Endangered Species Friday: Ailurops ursinus

Endangered Species Friday: Ailurops ursinus

A. ursinis was identified back in 1824 by Dutchman Dr Coenraad Jacob Temminck - (31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist, and museum director. Listed as vulnerable the species is endemic to Indonesia on the island of Sulawesi of which there remains limited data on this rather fine specimen of marsupial that resides in the family phalangeridae. (Image: Young Bear cuscus)

Populations of the (Bear cuscus) as its commonly known continue to steadily decline even though there are limited - conservation measures in place protecting the species (There remains as yet no data on population size). The Bear cuscus has practically gone extinct within the Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve of which a staggering 95% decline has been recorded within the region alone of which the primary threat within the nature reserve is hunting and trade for pets.

North Sulawesi has also seen a staggering decline identical to the population decreases documented within the Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve too. Yet again hunting and the illegal pet trade are very much responsible, and may very well within the next five to ten years lead to a complete extinction occurring.

As much as I myself hate to say it I am pretty certain from viewing statistical data past and present that extinctions are going to occur even sooner than predicted. Should extinctions occur it proves yet again that poaching is having a disastrous effect onto just about every African and Asian species known.

Habitat loss and forest clearance are all playing a pivotal roll at decreasing populations of this beautifully attractive marsupial. As a conservation and botanical scientist sometimes I wonder to oneself why we even bother to help species of animals and flora when some governments show no support, or respect whatsoever in our quest to protect and serve. Then I remember, my children and their children’s heritage is just as important as mine and the teams fight to protect.

Bear cuscus are known as arboreal marsupials meaning, they mostly thrive and spend the majority of their peaceful and playful lives within trees and dense forest. Unfortunately these forests and trees are slowly dwindling in size primarily for land clearance to support local farms and communities and, not forgetting slash and burn activities. I cannot begin to imagine what these creatures think and feel when destructful and greedy humans destroy their homes and pastures. The feeling of not-knowing-when such harm is to be inflicted must be terrorizing for them.

The genus contains the following single species that is known to be related to the Bear cuscus; Ailurops melanotis that inhabits the Salibabu Island listed as (critically endangered) and endemic to Indonesia on the island of Sulawesi. Typically found in undisturbed tropical lowland moist forests, this species does not readily use disturbed habitats, thus it is not usually found in gardens or plantations. It is a largely diurnal and as explained a arboreal species that is often found in pairs. Diet usually consists of a variety of leaves, preferring young leaves, and like many other arboreal folivores it spends much of its day resting in order to digest similar to the Koala bear of Australia.

Image: Bear cuscus relaxing in the canopy of Tangkoko

The only known conservation actions that are taking place are within in few protected areas, that include: Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve, Bogani Nani Wartabone National Park, Lore Lindu National Park, Morowali National Park, and a host of forest reserves. This species is nominally protected by Indonesian law. Unfortunately even though the species is protected the illegal pet trade still continues of which I myself have on many occasions located small pet shops in Indonesia selling Bear cuscus from rusty, cramped cages.

Threats

The species is threatened by habitat loss due to clearance of forest for small-scale agriculture and through large-scale logging. It is also heavily hunted by local people for food, and collected for the pet trade. Cuscus hunting forays are often planned before special occasions (e.g., birthday celebrations) in order to provide future guests with the greatly appreciated meat. (These inferences are based on some six months of residence among Alune villagers in 1993–95, which included participation in forest activities and standard ethnographic data collection.)

Thank you reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Please donate by clicking the link below and help the board of directors establish their Viet Nam pet and wildlife rescue and rehabilitation clinic today. Without your help we cannot take dogs, cats and small bush meat animals of the streets and into safety. No donation is to small and all donations are greatly and kindly appreciated.

Please donate here:

https://www.facebook.com/SayNoToDogMeat/app_117708921611213

Stay up to date with our SNTDM newsletter:

https://www.facebook.com/SayNoToDogMeat/app_100265896690345

Thank you.

Stay up to date with African and international environmental and animal welfare affairs here:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/International-Animal-Rescue-Foundation-World-Action-South-Africa/199685603444685?fref=ts

Endangered Species Friday - Arborophila rufipectus

Endangered Species Friday - Arborophila rufipectus

This Friday’s endangered species I document on yet another species of bird that’s sadly been added to International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Bird Watch Project. Scientifically identified as the Arborophila rufipectus and commonly known as the Sichuan Partridge the species is listed as endangered - nearing extinction. (Image adult Sichuan Partridge). Listed as a nationally-protected species in China. In 1998, it was recorded in Mabian Dafengding Nature Reserve, where there was estimated to be 192 km2 of potentially suitable habitat.

Identified by Dr Boulton in 1932 the species falls into the phasianidae family. A. rufipectus is restricted to its endemic range of China from which its known to inhabit the south-central Sichuan, China with some sketchy reports of the species documented within Yunnan.

Reporting from Singapore where one of five of our Asiatic Bird Watch Projects are situated, environmental teams stipulated from their visits into China within the past fourteen months, no current camera trappings of the species have been recorded within its native range, or ranges where past census’s have been undertaken.

Furthermore the team exhausted all other searches by widening the search covering a total of 2,100 km2. Observations were undertaken in key areas where it was deemed the Sichuan Partridge may be inhabiting taking into consideration food sources, areas of forest that hadn’t been logged while communicating to local hunters, poachers and, locals within the area.

Graduate Lee Won - International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Bird Watch Project CEO stated “We covered an area over the 1,700 km2 setting camera traps within Sichuan and Yannan (2014-2015). The traps were in place for exactly 14 months of which not one single individual or even a pair of Sichuan Partridges were recorded, which brings me and the team to the conclusion that its quite possible extinctions have already occurred, western environmental organisations have as yet to catch up on this data”.

Lee Won and the team that are working within extreme environments stated that vast deforestation is increasing within the birds natural environment of which enforcement and environmental protection remains to be seen. “If Chinese authorities and the Department of Forests and Environment do not protect the Yunnan forests there will be little flora or fauna remaining within this area by 2030” Won stated. The situation is more than dire, its tragic Lee confirmed.

With populations still recorded as “decreasing” the last known census recorded from 1996-1997 recorded an “estimated” total of 806 to 1,772 mature individuals (final count stood at 1,500-3,749). So from Lee Won and his teams evaluations its quite possible that extinction has occurred of which evidence will be submitted in due course to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Dai bo (2007) stated that new sightings of the Sichuan Partridges have been recorded within Laojunshan Nature Reserve numbering around eighty four individuals, these sightings were recorded from 1998-2002. Kim Won’s Bird Watch Project will be making their way to the Laojunshan Nature Reserve in the next few weeks in the hope to locate any evidence of the birds present occupation within the area. Unfortunately we remain skeptical. As explained from 1996/7 population estimate is likely to be too low, hence it is best placed in the band 1,000-2,499 mature individuals. This equates to 1,500-3,749 individuals in total, rounded here to 1,500-4,000 individuals. (Source IUCN).

