of which stated population sizes could be standing at [124,000 - 413,000]. However as the true population size is currently unknown one must not take this survey into consideration when documenting or teaching students. The following estimates were based on more in-depth multiple crude evaluations back in [1980].

Current “trend” evaluations from 1979 have confirmed that many San Joaquin Antelope Squirrel populations have unfortunately decreased throughout their known range although, even these surveys are still pretty much sketchy. A further trend evaluation survey back in 1980 revealed more-or-less the same findings from (1979) of which the species has decreased through much of its small (clustered range) manly within, San Joaquin Valley, California.

Recent protection efforts in the southwestern San Joaquin Valley likely have to some degree slowed the rate of decline and, the species remains common in [some protected areas]. Probably the rate of decline is less than 30% over the past 10 years. Nevertheless the species is still in decline over much of its range and, despite conservation efforts the San Joaquin Antelope Squirrel is sadly nearing extinction (within the wild).

Data proves for now the species has declined throughout much of its former range by some twenty percent. Back in 1979, extant, uncultivated habitat (but including land occupied by towns, roads, canals, pipelines, strip mines, airports, oil wells, and other developments) for the species was estimated at 275,200 hectares (680,000 acres, 2,752. None of the best historical habitat remained.

One study indicated that densities in open Ephedra plots and shrubless plots ranged from 0.8 to 8.0 squirrels per hectare, but all but two sites had densities of four or less per hectare. Densities on shrubless, grassy dominated sites were equal to or higher than those on shrubby sites.

The San Joaquin antelope squirrel is dull yellowish-brown or buffy-clay in color on upper body and outer surfaces of the legs with a white belly and a white streak down each side of its body in the fashion of other antelope squirrels. The underside of the tail is a buffy white with black edges. Males are approximately 9.8 inches and females are approximately 9.4 inches in length

Breeding normally takes place during late winter to early spring of which young will normally be born from the beginning of March. Female gestation normally lasts no longer than one single month. Young do not normally emerge from the den until around the first or second weeks of April. The San Joaquin antelope squirrel has only one breeding cycle during the entire year of which this is timed just right so that when young are born there is much vegetation and food for young to feed and hide within after weening. Weening of young is believed to start before the young even emerge from the den.

A. nelsoni is omnivorous, feeding mostly on green plants during the winter and insects and carrion when these are available. It occasionally caches food. The squirrels live in small underground familial colonies on sandy, easily excavated grasslands in isolated locations in San Luis Obispo and Kern Counties.

Image: A. nelsoni. Credit (Mark Chappell).

Half of the remaining habitat supports fewer than one animal per hectare, 15% of the remaining habitat supports 3-10 animals per hectare (generally four or fewer per hectare, California Department of Fish and Game 1990). The species Spermophilus beecheyi reportedly may restrict the range of A. nelsoni. Among several predators, badger is most important, and lives in small groups.

Threats

The decline is a result of loss of habitat due to agricultural and urban development as well as oil and gas exploration practices. Primary existing threats include loss of habitat due to agricultural development, urbanization, and petroleum extraction, and the use of rodenticides for ground squirrel control. Overgrazing and associated loss of shrub cover is a concern in some areas. These threats will be alleviated by the implementation of the San Joaquin Endangered Species Recovery Plan. There are some discussions that the current drought within the region “may” have a profound effect onto the species however, this concern remains just that and, no proven data surveys have shown drought to be of a threat as yet.

Thank you for reading and, have a nice weekend from all the team at International Animal Rescue Foundation.

Dr. Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Endangered Species Monday - Procyon pygmaeus

Endangered Species Monday - Procyon pygmaeus

This Monday’s endangered species article I write about a species that I have honestly never even heard of or had the pleasure of meeting. Listed as critically endangered, the species is commonly known as the Pygmy Raccoon or scientifically known as Procyon pygmaeus. (Image: Pygmy Raccoon)

Identified back in 1901 by Dr Clinton Hart Merriam (December 5, 1855 – March 19, 1942), Dr Merriam was an American zoologist, ornithologist, entomologist, ethnographer, and naturalist. Known as “Hart” to his friends, Merriam was born in New York City in 1855. His father, Clinton Levi Merriam, was a U.S. congressman.

