Endangered Species Monday: Archaius tigris

Endangered Species Monday: Archaius tigris

This Mondays Endangered Species watch Post (ESP) I document on yet another African species of wildlife that hunting revenue is not helping to preserve. The Tiger Chameleon was identified back in 1820 by Dr Heinrich Kuhl (September 17, 1797 – September 14, 1821) was a German naturalist and zoologist. Kuhl was born in Hanau. He became assistant to Coenraad Jacob Temminck at the Leiden Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie. (Image: Credited to Henrick Bringsoe, A tigris).

In 1817 he published a monograph on bats, and in 1819 he published a survey of the parrots, Conspectus psittacorum. He also published the first monograph on the petrels, and a list of all the birds illustrated in Daubenton’s Planches Enluminées and with his friend Johan Coenraad van Hasselt (1797–1823) Beiträge zur Zoologie und vergleichenden Anatomie (“Contributions to Zoology and Comparative Anatomy”) that were published at Frankfurt-am-Main, 1820.

Commonly known as the Tiger Chameleon or Seychelles Tiger Chameleon the species is currently listed as [endangered] which is not uncommon as like many Chameleons within the Seychelles their range is shrinking by the year or being overrun by invasive botanical species.

Endemic to the Seychelles the species has been listed as endangered since 2006 of which populations trends are unknown. Much documentation often cites the species at “comparatively” low density, however one must not take this as factual until a true population count is seen. It has been alleged that for every [five hectares] there is possibly 2.07 individuals which isn’t good ‘if true’ since the island is only 455 km2.

From what we know the species remains undisturbed where there aren’t invasive Cinnamon trees identified as the Cinnamomum verum. However where C. verum is spreading the Tiger Chameleons habitat is under threat from this invasive plant. There is a negative correlation between Chameleon density and the presence of cinnamon, suggesting this invasion is detrimental to chameleon populations. Negative correlation is a relationship between two variables such that as the value of one variable increases, the other decreases.

The Tiger Chameleon’s main endemic range on the Seychelles islands is Mahé, Silhouette and Praslin. A historical record from Zanzibar (Tanzania) is erroneous. It occurs from sea level to 550 m asl, in areas of the islands that have either primary or secondary forest, or in the transformed landscape if there are trees and bushes present. Although they are currently estimated to have a restricted distribution on each island (following survey transects conducted by Dr Gerlach if anecdotal observations from transformed landscapes (e.g. degraded areas outside the areas surveyed) are valid, then the distribution would be larger than mapped at present.

To date the only [non-active] conservation actions that I am aware of are within the Vallee de Mai on Praslin which is currently not a protected national park. Fortunately the species is protected to some degree in the Morne Seychelles, Praslin and Silhouette National Parks. The primary threat within non-protected areas is as explained invasive Cinnamon which seems to be posing similar threats to both small reptilians, insects and birds on the islands and mainland Madagascar.

While the species has been in the past used as a trade animal it was alleged that there were no Cites quotes since 2000 - 2014. However from 1997 - 2013 a total of twelve live specimens were legally exported [despite the species threatened at risk status]. Cites allowed the twelve species to be exported for use within the pet trade which I myself find somewhat confusing. Two specimens were exported to Germany in 1981 with the remainder [10] sent to Spain. I am a little perplexed as to why these twelve specimens were legally exported, furthermore I have found no evidence or follow up data that would satisfy me in believing this export was even worthwhile for the species currently losing ground within their natural habitat.

From 1981 -2010 a further 98 dead specimens were legally exported for scientific zoological projects. Then in 1982 a single live specimen was legally exported with Cites permit for experimental purposes. While I cannot [again] locate any evidence or reason as to why this single specimen was exported alive - I must make it clear that Cites is sympathetic to Huntington Life Science’s and various other animal experimental laboratories. However this doesn’t prove that Cites has exported to anyone of these experimental research centers, it is merely my assumption.

Image: Archaius tigris

No other trade is reported out of the Seychelles, although re-export of specimens imported to Germany and Spain has been reported to Switzerland and South Africa, respectively (UNEP-WCMC 2014). This species is present and available in limited quantities in the European pet trade, and illegal trade and/or harvest may occur on a limited basis. ‘A’ report handed to myself from an [anonymous 2014] officer from the office of UNEP states that a population of some 2,000 specimens has been recorded [2014] however there is yet again no census historical data to back these claims/report up. I again must point out that if its proven there are no fewer than [2,000 Tiger Chameleons] remaining in the wild and, Cites is allowing export then Cites is going to come under immense pressure from International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa because exporting live animals for pet trade at such ‘alleged’ depressed populations - is neither helping the species nor supportive of conservation practices.

Threats

The main threat is habitat degradation as a result of the invasion by alien plants species, especially Cinnamomum verum, principally on Mahé and Praslin. Cinnamon is displacing other vegetation, it is present all over the islands and it is the fastest growing, heaviest seeding plant in most areas and is changing the composition of the forests. Currently it makes up 70-90% of trees in Seychelles forests, reaching >95% in some areas. For Archaius tigris, the cinnamon trees provide a normal structure of vegetation, but the invaded forests support a massively diminished insect population, somewhere in the region of 1% of normal abundance. This excludes invasive ants which are the only common invertebrates associated with cinnamon.