Males are territorial and monogamous. Males will stay away from the females before mating and during the incubation period. At all other times, males will roost alongside the females. While females are brooding on the ground, the males will sit near the ground for two weeks and then leave to roost elsewhere. The breeding season is late March while the hatching season is mid-May through mid-July. Once paired, males will guard females 24 hours a day.

Image: Sichuan Partridge fledgling.

When it comes to the general breeding and habitat locations for the partridge, it prefers more local areas far from direct disturbances from human contact. Males have three types of one-syllable call, which are a crowing call, courtship call, and preserving territory call. The syllable duration is significantly different between calls, but the difference of main peak frequency was not significantly different. The vocal behaviors will benefit to preserve mates and avoid the predator pressure so the population could last longer.

The Sichuan partridge lives mostly in southern Sichuan Province, in south-west China. It prefers primary and older planted secondary broadleaf forests, rather than one with human activity close by. Prefers a dense canopy and more open understory. The major habitats (in ranking order) are Primary Broadleaf Forest, old replanted Broadleaf Forest, Degraded Forest, and scrub. It prefers thick shrubs for roosting.

Recent work on the species in Laojunshan Nature Reserve found that the species occurred in secondary broadleaf forest but not in settlements, coniferous plantations or farmland [please note there remains no date regarding recent work]. The same study found that birds typically occurred between 1400 and 1800m above sea level in the reserve, and mostly on gently sloping ground close to water sources. [undated with citation required].

Major Threats

Until recently the main threat was habitat destruction through commercial clear-felling of primary forest, as most remaining primary broadleaved forest within its known range was at risk from logging within 20-25 years. In 1998, a government-imposed ban on logging in the upper Yangtze Basin led to a complete halt in deforestation throughout its range.

There is now a major forest plantation scheme in operation aiming to re-forest ridges and steeper slopes. In general though, habitat is still declining. In some areas, forest is still being cleared for agriculture or illegally logged, although this has been “alleged to be on a small scale”. Many people enter the forest to collect bamboo shoots, firewood and medicinal plants in spring and early autumn, which creates substantial disturbance during the breeding season, and additional disturbance is caused by livestock either grazing in, or moving through, the forest.

The species is also illegally hunted. Hydroelectric schemes and the resulting reservoirs in the valleys below its mountain forest habitat cause indirect future threats as the people they displace will be moved to higher locations in close proximity to the remaining forest, putting it under increased pressure.

Further assessments on the species and other endemic species will continue through to next year. I hope to update you on my teams current goals and objectives.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre.

www.speakupforthevoiceless.org

Please support the organisation Say No To Dog Meat this Malbok Festival from July to August 2015.

Endangered Species Monday - Axis calamianensis

Endangered Species Monday - Axis calamianensis

This Mondays endangered species article we take a brief look into the secretive and rather elusive life of the Calamian Hog deer scientifically identified as - Axis calamianensis the species is also commonly known as the Calamanian Deer, Calamian Deer, Calamian Hog Deer or the Philippine Deer.

(Pictured above: Calamian Hog stag)

A. calamianensis was formally identified back in 1888 by Dr Pierre Marie Heude (1836–1902) was a French Jesuit missionary and zoologist. Born at Fougères in the Department of Ille-et-Vilaine, Heude became a Jesuit in 1856 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1867. He went to China in 1868. During the following years, he devoted all his time and energy to the studies of the natural history of Eastern Asia, traveling widely in China and other parts of Eastern Asia.

From 1986 - 1990 A. calamianensis was listed back then as vulnerable however, since this time much has changed regarding the species habitat, and way of living. From 1994 Dr Groombridge identified the need to re-list the species as (endangered) of which a further evaluation after a more in-depth census was concluded (1996) showed the species to be verging near extinction. The last “population census” undertaken in 1996 confirmed the species was still endangered, which led to evasive and aggressive conservation projects to be put into action to preserve the species.

Image: Calamian stag a little uneasy on his feet

Endemic to the Philippines the species is restricted to the Calamian Islands in the Palawan faunal region. The species occurs on three of the four larger islands of Calamians, i.e. Busuanga, Calauit and Culion. Sketchy reports have suggested the species also occurred on at least nine other related islands too however, little evidence backs these claims up.

Reports have confirmed that localized extinctions have occurred in some (78%) of these islands; (Bacbac, Capari, Panlaitan, Galoc, Apo, Alava and Dicabaito), and to survive on only two of these islands, namely Marily and Dimaquiat. A. calamianensis is not known to occur anywhere else from outside of its now fragmented ranges.

Commonly viewed within most of its native range back in the middle 1940’s population sizes have seriously diminished since the late 1990’s. While many drastic declines were seen throughout the 1990’s one area that didn’t see population declines was that of the extreme south of Culion, by the mid-1970s.

By the time the Calauit Island Game Preserve and Wildlife Sanctuary was created, in some way to preserve species populations, conservation actions were already to late of which populations had declined quite rapidly. Reports placed the population size from 1,900 “individuals” which equated to around 250 “mature individuals (if that).

Recent surveys from 2006 showed quite drastic declines of which hunting was yet again the main primary cause for the species nearing extinction (many hunters try to defend and debate this - yet the evidence is there in black and white for them all to view). Despite a negative outlook from the last “official” 2006 census populations were still said to be quite widespread in Calauit, Busuanga and Culion. The 2006 census conducted by environmentalists, Rico and Oliver also confirmed the species populations were quite dense on the islands of Marily and Dimaquiat.

The overall reports into present population sizes though is not good, and its with sad regret to report that populations are continuing to decline at a very rapid rate, despite the species coming under some protective plans there really is no real “protection or even law implemented into action” to protect this species for future generations to come. Listed on the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (Cites) Appendix I localized hunting for food continues to place the entire species in “great danger of nearing extinction” within the next five to seven years. However I must state that “should” extinctions occur in the wild, captive breeding programs are already in place in the hope to later reintroduce the species into a newer, and safer habitat.

Image: Doe and Stag

Current plans to preserve species are that of protective breeding programs for later reintroduction back into the wild. San Diego Zoological Gardens currently hosts some fifty four (54) inhabitants successfully bred within the zoo and managed well.

Threats

Currently research has proven the local people to hunt the species for food and use within dress and musical instrument production. Hunters within the species endemic island ranges are known to hunt the species for its antlers for use within the home as a decorative piece. Antlers are prized among the locals.

The species is threatened due to hunting pressure and human settlement and agricultural expansion over its very limited range, coupled by the evident lack of effective and sustained enforcement of the strong local protective legislation.