Dr Merriam studied biology and anatomy at Yale University and obtained an M.D. from the School of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University in 1879. He taught for a while at Harvard University. Dr Merriam died in Berkeley, California in 1942. I have followed quite a lot of work relating back to Dr Merriam and must say Dr Merriam was one of very few experts of his type within the field of animal studies as we know it.

From 1996 the Pygmy Raccoon that’s known to the locals as the “Cozumel Raccoon” was listed as endangered back in 1996. Endemic to Mexico, Pygmy Raccoon’s are only known to inhabit the Cozumel region off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, hence the carnivores name - “Cozumel Raccoon”.

Recent census counts taking into consideration juveniles gives us an (estimated) population at a depressingly two hundred and fifty mature individuals. However fifty nine per cent of the population actually corresponds to mature individuals which is somewhat concerning, especially when we really need more younger juveniles to continue the gene pool and to ensure that overall protection of the species is to a degree somewhat safe should an outbreak of disease occur.

Taking all data - past - and - present census counts, NEAR exact population size of juveniles we’re still not looking at a high number of individuals however can state that overall population sizes are 192-567 individuals. Due to low population densities, introduction of new species onto the island and the effects of mega-hurricanes this provides environmental scientists justification to place the species at (critically endangered level/criteria).

Due to continuing decline of population sizes with regards to increasingly destructive hurricanes, introduction of new species onto the island, extent of occurrence being in the region of some 500km2, less than five locations the species is known to inhabit on the island the Pygmy Raccoon thus meets the criteria for (endangered listing). Overall and taking both reports into account the species qualifies for critically endangered listing.

Exact location; Cozumel Island (478 km2) off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

Image: Mexico - Pygmy Raccoon.

Back in 2004 a further census was undertaken by Mr McFadden that estimated a near total of some 954 mature individuals (including juveniles). However due to some pretty intense hurricanes and new taxa introduced to the island species populations are still taking a pretty fast downward spiral of which its populations are still noted as (declining).

Due to the species being severely impacted by hurricanes and already depressed populations from a variety of human threats make it increasingly difficult for populations to recover following natural disasters it quite likely were going to witness extinctions occurring very soon. After major hurricanes, the density of Pygmy Raccoon’s can decline at a particular site by as much as 60% and the proportion of juveniles in the population can diminish significantly. The impact of hurricanes may vary among regions or vegetation types on the island.

The species is not legally protected and there are no protected areas on Cozumel Island. Proposed conservation measures include protecting areas inhabited by this species, establishing captive breeding programs, and controlling introduced species. However even with these protective measures in place - we can already state local NGO’s and zoological gardens are expecting the species to be pushed into extinction within the wild due to the fact captive breeding programs are being thought up.

Relatively little is known about the group size of the Raccoon’s. They are primarily nocturnal and solitary animals, but may sometimes form family groups possibly consisting of the mother and cubs. The Raccoon’s live in densities of about 17-27 individuals per km2., and inhabit home ranges of around 67 hectares (170 acres) on average. However, individuals do not appear to defend territories to any great extent, and their close relative, the common raccoon, can exist at very high densities when food is abundant. Although there have been no detailed studies of their reproductive habits, females seem to give birth primarily between November and January, possibly with a second litter during the summer months.

Threats

While legally protected within Mexico threats are still increasing that do look set to push the species into complete wild extinction.

Cozumel Island has been substantially developed for tourism. Cozumel is still relatively well-conserved, with close to 90% of the island covered by natural vegetation, but the situation is deteriorating rapidly. The interior of the island is less developed, but Raccoon’s are rare or absent there. There is only a very small area of prime raccoon habitat and this is on the coast where most of the tourist development is taking place.

The expansion and widening of the road system is fragmenting the vegetation of the island in at least three areas. The widening of roads is potentially increasing their barrier effect and exacerbating their impact on the conservation of Pygmy Raccoon’s and other native species.

Most cases of Pygmy Raccoon mortality documented since 2001 have been the result of animals being run over by cars on the island’s highways. Alien invasive predators, such as Boa constrictor, as well as domestic and feral dogs, may have an important impact on the Pygmy Raccoon population and it is confirmed that feral dogs predate on them.

Additionally, introduced carnivores to the island could easily become a source of parasites and pathogens that could potentially affect negatively Pygmy Raccoon populations. The introduction of congeners from the mainland (P. lotor), usually for pets, is a risk of genetic introgression and a potential source of parasites and pathogens.