In addition, the cinnamon produces a denser canopy than native trees, giving deeper shade which excludes forest floor undergrowth (other than cinnamon seedlings), and this also is a factor in the reduced insect abundance. The Chameleons are found on cinnamon and in cinnamon invaded areas, as long as there is a wide diversity of other plants and a dense undergrowth. In fact, rural gardens can provide habitat for the Chameleons, because these tend to be more diversity in terms of flora, and therefore can support invertebrate fauna.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Endangered Species Monday: Afrithelphusa monodosa.

Endangered Species Monday: Afrithelphusa monodosa

Warning: Extinction is now Inevitable

This Mondays (E.S.P) -Endangered Species watch Post I focus on a species of fresh water crab that’s rarely spoken about within the theater of conservation, or animal rights forums. Identified by Mr Bott from which I know little on and about this particular species of marsh crab is currently listed as endangered. Rarely do I document on a species of animal that I and other conservationists know will be extinct within the next five years. My aim for this Monday’s endangered species column is to raise awareness about the plight of this little creature, in a way I hope will force Cites and the Guinea government to now implement emergency evasive action to halt extinction immediately. (Image: Purple Marsh Crab, photographer unknown)

I must also point out that one must not confuse the [common name] of this species [above], identified back in 1959, to that of the United States [Purple Marsh Crab]. Professor Linnaeus created the nomenclature system for a reason, and yet again I am seeing two species of animals that hold the same common names being confused with one-another. Sesarma reticulatum is not under any circumstances related to the Afrithelphusa monodosa pictured above and below.

Endemic to Guinea the species was listed back in 1996 as [critically endangered]. However since the last census was conducted back in [2007] the Purple Marsh Crab has since been submitted into the category of [endangered]. Unfortunately as yet there remains no current documentation on population size, furthermore from the 1996 census, marine conservation reports suggest that no fewer than twenty specimens have been collected from the wild. To date the ‘estimated’ population size stands at a mere 2.500 mature individuals.

Back in 1959 Mr Bott identified the specimen as Globonautes monodosus however from 1999 the species was re-named as Afrithelphusa monodosa. The Purple Marsh Crab is one of only five species in the two genera of which belong to a very rare group of fresh water crabs that are still endemic to the Guinea forests within the block of Western Africa. All five specimens within the two genera are listed as either [endangered or critically endangered], and as such its quite likely that all five specimens will become extinct within the next five to eight years, or possibly even sooner. It is without a doubt that one of the next species on the planet to go extinct will be the Purple Marsh Crab.

Allegedly new specimens have been discovered since [1996] however these reports are somewhat sketchy. When I last documented on the specimen back in 2010 there were no conservation efforts or any projects in the planning process that would help preserve the crabs future survival. We are now in 2015 and I have yet to witness any conservation projects planned or taking place, which I find rather frustrating. As explained the species will be extinct within a matter of years of which the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (Cites) should be protecting.

A. monodosa lives within the Guinea swamps and all year round wetland habitat within the northwestern Guinea. The original vegetation cover found at the farmland near the village of Sarabaya where this species was recently collected lies in southern guinea savannah in the semi-deciduous moist forest zone. Specimens of A. monodosus were collected from cultivated land from burrows dug into permanently moist soil each with a shallow pool of water at the bottom. At the end of the dry season after a six-month period without rain the soil in this area nevertheless remains wet year round, so this locality either has an underground water table close to the surface, or a nearby spring. The natural habitat of A. monodosus is still unknown but presumably this cultivated land was originally a permanent freshwater marsh.

There were no nearby sources of surface water and it is clear that these crabs do not need to be immersed in water (as do their relatives that live in streams and rivers), and that A. monodosus can meet its water requirements (such as keeping its respiratory membranes moist and osmoregulation of body fluids) with the small amount of muddy water that collects at the bottom of their burrow. This species is clearly a competent air-breather and has a pair of well-developed pseudol.

Image: Credited to Piotr Naskrecki. Purple Marsh Crab.

Current threats

To be truthfully honest I feel documenting on the current threats is in reality a waste of my time because both the Guinea government and Cites have known of these threats for many years. Yet little if any actions are being taken to suppress these threats. Either way I will document on them in the hope that someone will push for protection or whip into action a protective project sooner rather than later.

To date the species hasn’t been listed on either Cites (I-II) Appendix’s, the major present and future threats to this species include habitat loss/degradation (human induced) due to human population increases, deforestation, and associated increased agriculture in northwest Guinea.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa propose the following actions to be undertaken immediately:

- Up to date assessment of population size and location of any new and old habitats documented.

- Surveys to asses diets, predators, diseases and behavior.

- Investigations to locate new subspecies.

- Protection zones established within the highest populated zones.

- Liaising the Guinea government for funding of conservation projects.

- Listing of the species in (I Appendix) Cites.

