Endangered Species Monday | Brachylophus fasciatus.

Endangered Species Monday | Brachylophus fasciatus

This Monday’s (ESP) Endangered Species Watch Post report I document on a rather “undocumented species” of iguana identified back in the 1800’s. (Photographer unknown)

Identified back the 1800’s, and listed as [endangered] the species was originally identified by French Dr Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 1770 – 7 October 1847) who was a French chemist, mineralogist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris.

Dr Alexandre Brongniart was born in Paris, the son of the architect Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart and father of the botanist Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart. He was an instructor at the École de Mines (Mining School) in Paris and appointed in 1800 by Napoleon’s minister of the interior Lucien Bonaparte director of the revitalized porcelain manufactory at Sèvres, holding this role until death.

The young man took to the position a combination of his training as a scientist— especially as a mining engineer relevant to the chemistry of ceramics— his managerial talents and financial acumen and his cultivated understanding of neoclassical esthetic. He remained in charge of Sèvres, through regime changes, for 47 years.

Commonly known as the Fiji Banded Iguana, Lau Banded Iguana, South Pacific Banded Iguana, or Tongan Banded Iguana the species is unfortunately endangered and nearing extinction within the wild. A reptilian, and member of the iguana family the species has been placed within the order of (Squamata).

Within the past TWO DECADES the species has undergone a decline of some 50% throughout its range. Furthermore species declines are still ongoing with no apparent let up neither, (threats have been noted as significantly severe and widespread).

Without conservation intervention, the degradation observed during the last 20 years is predicted to cause further declines over the next 20 years that approaches 80% and potentially will be found to be even higher with further population analysis. Basically unless conservation efforts are improved or continue then we will lose the species very quickly.

Image: Fiji Banded Iguana (Credits: Robin Carter)

Now to some humans this may not seem much to worry about. However let me ask you this. Have you experienced a rather large number of flies bothering you, mosquitoes, insects, and general bugs wreaking havoc with your everyday life? If the answer is “yes”, then maybe you need to be paying attention to my articles. Reptiles loves flies, and without reptiles there will be more flies.

Endemic to Fiji, the species has recently been introduced to Tonga. Among all the islands surveyed for the presence of Lau Banded Iguana, only on the two Aiwa Islands were enough lizards found to estimate a population size, this was estimated to number less than 8,000. That population size is concerning (especially when we take into consideration life span, gestation, and threats). 8,000 can soon turn into 1000 in under five years.

Although there is no official “population size estimates”, its believed from census reports (which I myself do question), within the past 35-40 years the species has undergone (as explained above) a decline of 50%. Discussions with island residents indicate that on most islands the iguanas are now more rare than they had been in the recent past.

Most islands in the region are now inhabited and iguanas were generally found in degraded forests or remnant forest patches, but not in proximity to villages or gardens. Surprisingly, among the uninhabited islands surveyed only one was found to have iguanas present, but this is likely due to the abundance of cats present on the iguana-free islands. It is known that local residents intentionally translocate kittens to these uninhabited islands for rat control.

In summary, a total of 52 islands in the Lau Group and Yasayasa Islands were visited between 2007 and 2011 and iguanas were detected or reported from only 11 islands, with an additional report from one island that was not visited. The sheer fact we only have on ELEVEN ISLANDS instead of FIFTY TWO Fiji Banded Iguanas, just goes to show we have serious problems here that need addressing before its to late.

Iguanas were abundant on only three islands, the two neighbouring Aiwa Islands and Vuaqava, all of which are uninhabited. Goats have recently populated all three of these islands and Vuaqava has a seemingly large cat population (which could be a threat). Most of these 53 islands should have had resident iguana populations. For example, two islands with historic populations, Moce and Oneata, were described by the Whitney Expedition and have since been extirpated. Given these results, it appears that iguanas could be remaining on about 20% of the islands in the region and are abundant on only 5%.

“SO WHAT ARE THE THREATS?”

The current band at which the Fiji Banded Iguana sits in (in regards to known population levels) is 8,000 120,000 mature individuals. Now that doesn’t mean we have 8,000 or 120,000 mature individuals. The current band basically means what we have “assumed the population” based on very sketchy and rough census estimates. What we do know, is that from the last census conducted only 8,000 were eye balled (meaning that 8,000 were physically witnessed). Further census counts are underway.

Lau Banded Iguanas are sometimes locally kept as pets, and this was observed on three different islands during surveys in 2011. Historically, these iguanas would have been a local food source, similar to the larger extinct species (Lapitaiguana and B. gibbonsi) in the region, but there are no recent records of human consumption. The black market trade in Brachylophus does not include this species and is unlikely to be a threat in the future as its remaining localities are very remote.

Black Rats (Rattus rattus) and feral cats (Felis catus) are the main mammalian predators threatening the persistence of iguanas and are capable of causing local extinctions in a relatively short time period. Fortunately, mongoose has not been introduced to the Lau Group yet, and maintaining it free of them is an important biosecurity issue. On a few islands, free-roaming domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) were observed to cause major disturbance in small forest patches, turning large areas to bare mud that is no longer suitable for iguana nesting.

Even in the absence of goat herding, forest burning is widespread and is increasingly one of the biggest threats to iguana habitat and their persistence. Continued deforestation on the small islands where Lau Banded Iguanas remain is predicted to cause additional local extinctions over the next 40 years. In particular, on the large islands of Lakeba and Vanua Balavu where iguanas should have been numerous, there has been significant forest loss through deforestation, burning, and fragmentation.