Hunting was particularly severe during the mid-1970s, but seemingly declined in most areas during the 1980’ and 1990’s, except on Calauit where hunting pressure increased dramatically following the resettlement of the island by former residents under the auspices of the ‘Balik (Back to) Calauit Movement’. In 1986, 51 out of the 256 families evicted from the island ten years earlier had re-settled on the island, and by 1992 the settlers numbered nearly 500 people.

Much of the hunting of the species is recreational, and also to provide venison to the local markets. On Calauit, introduced African ungulate populations are increasing but are probably not competing with Calamian deer. A presidential proclamation that precluded removal or control of exotic species, and the movement or management of Calamian deer on Calauit Island was recently amended, thereby also potentially enabling the better future control of the exotic ungulate populations, though in fact many of these populations have also been seriously reduced by poaching.

While relatively large parts of Busuanga and Culion Islands are still undeveloped and sparsely inhabited, there are no proper reserves on either.

The following conservation actions are in place or still under amendment:

1. Monitor current status on all the three islands and determine population trends. Evaluate levels of hunting and habitat loss.

2. Strengthen existing protected area system via establishment of new (additional) reserves and development and implementation of properly structured conservation management plan for Calauit that includes improved infrastructure, and measures to combat poaching.

3. Agree and establish a zoning system within Calauit in collaboration with all relevant stakeholders, which enforces strict protection of the core area.

4. Establish protected areas on Culion and Busuanga, based on habitat and deer status surveys.

5. Undertake behavioral and ecological research of Calauit deer to determine management requirements. Conduct

more detailed studies in selected areas.

6. Initiate a conservation education program using Calamian deer as a flagship species to promote a wide variety of related conservation activities, including combating the bush meat trade.

Unfortunately due to the species being so rare there remains very little video data on the animal. Below and included for your information depicts a captive breeding program, and not a public zoological garden. Captive breeding programs in most cases forbid the public from entry. Children can be heard in the background however we must note, protective breeding programs are out of public site. Images above include other species of red and velvet deer too. As explained due to such rarity of this animal obtaining any real positive data of the animal has proved at the best of times difficult. Please contact myself below for further information or questions.

Thank you for reading

Dr Jose C. Depre.

Endangered Species Friday - Bos javanicus

Endangered Species Friday - Bos javanicus

“Thus, the hunting is the proximate cause of decline”

Hunters often demand that we prove to them such a sport or just hunting for food say hasn’t ever pushed a species into nearing extinction or extinction within the wild. The Bos javanicus is under threat from hunters and poachers. (image above - female Banteng)

This Friday’s endangered species article we focus our attention on the Banteng as its commonly known identified back in 1823 by Dr Joseph Wilhelm Eduard d’Alton (August 11, 1772 – May 11, 1840). Mr d’Alton was a German engraver and naturalist who was a native of Aquileia (today part of Italy). He was the father of anatomist Johann Samuel Eduard d’Alton (1803–1854).

He studied in Vienna, and later worked in several locations, including Weimar and Jena. Afterwards he moved to Würzburg, where he worked with embryologist Christian Heinrich Pander (1794–1865). He later taught art history and architectural theory at the University of Bonn, where in 1827 he became a “full professor” of art history. From 1831 to 1840, d’Alton was a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts. One of his famous students in Bonn was Karl Marx. ~Wiki.

The Banteng is listed as (endangered) and is endemic to the countries of Cambodia, Indonesia (Bali, Jawa, Kalimantan), Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia - Regionally Extinct, Sabah), Myanmar, Thailand and lastly Viet Nam.

Unfortunately the species is now known to be “regionally extinct” within the countries of Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam and India. From 1986 to 1994 the species was listed only as (vulnerable) however, due to mass deforestation, poaching, habitat destruction and unregulated hunting not forgetting increasing human population the species has since been listed as (endangered) from 1996 to 2000.

Recent surveys have since established where localized extinctions have occurred (listed above). Furthermore new observations of this rather unique and stunning wild cattle is still considered to be (endangered) despite new evidence of increasing populations emerging in Thailand.

The species historically occurred throughout China in the Yunnan province. Historical data proves the Banteng was present within the Peninsular Malaysia to the islands of Borneo, Java, and probably Bali (please note that in Bali both domestic and wild cattle are known to coexist).

There is no evidence that the species originated from Bali due to there being no fossil evidence being located thus far. Some “populations” on the island are therefore classified as (domestic) rather than all wild. A point of concern has been noted from Dr Watling that quoted “interbreeding with domestic Bali cattle is a problem and the population is unlikely to consist solely of pure-bred animals”. Dr Wind and Dr Amir had earlier raised similar fears too back in 1977.

The species known to inhabit the island of Bali was introduced and did not originate as explained above. Furthermore the “domestic” Banteng have been introduced into Sulawesi, Sumbawa, and Sumba. Feral Banteng occur in Kalimantan. Introduced Banteng (probably feral animals) occurs on the Indonesian islands of Enggano (off Sumatra) and Sangihe (off Sulawesi).

Domestic Banteng has also been introduced to New Guinea and Australia and there are now large feral herds in the Northern Territory. One may have noticed in local Australian hunting magazines, online or within farms in the Northern Territory hunters now paying large sums of money to kill and trophy mount the species within their homes. Despite the “wild” populations suffering and nearing extinction little money from such hunting projects is even provided to conservation organisations and local communities to preserve the species within its native habitat.

Image: Male Banteng Bull (Males are mostly black whereas females are brown)

Wild Banteng are known to live on the island of Bali (please remember not to confuse domestic with wild populations). Furthermore wild Banteng are known to inhabit the island of Java, Kalimantan [Indonesian Borneo], Sabah (although in Sabah extinctions have been noted but not as yet fully confirmed).

A few populations remain in Sarawak however the species is completely extinct within Brunei. Banteng are extinct within Bangladesh and, in India. There are some conflicting reports that the species never even existed within Manipur (northern India - to note).

Extinctions have occurred sadly in Western Malaysia since the 1950’s. southeast Yunnan around Tongbiguan Nature Reserve, along the border with Myanmar; however, the source for this is unclear; and presence in China should be considered tentative at best. Its quite likely the Banteng in China is extinct too however this must not be taken as confirmed. We remain open on this case until further proof is made available of populations being present within the range as explained above.

The species is still wildly inhabiting within Cambodia, Cardamoms Mountain range, with the bulk of the population remaining in the eastern forests, centered on Mondulkiri Province.

The entire “worlds” population is said to be no fewer than 8,000 mature individuals however could be no fewer than 5,000 if that. In Cambodia, Banteng probably declined by 90% . Listed on Cites Appendix II population trends are declining rapidly despite the fact there are some four sub-species and the largest strong hold of sub-populations is on the island of Java.

Threats

The major threats to Banteng are hunting and habitat loss. In Sabah habitat loss to permanent agriculture is a serious threat, although hunting is equally significant and the species has been rapidly exterminated from many areas there. Habitat loss has also been serious in Java since 1998. Elsewhere, hunting is the most widespread and significant threat, and is exacerbated especially in mainland Southeast Asia by human repopulation of lowland forest areas and associated habitat fragmentation, that is, the very areas where most Bantengs occur.