- Community education and awareness programs.

- Removal of healthy and gene strong species for captive breeding programs.

Crabs Role within the Eco-System

Crabs are one of the major decomposes in the naval environment. In other terms, Crabs help in cleaning up the bottom of the sea and rivers by collecting decaying plant and animal substance. Many fish, birds and sea mammals rely on crabs for a food source. Regardless of if this is one species with low individual populations or not, extinction will only harm other animals. Furthermore will reduce other species food sources. The video below depicts the [Marsh Crabs] and their normal natural environment. The species in question which is identical to the Guinea Purple Marsh Crab is not included within the video but is related to the five genera.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Endangered Species Friday: Aceros nipalensis

Endangered Species Friday: Aceros nipalensis

This Fridays (ESP) - Endangered Species watch Post I have chosen to document on this stunning species known commonly as the Rufous-cheeked Hornbill, because of large population declines throughout most of the birds historical range. More awareness needs to be created with regards to this particular bird specie due to their natural habitat declining and localized extinctions that have already occurred in the past decade. Furthermore extinctions are now likely to occur within Viet Nam and [west] Thiland where hunting is the primary threat to the species.. (Image credit Ian Fulton).

Identified back in 1829 by Mr Brian Houghton Hodgson (1 February 1800 or more likely 1801– 23 May 1894) was a pioneer naturalist and ethnologist working in India and Nepal where he was a British Resident. He described numerous species of birds and mammals from the Himalayas, and several birds were named after him by others such as Edward Blyth.

Listed as vulnerable the A. nipalensis is endemic to Bhutan; China; India; Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Myanmar; Thailand and Viet Nam. Unfortunately A. nipalensis has already been declared extinct locally in Nepal. Like many large birds within this region of Asia the Rufous-cheeked (or necked) Hornbill’s populations are declining quite extensively throughout their range of which deforestation and habitat degradation and, hunting is primarily to blame.

The species has been listed on Cites Appendix (I-II) of which an estimated population census count has determined there are no less than 2,500 birds but no greater than 9,999. A survey count back in 2001 by Bird-Life International concluded that from the [estimate] above the [true] population count is actually by far more lower than previously suggested, however few conservationists are now debating this due to the birds ‘alleged’ extensive range within South East Asia.

From the Bird Life International (2001) census the organisation stated there was no fewer than 1,667 mature individuals but no greater than 6,666, which is rounded to 1,500 to 7,000 mature individuals exactly. Since the last 2001 census its quite possible populations have increased and decreased to date.

A. nipalensis is known to inhabit the following ranges; Bhutan, north-east India, Myanmar, southern Yunnan and south-east Tibet, China, [west] Thailand, Laos and Viet Nam. The species has declined [drastically] and is no longer common throughout most of its known historical range. While we know the species is now regionally extinct within Nepal the next likely localized extinction may very well be within Viet Nam of which its populations have fallen to alarming rates.

Within [most] of Thailand where the species was quite common reports have sadly indicated the bird is no longer commonly seen, and like Viet Nam, Thailand could become the third county to see localized extinctions occurring too, the only known habitat within Thailand that A nipalensis occurs now is within west Thailand. To date reports have confirmed that within Bhutan A. nipalensis remains pretty much common of which Bhutan is known to the birds [largest] stronghold.

Healthy large populations have also been documented back in 2007 within Namdapha National Park, India, Nakai-Nam Theun National Biodiversity Conservation Area, central Laos and perhaps also Huai Kha Khaeng, [west Thailand], and Xishuangbanna Nature Reserve, China. Some conservationists have been led to believe that while populations are considered quite large within these strongholds that the species may very well be “more widespread than previously thought”. Meanwhile the species is known to inhabit north Myanmar, and there are recent records from West Bengal and Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh, India.

Rufous-cheeked Hornbill commonly resides within broad-leaved forest, some reports have also indicated the species to be present within dry woodland too. Mating and nesting normally occurs from the months of March to June within large wide girth trees, the very trees that the species depends on though are being felled throughout most of the Hornbills historical range.

Image: Rufous-necked-Hornbill (Photographer unknown)

Major Threats

Its dependence on large trees for feeding and nesting makes it especially susceptible to deforestation and habitat degradation through logging, shifting cultivation and clearance for agriculture. Furthermore, viable populations require vast tracts of forest to survive, exacerbating its susceptibility to habitat fragmentation. These problems are compounded by widespread hunting and trapping for food, and trade in pets and casques. Hunting is the primary threat to the species in Arunachal, India. A report from the Wildlife Extra organisation details poaching incidents with regards to Hornbills.

Wildlife Extra stated:

The unique and intriguing breeding habits that caught Pilai Poonswad attention are central to the birds’ plight. Each hornbill pair seeks out a suitable hollow – 15 to 40 metres above the ground in the trunk or branch of a Neobalanocarpus, Dipterocarpus or Syzygium tree – in which to raise a single chick. When a suitable cavity is found, the female walls herself in, using mud supplied by her mate and regurgitated food, to hatch and rear her chick. The male feeds them for the next three months and, if he fails, both mother and chick may perish. The birds consume up to 80 different kinds of fruit, scattering the seeds over many hectares of forest. With other seed-distributing animals such as monkeys now scarce, the hornbill has become pivotal in maintaining the integrity of the forest. But the birds rarely spread the seeds of the trees in which they nest: if these disappear, the hornbills too will vanish – and the trees and plants they help propagate will soon follow.