Image: Fiji Banded Iguana (Photographer unknown).

Additional threats to the native forests include further development of urban and village areas, plantation agriculture, and logging. In particular, harvesting Vesi Tree (Intsia bijuga) for use in traditional carving on several islands (for example, Kabara) has significantly reduced the native forest. Forest conversion to Caribbean Pine plantations is also significant, especially on Lakeba.

Proposed development of tourism resorts, on the smaller islands in particular, has significant impacts on these habitats, possibly leading to losses of entire iguana populations as has been observed elsewhere in Fiji. Finally, proposed new cruise ship routes to the remote Lau islands will require construction of new infrastructure and is likely to be a source of invasive species from Viti Levu unless strict biosecurity measures are enforced.

The impact of the recent introduction and spread of the invasive alien Common Green Iguana (Iguana iguana) in Fiji are not yet known for this species but have been shown to have significant detrimental effects everywhere they have been introduced. Eradication for this invasive now appears unlikely, and it is possible the Green Iguana will continue to spread to other well-forested islands despite eradication efforts. Green Iguanas are vastly more fecund and aggressive than native iguanas and may have significant effects on remnant small island populations.

At minimum, this introduction has caused considerable confusion in the local education programmes aimed at protection of Banded Iguanas versus eradication of the Green Iguanas, since juveniles of the latter appear superficially similar. The northern Lau Islands are very close to Qamea where the Green Iguana was first introduced and are at high risk of invasion.

Irruptions of invasive alien Yellow Crazy Ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) are known to occur on many of the southern Lau islands. Even though these ants were introduced to Fiji over 100 years ago, it is not understood what causes populations to periodically irrupt in huge numbers on some islands. When Crazy Ants irrupt, the entire ground surface, shrubs, and trees are entirely covered with ants and it has been observed that native skink and gecko abundance drops greatly during this time.

The impact of aggressive ant irruptions on iguana reproduction and recruitment is not known, but is likely to suffer similarly to other lizards. Lau Banded Iguanas are sometimes locally kept as pets, and this was observed on three different islands during surveys in 2011 (as explained above).

Historically, these iguanas would have been a local food source, similar to the larger extinct species (Lapitaiguana and B. gibbonsi) in the region, but there are no recent records of human consumption. The black market trade in Brachylophus does not include this species and is unlikely to be a threat in the future as its remaining localities are very remote.

Listed as endangered, the current future is not as yet known. However what we do know is that the Fiji Banded Iguana does not inhabit the ground it once did. Threats are wide, and the species has undergone a large population decline.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical and Human Science.

Endangered Species Friday: Macrotis lagotis | Bandicoot.

Endangered Species Friday | Macrotis lagotis

This Fridays (ESP) [Endangered Species Post] I touch up on the Macrotis lagotis, commonly known as the Rabbit-eared Bandicoot identified back in 1837 By Dr Reid. (Image credit unknown, explorer unknown).

The Rabbit Eared Bandicoot is the fifth Australian marsupial that I’ve documented on since establishing the (Endangered Species watch Post), covering now over 403 species of animals (worldwide) in exactly 5 years. From 1965 very little was actually known about the Rabbit Eared Bandicoot, despite the fact it was formally identified way back in the 1800’s.

Unfortunately when scientists eventually managed to re-locate the species, they found the animal was in fact nearing extinction within its endemic wild. Listed then as (ENDANGERED) the species almost went extinct from the 1980’s - 1900’s. Fortunately environmental scientists worked hard to preserve this rather unusual animal. From 1990 the species was still listed as (endangered - and nearing complete extinction within the Australian wild).

Fortunately from 1994-1996 species recovery programs increased populations within the wild. Come 1996 the species was re-listed as (vulnerable). Commonly known as the ‘bilby’, M. lagotis once inhabited some 70% of Australia. Wild populations are now restricted predominantly to the Tanami Desert (Northern Territory), the Gibson and the Great Sandy Deserts (Western Australia), and one outlying population between Boulia and Birdsville (south-west Queensland). The bilby has gone extinct from portions of southern Queensland within the last few decades.

However despite numerous conservation actions that have been aiding and increasing bilby populations, they are now on the decrease; slowly, but surely, for how long though is another story. Endemic to Australia (Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia) its believed there are no fewer than 500 individuals on Thistle Island, 500 in Arid Recovery, 100 in Venus Bay, 200 in Peron, 40 in Scotia, 200-500 in Queensland.

There are fewer than 1,000 individuals in the Northern Territory and 5,000-10,000 in non-reintroduced Western Australia. The global population might be under 10,000 individuals. The species is wide-ranging and patchily distributed. The population estimates of bilbies in the Northern Territory and Western Australia are very approximate, as there are no published numbers in peer-reviewed journals. It is known from aerial surveys that bilby signs (diggings) in the areas where bilbies are persistent occur less than 15 to 20 km apart.

“TEN THOUSAND INDIVIDUALS REMAINING”

Image: Bilby, Australia. Photographer unknown.

Bilby populations are not known to be seriously fragmented, and from what I am aware the species is protected under CITES APPENDIX I (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of wild Fauna and Flora).

“WHAT’S WITH THE LARGE EARS?”