Image: Domestic Banteng are hung to death every year within Baojiang, Rongshui, Guangxi China. The ceremony is yet another listed threat to the species as it also includes wild Banteng that the locals “and foreign tourists” consider non-cruel, a tradition that’s been ongoing for over 500 years. Wild Banteng are considered more important than domestic - of which places a considerable threat to the population despite some conflicting evidence that wild Banteng populations and few and little within China. Nevertheless the species is under immense threat.

Although huge tracts of suitable habitat were lost in the twentieth century, and continue to be converted, this has probably largely occurred after Banteng have been hunted out. Thus, the hunting is the proximate cause of decline, but habitat loss is continually reducing the maximum population possible if hunting issues were to be controlled.

The magnitude of the threat posed to Banteng by international trade in trophy horns is difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, given the small size of the remaining Banteng population and the number of trophies found for sale in Cambodia, the Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam, during what were essentially opportunistic surveys, it is clearly a major threat on the Asian mainland. The threat posed by use of traditional medicinal substances derived from wild oxen is even harder to determine in the case of Banteng and essentially remains unknown, although it is thought to be a source of significant threat to Gaur.

The most important population in Cambodia is scattered through a forest landscape that encompasses four provinces (Mondulkiri, Kratie, Stung Treng and Ratanakiri) and five conservation areas (Lomphat Wildlife Sanctuary, Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary, Siema Biodiversity Conservation Area, Mondulkiri Protection Forest (including the Srepok Wilderness Area) and Phnom Nam Lyr Wildlife Sanctuary).

Hunting is still rife in much of this area, and forest fragmentation is rapidly accelerating with human population in-migration, infrastructural developments (especially roads), commercial agricultural expansion, economic land speculation and mineral extraction. However, although perhaps less than 20% of this area is well protected from the aforementioned threats and protected area management is only close to effective in two areas, the most significant issue concerning the area is the long-term uncertainty of continuation of effective conservation management of the Srepok Wilderness Area and Siema Biodiversity Conservation Area.

Although conservation efforts for Banteng and many other species have been, in both areas, extremely encouraging for the last few years, both areas face an uncertain future with the possibility of de-gazettment of conservation status of parts of them, the possible loss of adequate external funding necessary to maintain high standards of management, the possible loss of political support necessary to uphold high protection standards and the uncertainties of maintaining a motivated and well-trained staff.

On Java some populations are potentially threatened by heavy predation from Dholes Cuon alphinus (a species I spoke about this Monday). All populations are also threatened by poaching and some, perhaps most, are threatened by habitat loss and degradation. During the 1980s–1990s, when poaching and land conversion were relatively well under control in Javan national parks, the chief threat to the large population of Banteng in Baluran National Park was loss of grazing area to invasion by the introduced tree Acacia nilotica (Leguminosae) that converts open grassland to dense thorny scrub-forest.

Image: Introduced into Australia in the last century the species is hunted for sport despite the species being listed as endangered within its native range - very little money is raised for preservation of the species within Australasia. Hunting remains outside of Australia as the major number number one threat pushing the species and sub-species into more decline.

This plant was introduced (without adequate risk assessment) as part of an attempt to create a living fire-break around the park’s grasslands, wild fire then being adjudged the major threat to the park’s monsoon forests. Since that introduction, repeated cutting of the acacia has led to coppicing into very dense thickets that contain little or no grass or other herbs and are difficult for the cattle to penetrate. Thus habitat loss and poaching are now serious limiting factors in Baluran National Park, and habitat loss/degradation remains a severe long-term threat to be addressed. Lantana camara (Verbenaceae) is also a problem in Banteng habitat in Baluran National Park and elsewhere on Java.

Bali cattle have long been interbred with other cattle: Banteng and Bali cattle can interbreed with both common cattle and mithan (Bos frontalis). Hybrids between Banteng and common cattle (Bos Taurus) of the zebu type are fully fertile; in hybrids between Banteng and Bos Taurus of the European type the males are sterile. Domestic and feral livestock are thus a potential threat to the genetic integrity of wild Banteng populations and a number of reports suggest that wild Banteng does interbreed with domestic cattle.

For example, Hoogerwerf (1970) referred to several sources from the 1930s and 1940s which mention that many groups of Banteng in Kalimantan (particularly East Kalimantan) were no longer pure-bred having interbred with stray domestic cattle. Wharton (1957) also found evidence of interbreeding with domestic cattle in Cambodia; and reports from Myanmar mention that Banteng feed alongside village cattle and occasionally interbreed with them.

In addition to the genetic threat, domestic livestock are a potential source of diseases and parasites. This can have very serious consequences for Banteng which appear to be particularly susceptible to a number of cattle diseases; for example, Banteng populations in Myanmar have been very badly affected by diseases from domestic cattle.

Introgression with domestic cattle is not presently an issue in Sabah; there have been imports of Bali cattle mostly by large cattle farms who house animals in feedlots away from wild populations. Ahmad AH is unaware of any instances of deliberate introduction of Bali cattle or other domestic oxen into forest areas, or of any plantation holders that have deliberately introduced their cattle into the range of wild Banteng. Although integration of livestock into oil palm plantation has been discussed for many years, this has not yet been put into practice.

In all due respects its quite likely were going to lose the species due to unregulated hunting, controlled over hunting, poaching, traditional medicine trade, habitat destruction and fragmentation, land conversion and agriculture.

Video: Female Banteng

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

With thanks and much appreciation to the Environmental Team at - International Animal Rescue Foundation Asia.

Endangered Species Friday: Anas bernieri.

Endangered Species Friday - Anas bernieri

This Friday’s endangered species article I focus on my eighteenth “Madagascan” species of wildlife since establishing International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Endangered Species Watch Post one and half years ago. I very much doubt too that this will by mine or the teams last such species of Madagascan native animal to print on nearing extinction, simply because the island is rapidly being overcome by humans, habitat destruction and poaching.

Endemic only to the Africans island of Madagascar the the A. bernieri as the species is scientifically known was primarily identified back in 1860 by Dr Karel Johan Gustav Hartlaub (8 November 1814 – 29 November 1900) was a German physician and ornithologist.

Dr Hartlaub was born in Bremen, and studied at Bonn and Berlin before graduating in medicine at Göttingen. In 1840, he began to study and collect exotic birds, which he donated to the Bremen Natural History Museum. He described some of these species for the first time. Dr Hartlaub has been described by many leading ornithologists as an expert in bird wildlife and conservation and, has been ranked as one of few such experts that has identified over hundreds species of birds globally.