Click the link above via the [report] to read more on this very fascinating conservationist.

My name is Dr Jose Carlos Depre, MD, B.Env.Sc, BSBio, D.V.M. I myself have been working within bird, tree kangaroo and pachydermata conservation, rescue and reporting for over fifteen years.

Within these unique, wonderful and exhilarating years I have witnessed one of my favorite species of animals [birds] declining to worrying levels that is now so concerning it has led to sleepless nights for many years. Should we continue to see such catastrophic population decreases of birds we’ll eventually witness alarming declines of plants and trees. The same applies with insects and herbivorous mammals too.

Like insects birds are incredibly important for both human and animal survival. The vast majority of all bird species rely on plants for their staple diet. On consuming fruits, leaves, flowers Etc, the very seeds within the birds diet of life needed to continue seed dispersal will be lost should all bird populations go extinct. Should this occur we selfish humans will then become the Planets seed disperses. Think about that next time you fell a tree or rip a plant up.

Dr Jose. C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Thank you for reading and please share fare and wide to create as much awareness for all Hornbills as possible.

Endangered species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

Endangered Species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

This Fridays endangered species I speak up about the now (not co common Cheetah). Endangered Species Watch Post (ESP) tries to limit the amount of commonly known specie on the platform, however due to recent declines we’ve now included the specie within the (ESP).

Listed on the ‘threatened list’ of (endangered species) as vulnerable, the common Cheetah was formally identified by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (1739 in Weißensee, Thuringia – 1810 in Erlangen), often styled I.C.D. von Schreber, was a German naturalist. (Image Cheetah, photographer unknown).

Identified back in 1775 there remains a total of some five sub-species known that inhabits north, south, west and east Africa. The sub-species A. j. venaticus is known only to inhabit Iran. Some very contradictory reports state there may or may not be populations living within Central India too.

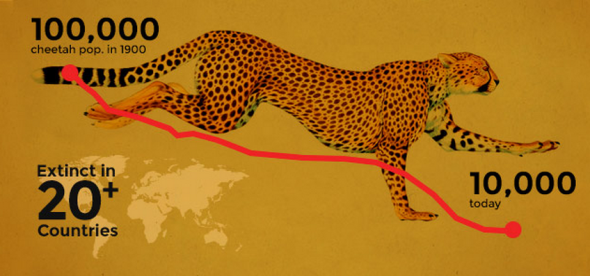

From 1996 to 2002 A. jubatus populations haven’t increased of which this amazing hunting cat commonly known as the Cheetah or (Hunting Leopard) continues to sit at (vulnerable listing). Further population declines will most certainly see the specie qualifying for the category of (endangered). Should this occur the African Cheetah will become the first specie of big cat within the new millennium to hit endangered level.

Cheetahs have disappeared from some seventy six percent of their known historical range which now overtakes that of the Panthera leo (Lion). African populations are considered ‘widely common’ however still known to be sparsely populated. Meanwhile in Asia the Cheetah has practically vanished which is why we must do more to protect the last known remaining Africans populations before further extinctions occur. Cheetahs were known to be quite common throughout Mediterranean and the Arabian peninsula, north to the northern shores of the Caspian and Aral Seas, and west through Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan into central India However this is no longer the case.

One reason for for Asiatic Cheetah population declines was due to live captures of the animal which were trained to hunt other fauna. Unfortunately that was not the main reason why the specie spiralled into near extinction. The primary threat was Cheetah prey decline. This same problem has also been noted as effecting other big cats within Africa and Asia too. Agriculture, over-unregulated-hunting, over-culling, urbanization and habitat destruction via humans, has all played a significant role pushing the species furthermore into the realms of near extinction. Within Iran the sub-species A. j. venaticus is known to be (critically endangered)

In Tunisia Cheetahs were known to roam freely, however there are no known populations remaining within the country. The El-Borma region, near the Algerian boundaries, was probably among the areas where Cheetahs have last been seen in 1974 and documented. Reports compiled back in 1980 now tell us the specie is incredibly rare (if not regionally extinct already). Recently hunters yet again stated that (hunting) has never impacted on the species whatsoever. That’s a complete barefaced lie by members of (PHASA) Professional Hunting Association of South Africa and (DSI) Dallas Safari International.

Cheetahs became extinct from most of the Mediterranean coastal region and easily accessible inland habitats of El-Maghra and Siwa oases one decade after being widely distributed in the northern Egyptian Western Desert until the 1970s. The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands). Please view images lower down the article.