Hurricanes are the main natural threat recognized for the Cozumel biota. In the case of the Pygmy Raccoon, hurricanes cause drastic population decline, reduction in the proportion of juveniles, and cause injury and facilitate pathological change. The frequency, magnitude and duration of hurricanes in the Caribbean Basin is increasing (CITA), so they are an issue of major concern as there may be a synergistic effect with anthropogenic disturbance.

Hunting and collection of Pygmy Raccoons as pets is currently not an important threat.

Thank you for reading.

Dr. J.C Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist. CEO

Endangered Species Monday: Pseudalopex fulvipes.

Endangered Species Monday - Pseudalopex fulvipes

In this Monday’s endangered species article we focus our attention on the species of fox commonly known as the Darwin fox. Identified by Dr William Charles Linnaeus Martin (1798 - 1864). Dr Martin was an English naturalist.William Charles Linnaeus Martin was the son of William Martin who had published early color books on the fossils of Derbyshire, and who named his son Linnaeus in honor of his interest in the classification of living things.

Listed as CRITICALLY ENDANGERED the species was scientifically identified as Pseudalopex fulvipes endemic to Chile, Los Lagos. Charles Darwin collected the very first evidence of this rather stunning species back in 1834 however was not the primary identifier despite the species name. Since 1989 the fox has been re-monitored to determine its current population sizes and future classification. I am somewhat skeptical that this species will survive into the next five years even with more in-depth wild analysis - the species in my own expert opinion is doomed.

One fox was observed and captured back in 1999 for data and breeding with a further two adults captured back in 2002 in Tepuhueico. That same year it was noted a local as killing a mother and her cubs which amassed to some four Darwin foxes witnessed dead and alive within the wild since revaluation of species began from 1989. Some evidence although (little documented) has confirmed “sightings” of Darwin foxes during the year of 2002 however, these are sketchy reports.

On mainland Chile, Jaime Jiménez has observed a small population since 1975 in Nahuelbuta National Park; this population was first reported to science in the early 1990s. It appears that Darwin’s Foxes are restricted to the park and the native forest surrounding the park. This park, only 68.3 km² in size, is a small habitat island of highland forest surrounded by degraded farmlands and plantations of exotic trees. This population is located about 600 km north of the island population and, to date, no other populations have been found in the remaining forest in between.

Darwin’s Fox was reported to be scarce and restricted to the southern end of Chiloé Island. The comparison of such older accounts (reporting the scarcity of Darwin’s fox), with recent repeated observations, conveys the impression that the Darwin’s Fox has increased in abundance, although this might simply be a sampling bias.

As explained even with a very, very small increase in sightings - populations are declining and sadly we may be reporting in the next year or two an (extinction in the wild) occurring if not a complete extinction overall. Should that happen we’ve lost the entire species for good.

Darwin foxes are said and known to be forest dwelling mammals which could be why environmental surveys are proving to be fruitless. Darwin foxes occur only in southern temperate rainforests. Recent research on Chiloé, based on trapping and telemetry data on a disturbance gradient, indicates that, in decreasing order, foxes use old-growth forest followed by secondary forest followed by pastures and openings. Although variable among individuals, about 70% of their home ranges comprised old-growth forest.

Protected under Chilean law since 1929 the Darwin fox are listed on Cites Appendix II (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species wild flora and fauna). Conservation actions that are under way in the Nahuelbuta National Park are to increase species populations and establish overall protection within this range. Temuco zoo did hold one single species of which was believed to be held for protective captive breeding however the fox has since died back in 2000.

Threats

Although the species is protected in Nahuelbuta National Park, substantial mortality sources exist when foxes move to lower, unprotected private areas in search of milder conditions during the winter. Some foxes even breed in these areas. This is one of the reasons why it is recommended that this park be expanded to secure buffer areas for the foxes that use these unprotected ranges.

The presence of dogs in the park may be the greatest conservation threat in the form of potential vectors of disease or direct attack. There is a common practice to have unleashed dogs both on Chiloé and in Nahuelbuta; these have been caught within foxes’ ranges in the forest. Although dogs are prohibited in the national park, visitors are often allowed in with their dogs that are then let loose in the park.