You’ll find that many small and even large animals that live within extremely arid and hot countries, and are active during the daytime will host large fan like ears. Without these large cooling like rabbit ears many species of animals wouldn’t be able to radiate heat away from its most important organs - being the brain. Smaller ears would most certainly result in the mammal dying from massive heat stroke, and dehydration. However due to the lack of research on the bilby, we still don’t know for sure if these massive ears do indeed help keep the species cool.

Bilby ears are almost naked, which ‘may be for temperature regulation’, but because the research hasn’t been done we don’t actually know for sure. One thing that scientists studying bilbies do agree on is the variability in behavior between bilby populations living in different conditions around Australia. They’ve adopted different diets, burrows, breeding habits and social networks, and this adaptability has been the key to their survival.

THREATS

The current bilby distribution is associated with a low abundance or absence of foxes, rabbits, and livestock. Major threats relate to predation from foxes, habitat destruction from introduced herbivores, and changed fire regimes. Predation pressures “from feral cats” and dingoes occurring in association with pastoral practices may be a threat to the bilby. Feral cats have affected the success of reintroduced populations. Additional threats to the bilby include mining and other development, and road mortality.

BILBY FACTS

When: Bilbies are opportunistic breeders waiting until conditions are good, rather than particular seasons.

Where: In the wild, bilbies are now limited to patches of the northern desert areas of NT and WA. and a tiny isolated remnant population in SW QLD. They are also found in sanctuaries and breeding colonies in WA, NSW, SA and QLD.

Other info: The name bilby comes from the Yuwaalaraay people of northern NSW. They are important in Aboriginal culture and were a common food resource. Bilbies live up to 7 years in the wild and 11 years in captivity. They are considered endangered.

WHAT DO BILBIES EAT?

Bilbies are omnivores and eat insects, seeds, bulbs, fruit and fungi. Most food is found by digging in the soil. Big ears quickly detect insect prey, which they catch with their long tongue.

Thank you for reading.

Every Monday and Friday I.A.R.F publishes in the last (6 months of each year) an Endangered Species Post. Furthermore every Wednesday I.A.R.F also publishes investigative articles relating to wildlife, environmental and animal concerns. For more information please subscribe to our news feed for free here www.speakupforthevoiceless.org

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M. Environmental & Human Science.

Endangered Species Monday: Bombus occidentalis |Extinction is Imminent.

Endangered Species Monday: Bombus occidentalis

“1/3 bites of food we eat comes from a plant that was pollinated by a bee”

What are we humans doing to Planet Earth?, We are destroying so many pollinating animals, that soon they’ll be none left. When or if that day occurs, when there are no more pollinators, we ourselves will be fighting to stay alive, can you imagine that? Human extinction is slowly in the making… …No matter how many vegans or vegetarians there are, we all require plants. No plants = No life!

That’s a Scientific Fact of Life!

Dr Jose Depre

This Monday’s Endangered Species Post (E.S.P) I document on the Western Bumble Bee. Scientifically identified as Bombus occidentalis this particular species of bee is listed as (vulnerable), and is now nearing complete extinction within the wild, despite conservation efforts aimed at reducing dangers, things certainly are not looking good for the bee, or crops the species pollinates either. Image credits: Rich Hatfield

The species was identified back in 1858 by Dr Edward Lee Greene, Ph.D, (August 10, 1843 – November 10, 1915) was an American botanist known for his numerous publications including the two-part Landmarks of Botanical History and the naming or redescribing of over 4,400 species of plants in the American West.

Endemic to: Canada (Alberta, British Columbia, Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, Yukon); United States (Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). To date we still don’t know what the “exact current rate of decline is”, or even if the Western Bumble Bee is going to be with us within the next decade. Its ‘likely that based on current surveys the species will be extinct within the next 10 years (max)”.

Since 2008-2014 there has been quite a significant rate of decline st 11%-12%, sparking concerns that the Western Bumble Bee ‘may eventually be listed as critically endangered’ within the United States and Canada. Scientists confirmed that in one area which is [unknown], possibly the United States via field surveys the species was not found during the years of 2003-2007 (which is of course quite concerning), especially when the species is a major pollinator, and has been seen only in very low numbers at (one to seven per year) each year from 2008 to 2014.

A study conducted focusing on ‘range decline’ relating to some eight separate species native to the United States, showed that the Western Bumble Bee species alone had decreased in population size within its (range), by some 28% (EST) between the years of 2007-2008. A further study conducted by conservation scientists concluded that by 2007-2009 surveys detected the species only throughout the Intermountain West and Rocky Mountains; it was largely absent from the western portion of its range.

Further declines have been reported within the [US] states’ of Oregon and Washington, however populations seem to be somewhat stable within (northeastern Oregon). Populations are also to a degree stable within Alaska and the Yukon. Average decline for this species was calculated by averaging the change in abundance, persistence, and EOO.

- Current range size is estimated to be at some 77.96%

- Persistence in current range relative to historic occupancy: 72.56%

- Current relative abundance relative to historic values: 28.51%

- Average decline: 40.32%

From viewing all data records I can confirm that the (exact rate of decline) within the species range, and its persistence total some 20%, with a 70% rate of decline in ‘abundance’. Surveys have also proven the this decades rate of decline is bar far lower than the last decades, which again raises some rather large concerns about a near future extinction occurring.