“The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands)”…

Current data on Cheetah population within Eritrea, Sudan and Somali is unknown. Populations within these three countries could very well already be extinct. Reports conducted within most “known Chad Cheetah zones” have sadly concluded the species is no longer present within the of much African country either, 2008 surveys did pick up few roaming species within Southern Chad though. Few populations remain within Central Sahara although to what extent is again unknown.

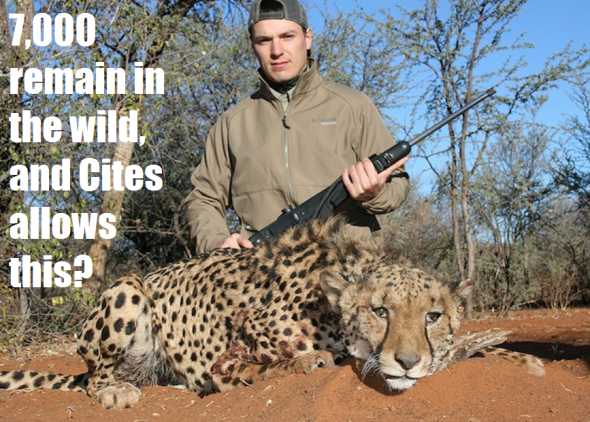

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Within the African countries of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, and Democratic Republic of Congo again population counts are not known. (Its’ quite possible that the species has already gone extinct). Cheetahs are already officially extinct within Burundi and Rwanda. Reports have sadly confirmed the species is also extinct within Nigeria. Poaching and over-hunting have wiped all populations out within the three central African countries. A 1974 study ‘suggested’ that few populations may be occupying both Cameroonian boundaries and Yankari Game Reserve. This report is though mere speculation and not confirmed evidence.

EXTINCTIONS TO DATE

Regional Extinctions

Extinctions have already occurred within; Burundi; Côte d’Ivoire; Eritrea; Gambia; Ghana; Guinea; Guinea-Bissau; India; Iraq; Israel; Jordan; Kazakhstan; Kuwait; Oman; Qatar; Rwanda; Saudi Arabia; Sierra Leone; Syrian Arab Republic; Tajikistan; Tunisia; Turkmenistan; United Arab Emirates; Uzbekistan and Yemen.

Possible Extinctions

Afghanistan; Cameroon; Djibouti; Egypt; Libya; Malawi; Mali; Mauritania; Morocco; Nigeria; Pakistan; Senegal, Uganda and the Western Sahara.

Known Endemic Zones

Algeria; Angola; Benin; Botswana; Burkina Faso; Central African Republic; Chad; Congo; Ethiopia; Iran; Kenya; Mozambique; Namibia; Niger; South Africa; South Sudan; Sudan; Tanzania, United Republic of; Togo; Zambia; Zimbabwe. (Updated 2015)

2015 WILD POPULATION COUNTS

(Please note the following populations below are wild and not captive nor farmed)

Reintroductions of Cheetah populations have taken place within Swaziland however to what extent the populations are within Swaziland is unknown.

What we know to-date is that populations within the “Southern Africa” (not just South Africa) hosts the largest populations at roughly some 5,000+ mature individuals. Botswana and Malawi holds roughly 1,800 mature individuals. Populations are unknown within (Angola) and ‘considered possibly extinct’. Mozambique holds some 50-60 mature individuals, Namibia 2,000. SOUTH AFRICA holds some 550 mature individuals, Zambia some 100 mature individuals, Zimbabwe 400. A large proportion of the estimated population lives outside protected areas, in lands ranched primarily for livestock but also for wild game, and where lions and hyenas have been extirpated. So we do question why trophy hunting and unregulated hunting still persists out of farmed areas.

Ethiopia, southern Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania holds an estimated (2,500 mature individuals) however due to intense hunting pressure, poaching and habitat destruction this number could be much lower. (There is NO evidence that hunting within any of the ‘legal zones’ has increased Cheetah populations whatsoever”. Furthermore I challenge all hunting organisations within the legally allowed hunting areas to prove myself wrong? The largest population (Serengeti/Maro/Tsavo in Kenya and Tanzania) is estimated at 710.

Kenya hosts some 790+ mature wild individuals, Tanzania 560+ to 1,100 individuals. Uganda, Gros and Rejmanek (1999) estimated 40-295 with a wider range in the Karamoja region, whereas now Cheetahs have been extirpated and just 12 are estimated to persist in Kidepo National Park and surroundings. North-West Africa the species stands at no fewer that 250 mature individuals (if that).

Within Iran the ‘sub-species’ of Asiatic Cheetah - A. j. venaticus (if still extanct) stands at some 60-100 mature individuals. We do like the fact the conservation trustee is a known hunter allegedly supporting Cheetah conservation. We’ve yet to see an real improvement of Iranian Cheetahs in the country (more money talk)…

The overall “known Cheetah population” for Asia and Africa is by far more threatened that the Lion. To date there are some 7,000 known mature individuals remaining within the wild but no greater than 10,000. This sadly make the Cheetah by far more threatened than Panthera leo. African Lion populations stand at some 15,000 to 13,000 maximum. As the Cheetah population will not likely exceed 10,000 individuals - the species therefore qualifies for (vulnerable status).