Listed as (endangered) the species is commonly known as the Bernier’s Teal or just Madagascar Teal. The species is uncommonly viewed within western Madagascar of which it can be found along the western coast and, north east. Bernier’s Teal is known to breed at the Menabe and Melaky on the central west coast, and at Ankazomborona on the far north-west coast. Between July and August (1993) the species was observed at Antsalova and Morondava of which a census recorded a total of some 200-300 mature individuals. Back in 1998 a small flock was observed in Tambohorano totaling some 60-70 mature individuals.

Furthermore in 1998 a new a new breeding colony numbering some 200-300 mature individuals was recorded in Ankazomborona. Meanwhile the population noted at Baie de la Mahajamba was estimated to be between some 100-200 mature individuals. (Please note that due to lack of census counts and close monitoring these population numbers above may differ from any future or now census counts) however the Durrel Wildlife Conservation Trust is helping to preserve one of the worlds most incredibly rare birds.

The total mean population count of which could be lower than the last census undertaken back in 2007 stands at a pathetic and measly 1,200 to 1,700 mature individuals today. However due to mass deforestation, pollution, habitat fragmentation and destruction and, poaching, Etc, its quite possible populations of the A. bernieri have plummeted way below the last 2002 and 2007 census count.

The Madagascar Teal is of the Anas genus and is a dabbling duck. Huge areas of wetlands are being drained or altered for human activities such as farmland, rice paddies and prawn ponds. Their wooded habitat is also being destroyed for timber which effects their breeding. Due to the increase of humans in their area, hunting has also increased for so called sport and meat.

Threats

Listed on (Cites) Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species Wild Flora and Fauna the species is listed on Appendix II of which is threatened by a large number of mostly human threats. The species is now extremely threatened throughout its breeding range, by extensive habitat loss and disturbance. The distribution of known sites suggests that the single subpopulation is being fragmented as areas of habitat become unsuitable.

The species has limited dispersal capabilities and isolation may result in the loss of genetic diversity. Furthermore it is threatened by virtue of being highly specific to a series of habitats - which are themselves threatened - throughout its annual cycle. Conversion of shallow, muddy water-bodies to rice cultivation has been so widespread on the west coast that in the non-breeding season the species now appears to be confined to the few suitable wetlands that are too saline for rice-growing, i.e. some inland lakes and coastal areas such as mudflats.

In 2004, during a dry-season survey in Menabe, this species was only found in saline wetlands. Pressures on coastal wetlands are exacerbated by the movement of people from the High Plateau to coastal regions, which is driven by the over-exhaustion of land. Mangroves are under increasing pressure from prawn-pond construction and timber extraction, which also leads to massively increased hunting. Subsistence hunting during the nesting season and the trapping of molting birds are major threats too. It is considered a delicacy by hunters and was found in markets in Sofia in 2011.

See more here on the video above. http://harteman.nl/pages/anasbernieri

In contrast, the breeding site at Ankazomborona is not threatened by aquaculture and there is little pressure from subsistence hunters, though there is some pressure from “sport hunters”. Breeding birds may suffer disturbance from human activity, such as the collection of crabs. The species is potentially in competition for the use of suitable nest-holes with the Comb Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos, parrots Coracopsis species and nocturnal lemurs, Lepilemur species and Cheirogaleus species, though lemurs are absent in mangroves. Breeding is from December to March. Diet consists of mainly insects.

In all its very likely that we will lose the Madagascan Teal within the wild in next to three to five years unless conservation efforts drastically and rapidly improve and, the Madagascar Ministry of Environment and Forests tackles poaching, habitat fragmentation, destruction and human interference sooner rather than later. I personally believe from my last visit to Madagascar back in 2013 its very unlikely the M. Teal or any other species listed as critically endangered will continue to thrive for years to come. Catastrophic habitat destruction on the island is threatening hundreds of over a hundred species of medium and large mammalians.

How can I help? The “Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust” are currently undertaking amazing captive breeding programs of the Madagascan Teal that is known to be one of the worlds most rarest birds. You can help by supporting the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and making a donation to their organisation that will help increase captive breeding colonies for later release back into the wild. Even if the species cannot be released back onto the island of Madagascar (should extinctions occur), reintroduction programs elsewhere will continue to keep this species alive for future generations to come. You never know the species may be coming to a home somewhere near you soon. Please donate and contact the D.W.C.T <here for further information.

Thank you

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa.

For further information or if you’d like to help in upcoming events this year or in the future please contact the Environmental team here today. [email protected]

Con in Conservation?

Contrary to popular belief native Africans were not the first people on the continent to pursue a career or “sport” of trophy hunting. The history of trophy hunting dates as far back to the early 1800’s when southern and central European hunters sought out large or small game. Not much has really changed since the early 1800’s although hunters did out of mutual respect show much veneration to their kill more than today’s modern hunters that flock to the continent of Africa from far and wide in their droves.

Southern and central European hunters were known to keep the trophy head or entire animal as a sign of prowess however did leave much waste of which little of that waste was provided to local villagers and communities struggling financially or in times of famine when free food was much sough after. Today most professional hunters (PH) or outfitters allege that their trophy kill’s are evenly distributed out to the local communities and villagers in dire need of food.

Today in most of Southern Africa we see a mixture of international citizens hunting animals from lion, elephant, zebra, cheetah, impala down to hippopotamus and plains game. The vast majority of hunters visiting the continent range from northern Europe where hunting has long been associated with their history. Back in the 1800’s northern European hunters within their native range would mostly hunt for meat and in Africa evidence has shown that the majority of northern European hunters do indeed demand their kill or any waste is equally handed out to local villagers and communities. After all its their tradition and a tradition in northern Europe that is steeped in history.

Sport hunting has long gotten up Animal Rights Activists noses which today’s hunting generation rarely follow any rule of the land or continue to practice the family tradition as if its a heirloom. Environmental researchers from the Environmental News and Media team have long argued now that western disrespect within today’s hunting generation is now rubbing off onto our own African citizens that have been witnessed killing animals then parading the parts of bodies of animals or jokingly fooling around with the corpse as if it was nothing more than a piece of shit on ones shoe.

One such hunter witnessed back in 2012 that our investigative team noted last year named as Mr Henning Pretorius from Krugersdorp Gauteng, South Africa didn’t just grotesquely slaughter this non-threatened Zebra below - he then set about jumping on the animals dead back jokingly fooling around and acting as if he was on some rodeo. Hardly professional hunting nor conservation. We will though give him his due respects where given of which the animal was slaughtered - however made into a rug for his own home. The meat was distributed among family members and friends which back in the 1880’s was uncommon.

Since Henning pretorius became aware of this image circulating Mr Pretorius not only demanded its removal but, has been given special cyber protection - I.e his profile has been blocked from the United Kingdom. We do find this move by Facebook rather peculiar as 1. we’re not British citizens or even residents and 2. why has he been given this rather suspicious preferential treatment? Did we touch a sore nerve. Mr Henning has also taken the rather unusual step of removing this image or at least concealing it amidst his other nauseating images that Facebook’s administration platform seems to be protecting.