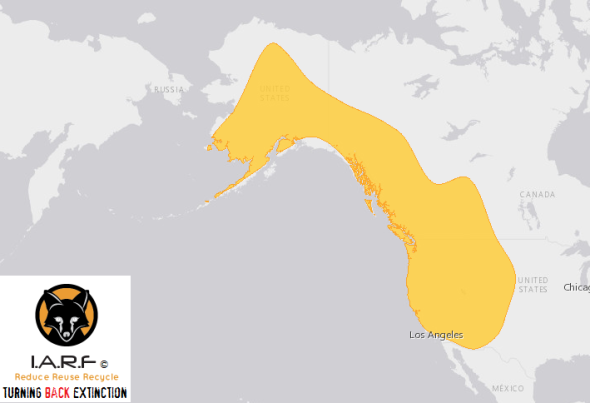

Image: Western Bumble Bees’ extant zones.

In the past, B. occidentalis was commercially reared for pollination of greenhouse tomatoes and other crops in North America. Commercial rearing of this species began in 1992, with two origins. Some colonies were produced in rearing facilities in California by a company which imported the technology for rearing bumble bees and applied it to rearing B. occidentalis locally in California.

This same year, a distributor for a competitor which did not have rearing facilities in North America at the time was granted permits by the US Department of Agriculture – Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA-APHIS) for a three year window of time (1992-1994) to export queens of B. occidentalis and B. impatiens to European rearing facilities for colony production.

Following rearing, these colonies were then shipped back to the U.S. for commercial pollination. In 1997, commercial producers began experiencing problems with disease (Nosema) in the production of B. occidentalis. Eventually, the availability of B. occidentalis became critically low, and western crop producers who had become dependent on pollination provided by this species began requesting that APHIS allow the shipment and use of B. impatiens in western states.

In 1998, the USDA-APHIS issued permits to allow B. impatiens to be used in the western U.S. However, within a few years, the USDA-APHIS stopped regulating the interstate movement of bumble bees altogether, citing their lack of regulatory authority. Bombus occidentalis is no longer bred and sold commercially and B. impatiens is used widely in the western U.S. One has to wonder though that since the the US Government stopped granting permits for Bombus occidentalis mostly due to species decline, primarily due to human ignorance, will the same rate of decline now be seen with the species B. impatiens?

Currently to date the only ‘known conservation actions that are under way is that of management, research and surveys’, meanwhile its likely that come the next decade we’ll have lost the species due to a lack of improving/increasing populations, and habitat while failing to decrease disease and virus.

THREATS

Populations of this declining species have been associated with higher levels of the microsporidian Nosema bombi and reduced genetic diversity relative to populations of co-occurring stable species. The major decline of the subgenus Bombus was first documented in B. occidentalis, as Nosema nearly wiped out commercial hives, leading to the cessation of commercial production of this species. Wild populations crashed simultaneously and the closely related B. franklini has been pushed to the brink of extinction.

However, Koch and Strange (2012) found high levels of infestation by Nosema in interior Alaska where this bumble bee was still quite common. In addition to disease, this species is faced with numerous other stressors including habitat loss and alteration due to agricultural intensification, urban development, conifer encroachment (resulting from fire suppression), grazing, logging and climate change.

Modifications to bumble bee habitat from over grazing by livestock can be particularly harmful to bumble bees by removing floral resources, especially during the mid-summer period when flowers may already be scarce. In addition, livestock may trample nesting and overwintering sites, or disrupt rodent populations, which can indirectly harm bumble bees. Indirect effects of logging (such as increased siltation in runoff) and recreation (such as off-road vehicle use) also have the potential to alter meadow ecosystems and disrupt B. occidentalis habitat.

Additional habitat alterations, such as conifer encroachment resulting from fire suppression, fire, agricultural intensification, urban development, and climate change may also threaten B. occidentalis. Insecticides, which are designed to kill insects directly, and herbicides, which can remove floral resources, both pose serious threats to bumble bees. Of particular concern are neonicotinoids, a class of systemic insecticides whose toxins are extraordinarily persistent, are expressed in the nectar and pollen of plants (and therefore are actively collected by bumble bees), and exert both lethal and sublethal effects on bumble bees.

Since B. occidentalis has recently undergone a dramatic decline in range and relative abundance, reduced genetic diversity and other genetic factors make this species especially vulnerable to extinction, and may lead to increased pathogen susceptibility. Recent research indicates that populations of B. occidentalis have lower genetic diversity compared to populations of co-occurring stable species.

It is therefore regrettable, that despite research, management and surveys - extinction is imminent, when though, we simply don’t know, however when it does happen, it means that yet another pollinator that we humans and animals depend on will be gone for good.

Image: Female B. occidentalis

Humans will never learn or understand just how critically important our wildlife is, until its gone. They’ll then be fighting over themselves, fighting to stay alive. By that time, human extinction will already be in the process.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Chief Environmental & Botanical Officer.

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

VEGAN MONDAY: CHERRY ALMOND QUINOA SMOOTHIE

CHERRY ALMOND QUINOA SMOOTHIE

Written by Dr Jose C. Depre | A great breakfast for all those on the go, healthy and nutritious, not forgetting packed with tons of energy, fiber, antioxidants and finally Mother Natures healing remedies.. Please follow our main vegan and vegetarian site hereto on > Facebook <

VEGAN MONDAY | VEGAN SOUTH AMERICA.

Keeping in line with our month long South American vegan and vegetarian delights we bring to you again #veganmonday. Every Monday and Friday we host a vegan or veggie recipe as we have done for over two years from around the world. This week we continue with our South American recipe guide.