Nowell and Jackson stated that Cheetah populations in the past have undergone some alarming declines, now it would seem that history is re-repeating itself (this time the specie may not survive). The Cheetah exhibits remarkable levels of genetic diversity in comparison and compared to other wild felids, so there could be a high chance the species may make it back from the near brink of extinction within the wild.

Problem is poaching and over-hunting then wasn’t as prolific as it is today. Scientists stated that interbreeding among other individuals had saved the species from bottleneck declines in the past. This history dated back some 10,000 years. Sport hunting then wasn’t an issue as it is today, so in all fairness the species could be hunted into extinction illegally or legally (with much thanks to Cites on the ‘legal part’). So in all honesty we may lose the Cheetah before the Lion.

While the causes of the Cheetah’s low levels of genetic variation are unclear [back then], what is clear is that large populations are necessary to conserve it. Since Cheetahs are a low density species, conservation areas need to be quite large, larger than most protected areas. Major areas of the African continent are being overtaken by humans, agriculture to cope with human expansion and deforestation. No longer is it a case of ‘if’ rather than ‘when’….

MAJOR THREATS

Cheetahs are ‘hunted for sport and trophies’, as well as handicrafts products. Live animals are also traded - the global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining. Pest animals are also removed.

In Eastern Africa, habitat loss and fragmentation was identified as the primary threat during a conservation strategy workshop (2007). Because Cheetahs occur at low densities, conservation of viable populations requires large scale land management planning; most existing protected areas are not large enough to ensure the long term survival of Cheetahs. A depleted wild ungulate prey base is of serious concern in northern Africa. Cheetahs which turn to livestock are killed as pests. Conflict with farmers and depletion of the wild prey base are also considered significant threats in parts of Eastern Africa.

In Iran, the Asiatic Cheetah A. j. venaticus is threatened indirectly by loss of prey base through human hunting activities. In addition, most protected areas are open to seasonal livestock grazing, which potentially places huge pressure on the resident ungulate populations through disturbance and potential competition. Additionally, domestic dogs accompanying the herds present a likely threat to both Cheetahs and their prey. An emerging threat is the possibility of fragmentation into discontinuous subpopulations as a result of increasing developmental pressures (mining, oil, roads, railways); this is particularly the case in Kavir N.P., currently the north-western limit of the Asiatic Cheetah’s range.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Conflict with farmers and ranchers is the major threat to Cheetahs in southern Africa. Cheetah are often killed or persecuted because they are a perceived threat to livestock, despite the fact that they cause relatively little damage. In Namibia, very large numbers of Cheetahs have been live-trapped and removed by ranchers seeking to protect their livestock (from government permit records, Nowell [1996] calculated that over 9,500 cheetahs were removed from 1978-1995). While removal rates have fallen, in part due to intensified conservation and education efforts, many ranchers still view Cheetahs as a problem animal, despite research showing that Cheetahs were only responsible for [3% of livestock losses] to predators. Although Cheetah in Iran have been killed because of predation on livestock, since 2003, there has been no direct evidence of killing Cheetahs, though it is likely most incidents go unreported.

“Cheetahs are also vulnerable to being caught in snares set for other species”.

Another threat to the Cheetah is interspecific competition with other large predators, especially lions. On the open, short-grass plains of the Serengeti, juvenile mortality can be as high as 95%, largely due to predation by Lions. However, mortality rates are lower in more closed habitats.

CITES [allows legal trade in live animals and hunting trophies under an Appendix I] quota system (annual quotas: Namibia - 150; Zimbabwe - 50; Botswana - 5). This was accepted by CITES as a way to enhance the economic value of Cheetahs on private lands and provide an economic incentive for their conservation. The global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining; Cheetahs [breed poorly in captivity] and in 2001 [30% of the captive population] was wild-caught. While analysis of trade records in the CITES database shows that these countries have reported almost no live exports since the late 1990s, Conservation groups are concerned that there is a substantial illegal cross-border trade in live animals.

There is also concern about illegal trade in skins, as well as capture of live cubs for trade to the Middle East. There is an increasing trade in cubs from [north-east Africa into the Middle East], but there is currently little trade in cubs from the Sahel region, where it was previously considered a major problem. Cheetahs are active during the daytime and there is concern that they can be driven off their kills by [tourist cars crowding around, or mothers separated from their cubs]. Burney (1980) conducted a study and concluded that [tourist cars did not seem to harm cheetahs, and in fact sometimes helped, as cheetah chases more often ended in a kill when there were cars around, distracting prey, providing cover from which to stalk, or otherwise waking Cheetahs up to notice prey in the area]. However, [tourist numbers have risen sharply by then, and its potential impact on cheetahs remains a concern].