Kalahri’s Historian on hunting and Animal Rights stated:

Trophy hunting is the most controversial aspect of hunting for opponents of hunting, who argue that modern economics or vegetarianism should eliminate the need for most killing of animals, if not animal domestication entirely.

They see such killing as an issue of morality, citing British fox hunting as an especially inhumane “blood sport.”

Hunting in North America in the 1800s was done primarily as a way to supplement food supplies. The safari method of hunting was a development of sport hunting that saw elaborate travel in Africa, India and other places in pursuit of trophies. In modern times, trophy hunting persists, but is frowned upon by some when it involves rare or endangered species of animal. Other people also object to trophy hunting in general because it is seen as a senseless act of killing another living thing for recreation, rather than food.

In all due respects Henning and Kalahari are nothing more than a CON in Conservation.

Africa holds the largest custodian of lions in the world. However their populations are dwindling quite rapidly. To date and based on the most recent up to date International Union for the Conservation of Natures report a population count of some 30,000 lions remain in the wild. Listed as vulnerable and nearing endangered they remain the second species within the big five that’s populations are actually declining. Central African elephant “populations” could be considered within this count too however based on census reports elephant populations within the central African republic are known to be “endangered” as a population not as an entire species.

The African lions main threat is that of habitat destruction and human species conflict with some reports of “unregulated hunting” as being problematic mostly within Tanzania. However while the IUCN lists certain dangers regarding the lion such as habitat destruction, persecution and unregulated hunting they fail to list the dramatic decrease of male African lions that are required within the prides to keep species intact. Continued hunting of males lion or even female lionesses will eventually have an adverse effect onto lion populations thus pushing this species into the realms of endangerment.

Environmental News and Media has duly noted from 2011 to 2014 a stark increase of eastern and southern European hunters visiting Africa to hunt the big five. Increases from Ukraine, Russia, Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Bosnia and Turkey have been noted. More worrying are increasing numbers of trophy hunters such as Jacine Jadreško from Croatia (pictured below).

Croatian, Albanian, Russian, Czech Republic and Polish trophy hunters are second to that of American hunters with British hunters slowly creeping up. While sport hunting is not currently considered a major threat to the species, habitat loss, a lack of prey and increasing conflict with humans are to blame for the decline in the numbers of African lions, whose numbers have dropped by two-thirds since the 1980s, according to 2014 USDA report. There were 76,000 lions in Africa in 1980, but that number has declined to about 30,000 today.

Zambia has since lifted the ban on hunting lions and cheetahs. The ban wasn’t lifted because lion and cheetah species populations began increasing but more for sustainable wildlife projects. In other words while the ban on hunting was in place funding to secure wildlife from poaching just didn’t hit the target - so - therefore Zambia has limited the ban to generate funding to preserve its natural wildlife.

A Con or practical thinking?

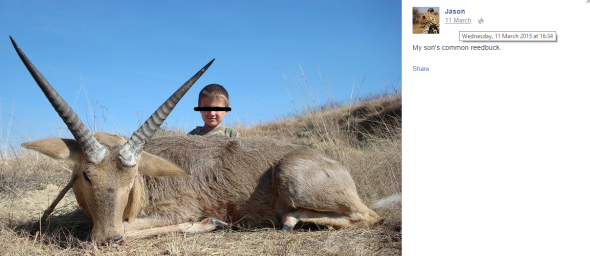

Environmental News and Media’s External Affairs Investigations Dept noted a stark and worrying increase of youth hunters to the continent too. Most African countries hold certain rules in place the forbid a minor under the age of sixteen from carrying or even shooting a loaded rifle. As one can see in the case below this is not so. From Howick, Kwazulu-Natal laws are being flouted daily.

Con or gun conservation?

A further worrying trend were witnessing in South Africa are tiger farms springing up everywhere in the Eastern Cape - for the gun. From 2012 to 2014 Environmental News and Media recorded a total of 63 tiger farms in the Eastern Cape. Since 2012 a further 21 have been established. Tigers are listed as critically endangered - yet are bred and for the gun.

One of the world’s largest and most iconic predators may soon go extinct in the wild - yet in South Africa the species are being bred for for the bloody gun!

Amid all the fuss over global warming and alternative energy, the continued loss of biodiversity is being largely overlooked and forgotten. And the trend may claim its highest profile victim to date in just a couple decades, say conservation groups. For at least a million years tigers have roamed the forests and jungles of Asia, ruling the top of the food chain. But today Tigers are facing a final bow from the world they once ruled as their habitats have been destroyed and their numbers slashed by poaching.

At the start of the twentieth century there were an estimated 100,000 tigers. Over the course of the last century those numbers shrank and several subspecies — the Bali, Javan, and Caspian Tigers — went extinct.

The WWF has released a new report estimating that there are now only 3,200 tigers left in the wild in India, Southeast Asia, Russia, and China. They estimate that within a generation tigers will become extinct in the wild, if drastic action is not taken to conserve them.

Sybille Klenzendorf, director of the WWF-US species conservation program comments, “There is a real threat of losing this magnificent animal forever in our lifetime. This would be like losing the stars in the sky. Three tiger subspecies have gone extinct, and another, the South China tiger, has not been seen in the wild in 25 years.”

World Bank, a multinational financial institution that provides loans to developing countries, is partnering with the WWF in a push to save the beasts.

Keshav S. Varma, program director of the World Bank’s Global Tiger Initiative comments, “Unless we really crack down on illegal trade and poachers, tigers in the wild have very little chance. If the tigers disappear, it is an indication of a comprehensive failure. It’s not just about tigers. If you save the tiger, you are going to save other species. It provides an excellent indicator of commitment to biodiversity. If they survive, it shows we are doing our job right. If they disappear, it shows we are just talking.”

Despite the fact that so few tigers remain, demand for their body parts is at an all time high on the Asian black markets. Crawford Allan, director of TRAFFIC-North America, which monitors the trade in wildlife, comments, “The demand for bones and skin, meat, and even claws and teeth … is driving a major crime campaign to wipe tigers out in the wild.”

Lixin Huang, president of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine has teamed with the WWF to try to fight Chinese natives from using tiger parts in their traditional remedies. States Huang, “Traditional Chinese medicine does not need tiger bones to save lives. What we are dealing with is an old tradition, an old belief that tiger wine can make their bones stronger. That is not medicine, that is from old tradition.”

The WWF’s ambitious goal is to try to get the tiger population doubled to 6,400 tigers in the wild by 2022. To do that, they say they will need $13M USD a year and cooperation from the governments of Bangladesh, China, Europe, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Russia, the United States, Vietnam, and the Greater Mekong region, which stretches across Cambodia, China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

Nearing extinction in the wild - Bred in captivity in South Africa for the gun.

Hardly Conservation is it?