We kind of laid off the vegan and veggie smoothies and focused more on main dinners, and where to locate them foods, and/or recipes. However today we have chosen a more South American smoothie breakfast recipe, and why not? EVERYONE needs a smoothie vegan or veggie of some-sort every day.

So, what we got for ya? Check this baby out.

CHERRY ALMOND QUINOA SMOOTHIE.

The recipe is quite simple, and the ingredients are very easy to obtain from your local hypermarket. Frozen or fresh cherries can be purchased in just about every good hyper-stall, and almonds are literally obtainable everywhere. You can mix this smoothie with any type of [non-dairy milk] you jolly well wish. Or if your not a vegan, I do ‘advise’ that you at least purchase your milk from sources where cows and their young are not killed, but live their life out naturally and happily.

Yes you can locate farms where cows and their young live naturally as I’ve lived on many of these natural farms, where hand milking is the only type of milking, and milk is only harvested when the cows are ready, and no, not a single animal is killed. Nope its not organic as a whole, more natural living, and 100% organic combined.

RECIPE - CHERRY ALMOND QUINOA SMOOTHIE:

You will require:

1. One cup of almond milk. I dislike almond milk so tend to go with coconut milk, and then incorporate blended almonds within the milk.

2. Half of a cup of pitted cherries (frozen are best), but that’s my choice not necessarily yours.

3. 1/4 of a cup of cooked quinoa.

4. You will then need 1 delicious tablespoon of almond butter.

5. One tablespoon of flax seeds (very good for you).

6. Finally 1 tablespoon of agave syrup.

If I am feeling unwell, or suffering a sore throat, or just require a little more natural sweetness then I’ll add 2 tablespoons of (bees honey). This honey comes from bees that build their nest within specially built hives that (drain the honey naturally), and DOES NOT require smoking of the bees or disturbance of the hive to obtain the honey.

YES there are hives that are now fitted with such mechanisms that don’t harm the bees. See below for one example:

Add all ingredients to a blender and pulse until the fruit is in small chunks. Increase the speed to medium-high and continue to blend until creamy and smooth.

Enjoy your breakfast.

Have a nice day

Dr Jose C. Depre.

Environmental & Botanical Scientist.

Endangered Species Friday: Dendrolagus dorianus | Cuddly Teddy Bear Facing Extinction.

Endangered Species Friday: Dendrolagus dorianus

This Friday’s (Endangered Species Post) [E.S.P] I touch up on this rather unusual species of tree kangaroo that’s rarely mentioned within the world of conservationism. Furthermore I also wish to set the record straight about these wonderful and utterly adorable species of mammals which many people seem to believe are endemic ‘just to Australia’. This particular species is actually native to Papua New Guinea, generically identified as Dendrolagus dorianus. (Image credits: Daniel Heuclin).

Listed as (vulnerable), the species was primarily identified by Dr Edward Pierson Ramsay (3 December 1842 – 16 December 1916). Dr Ramsay was an Australian zoologist who specialized in ornithology. Among organisms Dr Ramsay named are the pig-nosed turtle, giant bandicoot, grey-headed robin and Papuan king parrot.

D. dorianus lives within a country of immense cultural and biological diversity. A country known for its beaches, coral reefs and scuba diving. Not forgetting the countries inland active volcanoes. Locals commonly identify the animal as the; Doria’s tree kangaroo or the unicolored tree kangaroo. Doria’s tree kangaroo is within the order of Diprotodontia, and the family identified as Macropodidae.

Since 1982 to 1994 the species has remained at [vulnerable level] of which back in 1996 a further assessment of the species noted a possible population decline. The decline prompted environmentalists to notch the species further up the list of [vulnerable species]. However a survey in 2008 concluded the species hadn’t as yet qualified for any further threatened status (E.g) endangered (which would unfortunately be the next listing should threats not decline in the wild).

Scientific research and population evaluations have shown a staggering 30% decline of overall wild populations which is quite a large population decrease, although “allegedly not concerning enough as yet to reclassify this particular specimen as endangered”. Yes its unfortunate that the current news relating to (decreasing populations), is indeed factual, and its likely (as explained), that should threats in the wild not decrease anytime soon, we could see a new extinction occurring in as little as ten years “if not sooner”. Populations are not known to be ‘fragmented’.

Image: Rare glimpse of the Doria Tree Kangaroo.

Identified in 1883 there are very few conservation actions actually known that could help increase declining population sizes which I myself find somewhat frustrating, not to mention perplexing, especially when one takes into consideration the current level of threats associated with this specie in Papua New Guinea.

Research proves the species inhabits some several protected national parks [NP’s], unfortunately extreme hunting activities I.e illegal poaching is still ongoing. While Anti Poaching Operations [APU’s] do exist, the fact of the matter is that Cites (The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species Wild Flora and Fauna), still hasn’t listed the species as (protected or endangered) on either Appendix I or Appendix II.

Image: Extinction may occur in a decade of not sooner.

To date the current population level is unknown, furthermore reproduction is also believed to be incredibly low and poor.

MAJOR THREATS

Known threats relate to the bush meat trade, which if not controlled will unfortunately push the species into extinction. Hunting with dogs, unregulated/illegal hunting is quite high and problematic within the region. Finally the species absolutely hates canines of which when threatened emits depressed vocalizations. Future threats have been identified as habitat loss and degradation.