The Eastern African Cheetah conservation strategy identified four sets of constraints to mitigating these threats across a large spatial scale. Political constraints include lack of land use planning, insecurity and political instability in some ecologically important areas, and lack of political will to foster Cheetah conservation. Economic constraints include lack of financial resources to support conservation, and lack of incentives for local people to conserve wildlife. Social constraints include negative conceptions of Cheetahs, lack of capacity to achieve conservation, lack of environmental awareness, rising human populations, and social changes leading to subdivision of land and subsequent habitat fragmentation. These potentially mutable human constraints contrast with several biological constraints which are characteristic of Cheetahs and cannot be changed, including wide-ranging behaviour, negative interactions with other large carnivores, and potential susceptibility to disease.

Disease is a potential threat to the Cheetah, as its reduced genetic diversity can increase a population’s susceptibility. However, the most serious disease mortality thus far documented in wild Cheetahs was from naturally occurring anthrax in Namibia’s Etosha National Park; Cheetahs, unlike other predators, do not scavenge carcasses of ungulates killed by anthrax, and thus [had no built-up immunity] when they preyed upon springbok sick with the disease. The Cheetah’s low density may offer some measure of protection against infectious disease; for example, Cheetahs were not affected by an outbreak of Canine Distemper Virus in the Serengeti National Park which [killed over 1/3 of the Lion population]. Serological surveys of Cheetahs on Namibian farmland indicate some exposure and survival of the disease.

We are losing the Cheetah faster than the specie of Lion. Although some regulations are in place with the species listed on Appendix I (Cites) its quite likely we’ll lose wild populations should hunting, poaching and unregulated hunting not stop now.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Sources; Cites, Red List, Wiki, Wild Forum, DEA, CCG, DSI, PHASA, Cambridge University, Oxford University.

Endangered Species Monday: Eos histrio

Endangered Species Monday: Eos histrio

This Monday’s endangered species watch post I speak about an all time favorite bird of mine commonly known as the red and blue Lory. Generically identified back in 1776 as the Eos histrio, the species of bird is unfortunately listed as endangered. (Image: Eos histrio)

Identified by Professor Philipp Ludwig Statius Muller (April 25, 1725 – January 5, 1776) Dr P.L.S Muller was a German zoologist. Statius Muller was born in Esens, and was a professor of natural science at Erlangen. Between 1773 and 1776, he published a German translation of Linnaeus’s Natursystem.

The supplement in 1776 contained the first scientific classification for a number of species, including the dugong, guanaco, potto, tricolored heron, umbrella cockatoo, red-vented cockatoo, and the enigmatic hoatzin. He was also an entomologist.

Endemic to Indonesia populations are decreasing like many birds of its kind now within the country. The red and blue Lory was listed as endangered back in 2012 of which population sizes haven’t really increased since this time-frame. Back in 1999 a rather crude evaluation was undertaken by scientists that estimated the population to be standing at roughly 8,500 to 21,400 birds. This evaluation would then place the number of “mature individuals” at a rather depressing 5,400 to 14,000, hence its qualification for the listing of [endangered].

Red and blue Lory can be mostly found on the Talaud Islands (almost exclusively on Karakelang) off northern Sulawesi, Indonesia although, it was previously known to be abundant. Populations have declined fiercely on Karakelang of which its population sizes as explained stand at around 8,500 to 21,400 birds. The nominate subspecies, known from the Sangihe Islands, is probably now “extinct” however, further scientific evaluations around have still to confirm a sub-species extinction.

Diet will normally consist of fruit and insects of which the red and blue Lory will normally collect said foods in dense forest and woodland. Coconut nectar and cultivated fruits from agricultural land have been documented to be part of the red and blue Lory’s diet too.

Image: Suspected extinct sub-species; Extinct subspecies E. h. histrio and E. h. challengeri.

Red and blue Lory’s are recorded at high densities in primary rain-forests rather than low densities. The species will at times tolerate some secondary rain-forest however, it must be noted high density primary rain-forest remains the - birds preferred habitat. E. histrio are not known to commonly build nests like some species of forest dwelling bird do within the family of Psittaculidae. Normally the species can be witnessed nesting within holes in trees which at times is rather comical if you’ve ever seen the species in the wild as I have.

Image: Red and blue Lory - mates forever.

Breeding time is quite typical from May through to June however, some reports have suggested that the species may nest through to June and/or January. Red and blue Lory’s are not known to be a migratory species however will at times locally migrate to local islands out of Indonesia to roost. These movements though must not be considered or documented as migratory.

Listed on appendix I of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species wild flora and fauna (Cites) the species faces many threats highlighted below for your attention;

Threats

Trade represents a significant and on-going threat to the species. It was widely trapped as early as the 19th century. In 1999, research suggested that as many as 1,000-2,000 birds were being taken from Karakelang each year, 80% (illegally) to the Philippines. This is compounded by the extensive loss of forest, perhaps the main factor underlying its disappearance from Sangihe. The reasons behind habitat loss are small-holder agricultural encroachment into primary forest and (illegal) commercial logging. Furthermore, in 2003 there were plans to develop a commercial banana plantation on Karakelang. The use of insecticides and the transmission of disease via escaped cage-birds to wild populations, have been identified as a further potential hazards.