There has been one documented account of a visitor’s dog attacking a female fox while she was nursing her two pups. In addition, local dogs from the surrounding farms are often brought in by their owners in search of their cattle or while gathering Araucaria seeds in the autumn. Park rangers even maintain dogs within the park, and the park administrator’s dog killed a guiña in the park. Being relatively naive towards people and their dogs is seen as non-adaptive behaviour in this species’ interactions with humans.

The island population appears to be relatively safe by being protected in Chiloé National Park. This 430 km² protected area encompasses most of the still untouched rainforest of the island. Although the park appears to have a sizable fox population, foxes also live in the surrounding areas, where substantial forest cover remains. These latter areas are vulnerable and continuously subjected to logging, forest fragmentation, and poaching by locals. In addition, being naive towards people places the foxes at risk when in contact with humans. If current relaxed attitudes continue in Nahuelbuta National Park, Chiloé National Park may be the only long-term safe area for the Darwin’s Fox.

No commercial use. However, captive animals have been kept illegally as pets on Chiloé Island.

Current estimates place the species population count at a mere 250 left within the wild.

Thank you for reading.

Please share and lets get this fox the protection it requires through education, awareness and funding.

Links for interest:

Dr Jose C. Depre.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa.

Donate to Say No To Dog Meat today.

Corroboree Frogs - Critically Endangered

Corroboree Frogs are amongst the most visually spectacular frogs in the world and are Australia’s most iconic amphibian species. Listed as critically endangered, the two species have several differences between them, including colour, patterns and even skin biochemistry.

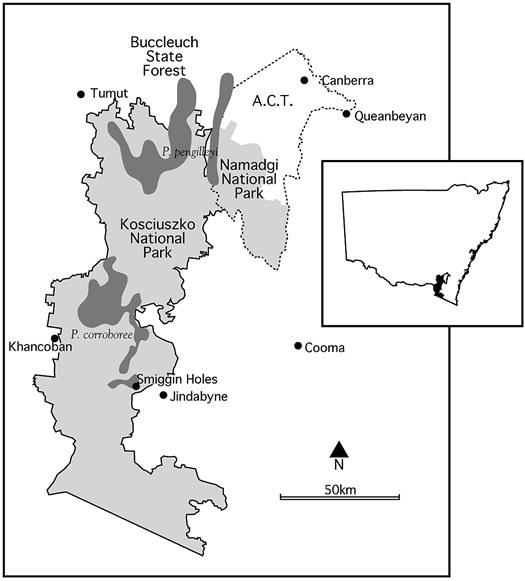

The frogs are around 3centimetres in length and only live in the sub-alpine regions within Kosciuszko National Park, from Smiggin Holes in the south, and northwards to the Maragle Range. Southern Corroboree Frogs only occur between about 1300 and 1760 m above sea level.

Breeding

Habitat which is critical to the survival of Corroboree Frogs includes both breeding habitat and nearby areas where they feed. The frogs have to be four years old before they can begin to reproduce and adults only have one breeding season around December, when males build chamber nests within grasses and moss near shallow pools, seepages and so on.

Corroboree Frogs tend to breed in water bodies that are dry during the breeding season. Outside the breeding season, Corroboree Frogs have been found sheltering in dense litter and under logs and rocks in nearby woodland and tall moist heath. Northern Corroboree Frogs have been found to move over 300 metres into surround woodland after breeding.

The diet of Corroboree Frogs consists mainly of small ants and, to a lesser extent, other invertebrates. Typically, the pools are dry during the breeding season when the eggs are laid. The males have three call types: an advertisement call, threat call, and courtship call.

Males woo their lady-frogs by singing. Each male will attract up to ten females to his burrow sequentially and may dig a new burrow if his first is filled with eggs.

If a female is attracted to a male, she will lay her eggs in his nest. The male will remain in his nest through the breeding season and may accumulate many clutches. Clutch size for Corroboree Frogs is relatively low for a frog species; 16 to 38 eggs per female.