The Doria’s tree kangaroo lives at elevations of some 600-3,650 meters of which is mostly nocturnal and a solitary animal. Dr Ramsay named the species after Professor Marquis Giacomo Doria (1 November 1840 – 19 September 1913) whom was an Italian naturalist, botanist, herpetologist, and politician of Italy.

Doria’s tree kangaroo is probably one of the largest species of tree kangaroos on the planet, although this is somewhat debatable. Weighing in at 6.5-14.5 kilograms, length is around 60-80 centimeters, with a tail length of some 40-70 centimeters. With a large tail, dense black and brown fur, large powerful claws and stocky build, the appearance of this specific animal almost appears to look like a medium sized bear.

Diet consists of leaves, flowers, fruits and buds, there is no evidence that suggests or points to any form of meat eating either. Gestation period of females is around thirty days, of which the ‘single young baby’ will remain in mothers pouch for around ten months.

There really is limited information about this specific species which could be due to the fact the species is actually very rare, nocturnal, and lives at moderate to high elevations within dense montane forests. I am asking the public to please share this article far and wide to help us push more awareness of this species into the public domain, which we hope will encourage (Cites) to protect the species sooner rather than later.

This article is dedicated to Ms Toni Devine, a wonderful young lady that absolutely adores these wonderful species of animals, who wouldn’t adore them, they are truly remarkable, intelligent, and in way more like cuddly teddy bears.

Chief Environmental & Botanical Officer

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental Crimes Investigator

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Follow us on Facebook via clicking the link below:

https://www.facebook.com/InternationalAnimalRescueFoundationAfrica/

Endangered Species Friday: Aquila nipalensis | Wind Farms Pushing Steppe Eagle into Extinction?

Endangered Species Friday: Aquila nipalensis

This Fridays (ESP) - Endangered Species Post is dedicated to the A. nipalensis, commonly known as the Steppe Eagle, identified back in 1833. Image credit: Kartik Patel

The Steppe Eagle was formally identified by Dr Brian Houghton Hodgson (1 February 1800 or more likely 1801 – 23 May 1894) was a pioneer naturalist and ethnologist working in India and Nepal where he was a British Resident. He described numerous species of birds and mammals from the Himalayas, and several birds were named after him by others such as Edward Blyth.

Dr Brian H. Hodgson was a scholar of Tibetan Buddhism and wrote extensively on a range of topics relating to linguistics and religion. He was an opponent of the British proposal to introduce English as the official medium of instruction in Indian schools. Had Dr H. Hodgson not introduced English into the many Indian schools, its very likely very few Indian citizens would today know how to speak the English language.

A. nipalensis is listed as (endangered), although its likely the predatory eagle will soon be relisted as (critically endangered), should conservation efforts not improve the current status of this remarkable bird of prey, however this particular bird is somewhat of a mystery.

The major reason why this species is listed as (endangered) which was only recently, is primarily due to wind farming of which birds are reported to fly directly into large structural turbines, which unfortunately, results in their death, or serious injury. Birds that are rescued suffering serious trauma are rarely released back into the wild, or make a full recovery.

From 1988 to 2000 the species was listed as (lower risk). Then from 2003 to 2014 the species remained at (least concern). A risk assessment conducted last year (2015), concluded that the species qualified for (endangered status). Which is somewhat concerning. To date we know the species has already been pushed into regional extinction in the countries identified as; Moldova and Romania. Today the species still remains endemic within the following countries;

Afghanistan; Albania; Armenia; Azerbaijan; Bahrain; Bangladesh; Bhutan; Botswana; Bulgaria; China; Congo; Djibouti; Egypt; Eritrea; Ethiopia; Georgia; Greece; India; Iran, Islamic Republic of; Iraq; Israel; Jordan; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kuwait; Kyrgyzstan; Lebanon; Malawi; Malaysia; Mongolia; Myanmar; Namibia; Nepal; Oman; Pakistan; Palestinian Territory, Occupied; Qatar; Russian Federation; Rwanda; Saudi Arabia; Singapore; South Africa; South Sudan; Sudan; Swaziland; Syrian Arab Republic; Tajikistan; Tanzania, United Republic of; Thailand; Turkey; Turkmenistan; Uganda; Ukraine; United Arab Emirates; Uzbekistan; Viet Nam; Yemen; Zambia and finally Zimbabwe.

Aquila nipalensis is also a vagrant visitor to most of Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, South East Asia, Southern and Eastern Africa, ranging from Spain; Norway; France; Germany; Finland, Korea; Somalia; Slovakia Etc. Continued rate of decline is (unknown), which is concerning bird lovers and conservationists. Data recorded from the last assessment back in (2015), stated that populations are declining very rapidly.

Population Uncertainty

There seems to have been some perplexing information from the last assessment (before 2015’s) relating to population trend conducted we believe in (2010 or 2012). However the (2015) assessment has confirmed that the current population trend may stand at some: 100,000-499,999 (which is an estimate band or population band). Populations are not known to be (seriously fragmented). Surveys conducted back in (2001) placed the number of pairs at ‘80,000 pairs or 160,000 mature individuals’. Unfortunately the (European population) is estimated to be standing at 800-1,200 pairs in total.

Bird-Life International (2015) estimated that Europe holds the lowest population density standing at some 9%. So a very preliminary estimate of the global population size is 17,800-26,700 mature individuals. A further assessment back in (2001) relating to the European trend stated “160,000 mature individuals was much lower than previously believed”. So as one can see ‘population uncertainty’ is the second likely reason why the species has been re-listed as (endangered). Not forgetting being rather confusing at times too.