While conservation actions are underway the species continues to decline at astronomical rates. I doubt that the species will still be around by the time I hang up my gloves and retire. Extinction is sadly looming, occurring all over Asia at alarming rates, its highly unlikely the red and blue Lory will pull through.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Endangered Species Monday: Pseudalopex fulvipes.

Endangered Species Monday - Pseudalopex fulvipes

In this Monday’s endangered species article we focus our attention on the species of fox commonly known as the Darwin fox. Identified by Dr William Charles Linnaeus Martin (1798 - 1864). Dr Martin was an English naturalist.William Charles Linnaeus Martin was the son of William Martin who had published early color books on the fossils of Derbyshire, and who named his son Linnaeus in honor of his interest in the classification of living things.

Listed as CRITICALLY ENDANGERED the species was scientifically identified as Pseudalopex fulvipes endemic to Chile, Los Lagos. Charles Darwin collected the very first evidence of this rather stunning species back in 1834 however was not the primary identifier despite the species name. Since 1989 the fox has been re-monitored to determine its current population sizes and future classification. I am somewhat skeptical that this species will survive into the next five years even with more in-depth wild analysis - the species in my own expert opinion is doomed.

One fox was observed and captured back in 1999 for data and breeding with a further two adults captured back in 2002 in Tepuhueico. That same year it was noted a local as killing a mother and her cubs which amassed to some four Darwin foxes witnessed dead and alive within the wild since revaluation of species began from 1989. Some evidence although (little documented) has confirmed “sightings” of Darwin foxes during the year of 2002 however, these are sketchy reports.

On mainland Chile, Jaime Jiménez has observed a small population since 1975 in Nahuelbuta National Park; this population was first reported to science in the early 1990s. It appears that Darwin’s Foxes are restricted to the park and the native forest surrounding the park. This park, only 68.3 km² in size, is a small habitat island of highland forest surrounded by degraded farmlands and plantations of exotic trees. This population is located about 600 km north of the island population and, to date, no other populations have been found in the remaining forest in between.

Darwin’s Fox was reported to be scarce and restricted to the southern end of Chiloé Island. The comparison of such older accounts (reporting the scarcity of Darwin’s fox), with recent repeated observations, conveys the impression that the Darwin’s Fox has increased in abundance, although this might simply be a sampling bias.

As explained even with a very, very small increase in sightings - populations are declining and sadly we may be reporting in the next year or two an (extinction in the wild) occurring if not a complete extinction overall. Should that happen we’ve lost the entire species for good.

Darwin foxes are said and known to be forest dwelling mammals which could be why environmental surveys are proving to be fruitless. Darwin foxes occur only in southern temperate rainforests. Recent research on Chiloé, based on trapping and telemetry data on a disturbance gradient, indicates that, in decreasing order, foxes use old-growth forest followed by secondary forest followed by pastures and openings. Although variable among individuals, about 70% of their home ranges comprised old-growth forest.

Protected under Chilean law since 1929 the Darwin fox are listed on Cites Appendix II (Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species wild flora and fauna). Conservation actions that are under way in the Nahuelbuta National Park are to increase species populations and establish overall protection within this range. Temuco zoo did hold one single species of which was believed to be held for protective captive breeding however the fox has since died back in 2000.

Threats

Although the species is protected in Nahuelbuta National Park, substantial mortality sources exist when foxes move to lower, unprotected private areas in search of milder conditions during the winter. Some foxes even breed in these areas. This is one of the reasons why it is recommended that this park be expanded to secure buffer areas for the foxes that use these unprotected ranges.

The presence of dogs in the park may be the greatest conservation threat in the form of potential vectors of disease or direct attack. There is a common practice to have unleashed dogs both on Chiloé and in Nahuelbuta; these have been caught within foxes’ ranges in the forest. Although dogs are prohibited in the national park, visitors are often allowed in with their dogs that are then let loose in the park.

There has been one documented account of a visitor’s dog attacking a female fox while she was nursing her two pups. In addition, local dogs from the surrounding farms are often brought in by their owners in search of their cattle or while gathering Araucaria seeds in the autumn. Park rangers even maintain dogs within the park, and the park administrator’s dog killed a guiña in the park. Being relatively naive towards people and their dogs is seen as non-adaptive behaviour in this species’ interactions with humans.

The island population appears to be relatively safe by being protected in Chiloé National Park. This 430 km² protected area encompasses most of the still untouched rainforest of the island. Although the park appears to have a sizable fox population, foxes also live in the surrounding areas, where substantial forest cover remains. These latter areas are vulnerable and continuously subjected to logging, forest fragmentation, and poaching by locals. In addition, being naive towards people places the foxes at risk when in contact with humans. If current relaxed attitudes continue in Nahuelbuta National Park, Chiloé National Park may be the only long-term safe area for the Darwin’s Fox.

No commercial use. However, captive animals have been kept illegally as pets on Chiloé Island.

Current estimates place the species population count at a mere 250 left within the wild.

Thank you for reading.

Please share and lets get this fox the protection it requires through education, awareness and funding.

Links for interest:

Adopt a Darwin Fox.

General Information.

Dr Jose C. Depre.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa.

Donate to Say No To Dog Meat today.