Why are we still hunting Elephants for - Adrenaline Junkies.

As the elephant took a mouthful of food the hunter pulled the trigger exploding a bullet into the back of elephants head leaving this magnificent beast writhing on the ground in a pool of its own blood. What a cowardly bastard.

Why are we still hunting elephants for? This is a question I constantly ask oneself, why? What encourages a hunter to hunt Elephants for? Power, adrenalin, or the fear than an elephant could kill the hunter?.. Much research I undertook about hunters back in the 1990’s revealed that many hunters feel the need to hunt (dangerous game) due to the thrill and rapid adrenalin rush, the cardiac muscle beats faster and harder, surges of hormones are released and the “type” of sexual gratification which has been said to be addictive continues to push hunters to kill more and more.

Back in 1994 I researched a group of American game hunters from Dallas Safari Club. I found in my research that vast surges of adrenalin was mainly responsible for hunters hunting larger and more dangerous game [this of course is not uncommon to most people]. The “adrenalin rush” is in a sense though addictive especially when in the heat of the moment or leading up to a “fight or flight scenario”. In medical terminology we better describe this type of behavior as Impulse Control Disorder (ICD) which is a class of psychiatric disorders characterized by impulsivity – failure to resist a temptation, urge or impulse that may harm oneself, others or in this case the “impulse to kill more dangerous and bigger” game.

These “type” of psychiatric disorders concern oneself more than say those whom have been abused. Furthermore are these type of psychiatric disorders the reason why so many more game hunters are entering Africa to kill. Lastly while the hunter is lavishing within the trills of killing does such killing displayed in videos such as YouTube encourage other people not within the hunting theater to become active in the killing fields? The answer to them two questions is yes, to what extent though I and Professor A. Ball are still investigating in great depth. I’ve included a YouTube video for you to better understand what I am explaining.

As one can clearly see within the video the hunt is very action packed, emotionally charged and driven, one can just feel the edge and thrill. This leads me to my next issue and question which is - why are online video sites such as YouTube allowing such imagery to be broadcast? Research has already proven as of 2010 that large and medium sized game from lions to elephants, antelope and giraffe for instance are not as densely populated within Africa as they were over two decades ago. Hunting activities have been noted to have dropped quite significantly.. Not because activism is stopping hunters or even restrictions but literally because there have been major reductions in wildlife populations over the course of the past twenty years..

Keeping to the main subject many psychiatric disorders feature impulsivity, including substance-related disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, conduct disorder, schizophrenia and mood disorders. Please note that I nor my colleague are labeling any hunter or huntress with any form of mental illness, disorder or disease[s]. We are merely both stating that many hunters we have interviewed such behavioral characteristics have been noted. Hunters are not the only people that can suffer from adrenalin addiction or Impulse Control Disorder, everyone can at some stage in their life suffer from such neurological disturbances, disorders or addictions.

We can all relate to such hormonal and chemical discharges within the brain and body when we were children for example, many youths would feel such rushes of adrenalin within their childhood: Examples of this can be stealing money, their first kiss, sexual activity or as explained participating in an activity that is either immorally wrong or incredibly dangerous.

2004 I researched weather adrenalin was either “psychologically addictive or physically addictive” within youths and weather such addictiveness then spurned youths through their adulthood to then move onto more dangerous activities such as murder, rape, burglaries or in this case large game hunting. Our research thus far has proved such cases of early adrenalin addictiveness and Impulse Control Disorder does in deed in many cases if not monitored or treated later leads to more dangerous activities carried out simply for the sheer “rush or natural high”.

Research carried out by previous consultants and scientists had already proved adrenalin was in a way (psychologically addictive), however never did the research focus on weather such addictiveness spurned individuals in the trophy hunting industry say, to then move onto more dangerous game or even murder. Within this brief article the attention focuses on what drives a trophy hunter to kill more larger and dangerous game, the thrills they obtain and the after-effects of such behavior. The article is not focusing on mass murder, abuse, or anything other than what has been explained.

Myself Dr Jose Depre and Professor Adriana Ball consultant Forensic Psychiatrist have now completed our findings on [What spurs a hunter to kill].. This research document (to be released soon in the Online Scientific Studies of Neurological Disorders in Sweden) 1/6 was aimed at showing other examples as to why trophy hunters hunt. Article [4] details children that were abused that then become the abuser will hopefully be released this June. Please note this is not the title of the 4th article and should one wish to purchase that article in paper back you will need to contact myself nearer the time when I release this book in leading high-street stores..

So is it correct to say that adrenalin is an addictive chemical release that can lead an individual say a trophy hunter, in this case to turn into a dangerous game hunter? Furthermore like opiates or illicit narcotics when one becomes use to the highs of such neurological and/or synthetic pleasures will the individual turn to more dangerous and destructive activities, is adrenalin in its self additive too? Indeed it is of which can be quite difficult for a sufferer to overcome, furthermore failing to treat the sufferer that is clearly on a mission to kill more and more then its quite right to say that adrenalin can lead to more destructive activities being played out. Would this be then the main reason as to why hunters that start of killing small game then go on to killing larger and more dangerous game, in this instance elephants?

The answer to that question is yes. Its quite wrong though to state that “trophy” hunters whom kill animals kill because they were abused as children, or have small penises, lack femininity and masculinity, or need to prove oneself. While there is evidence relating to such human past and present behavior regarding abuse and lack of say (masculinity) there is by far more evidence within the scientific world that indicates and proves hunters can suffer from Impulse Control Disorder or are addicted to adrenaline and noradrenline which are two separate but related hormones and neurotransmitters.

I myself would be more concerned about an “unstable” hunter that is suffering from (ICD) and/or addiction to adrenaline and noradrenline than say, an unstable hunter that needs to prove oneself, or has been abused as a child. Child abuse indeed “may” lead to more sinister and violent activities carried out by the abused however counselling and cognitive therapy can in many cases solve these problems if caught in the early stages before onset of serious mental illness. Proving oneself or weather the individual feels they lack masculinity or femininity is easily treated again with therapy, of which is more a low key behavioral and complex problem treated by a Psychologist rather than a Psychiatrist. Medication is rarely required too.

While the elephant is indeed the prime catch for many experienced hunters and huntresses, the main reasons trophy hunters, say, will hunt is literally for this sheer addictive pleasure of knowing they’re pushing dangerous limits.. In a way one could say that hunting dangerous game is more identical to ones first time stealing from a sweet shop, or being dared by a mate to do something that is either dangerous or very wrong.. Like small game hunting the thrill and adrenalin is there and identical to that of stealing, both hunter and common thief feel the urge after their first mission to push for bigger and better trophies, the need to fulfill ones inner desires is a crave that in itself is very addictive.