Latest Population Assessment Estimate

The latest, and most current population assessment estimate states numbers range (in total) at 31,372 (26,014-36,731) which equates to 62,744 (52,028-73,462) mature individuals or 94,116 (78,042-110,193) individuals. The population is placed in the band 100,000 to 499,999 mature individuals. It must be noted that 100,000 to 499,999 is not the true population count, but more the ‘band that the species currently stands at/qualifies for’.

Habitat destruction, agriculture, conversion of Steppe Eagle land for farming, persecutions, but most worrying is wind-farming that is “seriously threatening the species as we know it today”. Collisions with wind-turbines is quite a serious concern as the Steppe Eagle is not exactly a small bird, and when hunting, especially within converted land that hosts wind farms, Steppe Eagles are either killed or seriously injured to the point that they can never be rehabilitated back to the wild. Night collisions are reported more than day collisions.

Image: White tailed Eagle killed after colliding with a wind farm in the background.

The image above depicts a White Tailed Eagle that was located dead after a suspected collision with a wind turbine. As one can clearly see these Eagles are not small, nor are wind turbines. Unfortunately birds come off the worst as we humans crave more and more greener energy. The only real reasonable solution here would be to now lobby governments and industries to build wind farms away from ‘all bird habitat’, or at sea. Unfortunately, again this is easier said than done. While at sea wind turbines are being blamed for whale beaching’s due to turbine vibrations, meanwhile birds are mostly, sadly dying when hitting these gigantic steel/carbon structure’s.

Steppe Eagles migrate, and are said to be closely related to the subspecies Aquila rapax. Steppe Eagles are around 25-31 inches in length, with a mean wingspan of 5.1-7.1 feet. Females weigh 5-10 lbs, while males weigh in at around 4.4 to 7.7 lbs. Steppe Eagles are said to breed mainly from Romania of which the species is currently (regionally extinct) within the country. Further evaluation of breeding behavior states the species breeds in Central Asia, Mongolia to Africa, with further breeding occurring within Eastern Europe. Females lay on average 1-3 eggs within a clutch.

Image: Credited: Peter Romanow (Germany).

Major Threats

Listed on the (Convention of International trade in Endangered Species wild flora and fauna - Cites), Cites Appendix II. Threats are listed below for your information.

The species has declined in the west of its breeding range, including extirpation from Romania, Moldova and Ukraine, as a result of the conversion of steppes to agricultural land combined with direct persecution. It is also adversely affected by power lines and is very highly vulnerable to the impacts of potential wind energy developments. It was recently found to be the raptor most frequently electrocuted by power lines in a study in western Kazakhstan. When one views the sheer size of these massive birds of prey, one can clearly envisage just how easy they can fall prey to hitting these massive carbon wind structures, and power lines,

Young eagles are taken out of the nest in order to sell them to western European countries. A decline in the number of birds and a reduction in the proportion of juveniles migrating over Eilat, Israel began immediately after the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986, leading Yosef and Fornadari (2004) to suggest that the species may have been affected by radioactive contamination. This species is vulnerable to the veterinary drug Diclofenac too. Read more here on Chernobyl.

CONCERNING DATA ON CHERNOBYL AND LOW BIRD SPERM RATE: https://www.audubon.org/news/chernobyls-radiation-seems-be-robbing-birds-their-sperm

Wind Farming | Eagles

Wind energy is the fastest growing source of power worldwide according to the World Bank. China plans a 60% increase in the next three years and the US a six-fold jump by 2030. The EU aims to produce 20% of its energy through renewables by 2020 - much of this is from wind. Will this huge expansion of wind farms have a serious impact on bird life? It looks likely, especially where birds habitat is being encroached onto by such developments.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) estimates that 440,000 birds are killed in collisions with wind turbines each year; without stronger regulation, says the American Bird Conservancy (ABC), the annual toll will exceed one million by 2030. To address this issue, the U.S. Department of the Interior has released voluntary guidelines to help developers minimize the impact of wind energy projects on bird habitat and migration. Developed over five years with an advisory committee that included government agencies, the wind energy industry, and some conservation organizations, the guidelines are intended to ensure compliance with federal laws such as the Endangered Species Act—although the rules allowing them to do so are controversial.

Read more here: http://hqinfo.blogspot.co.uk/2012/11/bird-collision-deaths-wind-farms.html

Image: Red Kite killed found dead after colliding with a wind-turbine.

There are reasons why birds are likely to be affected by wind farms. Wind developments tend to be placed in upland areas with strong wind currents that have a lot of potential to generate energy. Birds – particularly raptors like eagles or vultures – use these currents as highways – and so are likely to come into contact with the turbines. It’s not just the turbine blades that pose a risk to birds; research indicates that wind developments can disrupt migration routes. What’s more, foraging and nesting habitat can also be lost when turbines are put up.

Despite these concerns, the current body of research suggests wind farms have not significantly reduced bird populations. Several studies suggest birds have the ability to detect wind turbines in time and change their flight path early enough to avoid them. And one small study found no evidence for sustained decline in two upland bird species on a wind farm site after it had been operating for three years. Another found that wild geese are able to avoid offshore wind turbines. (Geese though fly at daytime, and are not predatory day and nighttime carnivorousness hunters).