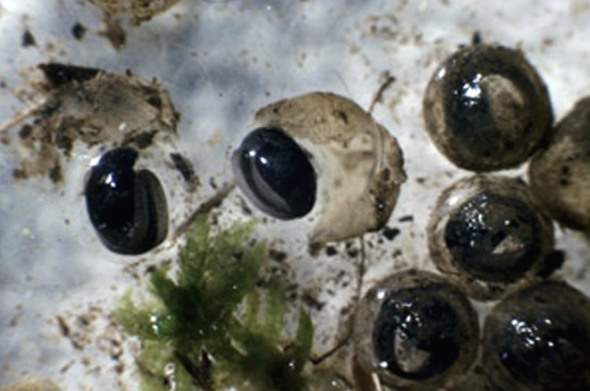

Within the nest, the eggs develop to an advanced stage, before development stops and they enter what is called ‘diapause’. This effectively means that the embryos remain, without developing further, until flooding of the nest following autumn or winter rains stimulates them to hatch.

After hatching, the tadpoles move out of the nest site and into the adjacent pool where they live for the remainder of the larval period as a free swimming and feeding tadpole. Corroboree Frog tadpoles are dark in colour, have a relatively long paddle shaped tail, and grow to 30 mm in total length. The tadpoles continue growing slowly, particularly over winter when the pool may be covered with snow and ice, until metamorphosis in early summer.

Corroboree frogs are the first vertebrates discovered that are able to produce their own poisonous alkaloids, as opposed to obtaining it via diet as many other frogs do. The alkaloid is secreted from the skin as a defence against predation, and potentially against skin infections by microbes. It has been described as potentially lethal to mammals if ingested. The unique alkaloid produced has been named pseudo-phrynamine.

Corroboree frogs hibernate during winter under whatever shelter they can find. This may be snow gum trees, or bits of bark or fallen leaves. Males stay with the egg nests and may breed with many females over the course of one season.

Conservation status

Both species have declined dramatically in the past thirty years. However, the Southern Corroboree Frog has suffered from more serious declines.

Current status

The Southern Corroboree Frog, as of June 2004 had an estimated adult population of 64. This species has suffered declines of up to 80% over the past 10 years. It is found only within a fragmented region of less than 10 km² within Mount Kosciuszko National Park in the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales. It is only found at 1300 m above sea level (Osborne 1989). It is currently listed as critically endangered and is considered to be one of, if not, Australia’s most endangered species.

The Northern Corroboree Frog is more widely distributed across about 550 km² of the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges in Namadgi National Park, Australian Capital Territory, and Kosciuszko National Park and Buccleuch State Forest in New South Wales. It is found above about 1000m and is found to have higher population numbers at lower elevations. It has recently been downgraded from critical to endangered by the IUC finding.

Cause for decline

The near-loss of these frogs has been attributed to a variety of causes, such as habitat destruction from recreational 4WD use; development of ski resorts; feral animals; degradation of the frogs’ habitat; the extended drought cycle affecting much of southeastern Australia at present; and increased UV radiation flowing from ozone layer depletion.

The drought affects these frogs by drying out their breeding sites so that the breeding cycle, which is triggered by seasonal changes and may require moistening of the bogs in autumn and spring to bring on specific developmental events, is delayed. This may mean that tadpoles have not metamorphosed by late summer when their bogs dry out, and so perish. The bogs themselves are apparently drier than usual.

Severe bushfires in the Victorian and NSW high country in January 2003 destroyed much of the frogs’ remaining habitat, especially the breeding sites and the leaf litter that insulates overwintering adults. The fire affected almost all Southern Corroboree Frog habitat, however recent surveys have shown that the fire resulted in a lower than expected decline in population.

As with many other Australian frogs, the predominant reason for the Corroboree Frogs’ decline is thought to be infection with the chytrid fungus. This fungus is believed to have been accidentally introduced to Australia in the 1970s and destroys the frogs’ skin, usually fatally. Corroboree frogs’ eggs appear to be immune. Frog populations may eventually be able to acquire immunity, as wild relatively healthy adults have been found with the fungus on their skin.

Conservation efforts

The Amphibian Research Centre had already begun a rescue programme under which eggs were collected and raised to late tadpole stage before return as close as possible to their collection site. Research is now underway into captive breeding and on which lifecycle stage - eggs, tadpoles or adults - promises the best chance of survival following return to the wild.

The national parks authorities in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and Victoria have developed conservation programmes, including a captive husbandry programme at Tidbinbilla, ACT, Taronga Zoo in Sydney, as well as Zoo’s Victoria at Healesville Sanctuary.

The two species are the Southern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree) and the Northern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne pengilleyi).

To read more on Corroboree Frogs and how to help them: www.corroboreefrog.com.au

Thank you for reading.

Michele Brown.