Over the past fifteen years I have interviewed many hunters and poachers around the globe of which in my findings I have found that most hunters and illegal poachers that start of with say, small game suffer from as explained Impulse control disorder and adrenaline addictiveness behavioral problems. What I myself did note is that these “obsessive behaviors” seem more related to (trophy hunters) rather than (hunters for food). Trophy hunters are themselves hunting for the sheer thrill while (hunters for food) take only what they require. Furthermore there was quite a lack of “obsessive characteristics” in poachers - which is mainly because they themselves are either being given the order to kill say a Rhino or elephant.

This infant elephant was hunted for what reasons we’ll never fully understand. The elephant posed no threat, it wasn’t a problem animal, in pain nor suffering. There is no real trophy to take home, no tusks, Why?

Elephants are to myself a magnificent gentle giant that has roamed the plains of Africa for hundreds of years. Identified by Dr Blumenbach in 1797 the species listed below killed by Mr Jofie Lamprecht being the African Elephant scientifically identified as Loxodonta africana has been hunted now for hundreds of years. This particular hunter caught my eye, not because of the fact he slaughtered this colossally sized African elephant but more the speech he made after the killing aka [trophy] hunt.. That speech can be read below which is typical and classical behavior of an individual suffering from Impulse Control Disorder and adrenaline addictiveness behavioral problems.

The speech reads:

I honor you my friend. I will follow your round and oval until the end of my time. May your presence in the wilds of Africa continue so that generations from now my prodigy may view your glorious splendor and hunt you like I have had the privilege of doing. Thank you for walking the trails of Africa. Thank you that I can hunt you. Your protein now fills the bellies of many in the surrounding villages. The money you generated will in good faith preserve these wild lands there you walk for your prodigy to be safe and grow old.

Farewell my friend. I will join you when it is my time.

The speech is classical to that of the war with Veii and the Etruscans, under Servius Tullius of which the Rome’s sixth King Servius Tullius went to war with Veii (after the expiry of an earlier truce) and with the Etruscans. King Servius Tullius like many Roman warlords had to prove themselves -fight to the death, after fighting such a glorious and splendid battle did they then lay down their arms and celebrate with a triumph speech. Mr Jofie Lamprecht is in reality no different to King Servius Tullius - however King Servius Tullius was more gentleman like.

Many people have problems that occur repetitively, disrupt their lives and seem completely out of control. Sometimes we’re asked if these problems are examples of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). And indeed, there are some similarities to OCD. Nevertheless, these problems are not considered to be in the same category. So what are we talking about here? Specifically, we’re referring to the category of emotional disorders known as Impulse Control Disorders. The similarity to OCD is seen in the fact that impulse control disorders, like OCD, are repetitive and very difficult for the person to bring under control. Furthermore, like OCD, they greatly disrupt and impair the sufferers’ lives. However, Impulse Control Disorders also differ from OCD in important ways. Impulse Control Disorders, unlike OCD, often do not cause a great deal of distress to the person who has them—that is, unless or until legal authorities are called in. Furthermore, distress, anxiety and upset do not play a very large role in most Impulse Control Disorders. In fact, many of those with Impulse Control Disorders actually report feeling pleasure from their behaviors even though their lives are impaired by them.

When I myself and Professor Ball interviewed all hunters not one hunter showed any signs of distress, anxiety and upset, the last of the hunters whom we interviewed this past month hadn’t hunted elephants or dangerous game such as elephants or lions, rhinos or wildebeest.

No empathy or guilt was shown when they were shown images and videos of other hunters killing. However what was shown on the sudorometer and electrocardiograph was increased heart rate and perspiration which indicated to ourselves that the interviewees were feeling excited. When shown video imagery from YouTube levels of sweat and heart rate increased by 2.5% When asked if “If you had the chance to hunt an elephant now would you do it?” 19/27 hunters said yes. So in reality when we question ourselves why are we still killing elephants, or any dangerous game its quite right to say programs on television and YouTube really are not doing our wildlife any form of good. For example if your shown a video of a chocolate bar advertisement from which you’ve never indulged in that sweet the chances are “that advertisement” will encourage you to purchase that sweet.

The full results of the above examination and all test experiments will be released later this year.

Looking at our past we can also see that elephants were not just hunted for the sheer fun of it..The main reason that elephants were hunted was for their ivory. This is worth a ton of money and so huge numbers of elephants were slaughtered in order to be able to cash in on such a business. With each tusk weighing up to 200 pounds, this was amazing. Early attempts to remove the ivory tusks and to leave the elephants alive didn’t work. The elephants were simply too aggressive for this type of process and it was too dangerous for humans to take part in.

Elephants are taking quite a hit all over Africa and its quite evident from past research and present researching “why” elephants were and still are legally hunted. One cannot just point the blame at natural neurological issues though as I myself have explained, above I’ve clearly detailed why [we still are hunting] from past to present but more from a different perspective of things.

Moving back to just how big a problem adrenalin addictiveness and Impulse Control Disorder’s can be - curing such disorders that are quite natural is more easier said than done. At the end of the day its down the individual hunter and huntresses to come forward should they feel they have an “obsession” or (ICD). One cannot force a hunter to visit a therapist however what we can do is make aware the problems that some hunters if not all believe is quite actually typically normal behavior. One very good article that I do suggest people read is that of Serial Offenders which details much of the above in this book, however its very broken down. Read more here.

Excessive adrenaline build up changes a trophy hunters physiology. The trophy hunter becomes sensitized to the epinephrine and used to what it does to them. Initially it may be difficult to cope with, but after awhile, the individual becomes so accustomed to it that you can function. This is not always the case though as it has been noted adrenaline junkies feed of such fear which in turn provides a type of sexual gratification afterwards and relaxation. Adrenaline sends your brain into full throttle and your wit becomes majorly amplified. This is because your slower brainwaves in the alpha and theta ranges become severely diminished. Alpha rhythms are drowned out by high amounts of mid and high-range beta brainwaves. This leads to further production of dopamine, epinephrine, and cortisol. Trophy hunters have long stated that the majority of the time they hunt is not for the actual trophy but more the “adrenaline hit”.

Author Louis Schlesinger quoted as Professor Ball did “emotional, impulsive murderers are less able to regulate and control aggressive impulses”. If you’ve being paying attention and scroll back up to the very top of the article one will read very identical characteristics relating to narcissistic psychopathic murderers to that of those whom kill large game, dangerous game and small game…

Treatment of Impulse Control Disorders has lagged behind the treatment of many other emotional disorders such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorder. There are some indications that treatments such as Habit Reversal Training may have value for Trichotillomania. However, most of the Impulse Control Disorders beg for more research on potential treatments. Of course, even if we had a plethora of effective treatments, there’s still the problem that most of those with Impulse Control Disorders aren’t all that interested in getting help. Sigh.

Why are we hunting Elephants again?

Thank you for reading - Stay tuned for my book on Impulse Control Disorders and Trophy Hunting.

Dr Jose C. Depre Md, VetMed, EnvStu, Phd