A large peer-reviewed study in the Journal of Ecology monitored data for ten different bird species across 18 wind farm sites in the UK. It found that two of them- curlew and snipe – saw a drop in population during the construction phase, which did not recover afterwards. But the population of the other eight species were restored once the wind farms were built.

Read more here: http://www.carbonbrief.org/bird-death-and-wind-turbines-a-look-at-the-evidence

The current fate relating to the Steppe Eagle is somewhat worrying. Agriculture, persecution, young theft for trade, and wind - turbine farming is all but concerning plundering the species into further threatened status. After reading many studies dating back to 2012 regarding wind turbines, and whether they were indeed responsible for bird deaths, 2012 evidence didn’t really show much to prove that birds were affected. However after reading the ‘damning evidence relating to the Steppe Eagle’, its without a doubt that wind farms are most certainly ‘impacting on this species and others’ locally and internationally. The question is how do we deal with this problem?

We need wind to generate more greener energy thus decreasing our carbon emissions. Furthermore we also need birds of prey to control rodent, insect, and general pest control. Large birds of prey are also very useful within Anti Poaching operations, and act as the eyes and ears for both farmers and anti poachers. While there is no evidence to prove my own suspicions here, I do believe that certain bodies within government are being forced to ignore ongoing issues with wind farms and bird collisions. The excuse that birds can quickly change course is indeed factual to some degree, well, only if the bird is flying during daytime hours. Unfortunately most birds of prey also fly and hunt at night. So how is one supposed to change their course (at nighttime when unable to see the turbine in time)?

Please view the videos below for more information.

BIRD OF PREY | TURBINE COLLISIONS

STEPPE EAGLE

Thank you for reading, please share and help create more noise about this subject before time runs out.

Dr Jose. C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical and Human Science

Endangered Species Monday: Hylonympha macrocerca

Endangered Species Monday: Hylonympha macrocerca

This Monday’s Endangered Species Post (ESP) watch I take a rare glimpse into the life of Hylonympha macrocerca, commonly known as the Scissor Tailed Hummingbird. Identified in 1873 by Dr John Gould FRS September 1804 – 3 February 1881) whom was an English ornithologist and bird artist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates that he produced with the assistance of his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists including Edward Lear, Henry Constantine Richter, Joseph Wolf and William Matthew Hart. He has been considered the father of bird study in Australia and the Gould League in Australia is named after him. His identification of the birds now nicknamed “Darwin’s finches” played a role in the inception of Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. (Image: Scissor Tailed Hummingbird)

Listed as (endangered) this remarkable specimen was listed as threatened back in 1988. Since this time little conservation efforts have been seen to improve the species overall status within the wild of which extinction is incredibly likely. From 1994 to 1996 the species was listed as critically endangered. From the start of the Millennium conservation efforts did improve the wild status of the hummingbird to (vulnerable), unfortunately from 2008 to date the species has been re-listed as endangered again. From my own evaluations of the birds current threats and shrinking habitat, extinction will occur within the next five to ten years, unless conservation efforts improve, funding increases and dangers disperse soon.

Endemic to Venezuela and Bolivia evidence has shown that overall population sizes are decreasing very rapidly. The population trend when last evaluated back in 2012, showed around 10,000 to 19,900 ‘individuals’ within the wild. This equates to exactly 6,000 to 13,000 ‘mature individuals’ remaining, which is rounded to 6,000 to 15,000 ‘birds in total’. The Scissor Tailed Hummingbird specie inhabits lower and upper montane humid forest, where it has been recorded at 800-1,200 m on Cerro Humo, and 530-920 m further east.

In primary forest, the specie feeds mainly at bromeliad flowers and on their insect inhabitants, whereas in secondary forest, feeding is associated with the shrubs Heliconia aurea and Costus sp. Although it is regularly seen feeding on Heliconia in open areas it may nevertheless be dependent on the availability of pristine forest nearby. It also hawks insects from exposed perches. There may be seasonal movements.

Major Threats

Listed on Cites Appendix II (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species wild flora and fauna), increases in cash-crop agriculture, especially the cultivation of “ocumo blanco” (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) and “ocumo chino” (Colocasia esculenta), since the mid- to late 1980s have resulted in some uncontrolled burning and forest degradation. Cerros Humo and Patao have been worst affected, with the east of the peninsula fairly undisturbed.

Since it is an understorey inhabitant, removal of understorey vegetation for coffee and cacao cultivation is likely to lead to reduced population density. It is considered nationally Endangered in Venezuela, and has been recognized as a “high priority” species, amongst the top dozen priorities for bird conservation in Venezuela.

Image: Scissor Tailed Hummingbird.

Occasionally the species is misidentified as the Red-billed streamertail which is also commonly known as the scissor-tail or scissors tail hummingbird. However its fairly easy to distinguish between the two when viewing online or within books. This particular species (in question) is not native to Jamaica, and one can quite easily differentiate between the two. The Scissor Tailed Hummingbird has obviously acquired its name due to its unique scissor tailed rump feathers, whereas the Jamaican Red-billed streamertail doesn’t host the same features but more as explained - streamer like rump feathers.

Sadly as explained due to increasing threats we will lose this bird unless conservation efforts improve dramatically and dangers subside. However this is unlikely to occur. The Scissor Tailed Hummingbird will be yet another species of bird added soon to the extinction list of amazing birds, that we humans have destroyed. The video below depicts a female Scissor Tailed Hummingbird within the Venezuela wild.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre.

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.