ENDANGERED SPECIES MONDAY | PHOCARCTOS HOOKERI EXTINCTION LOOMING - NATIONAL EMERGENCY.

ENDANGERED SPECIES MONDAY | PHOCARCTOS HOOKERI

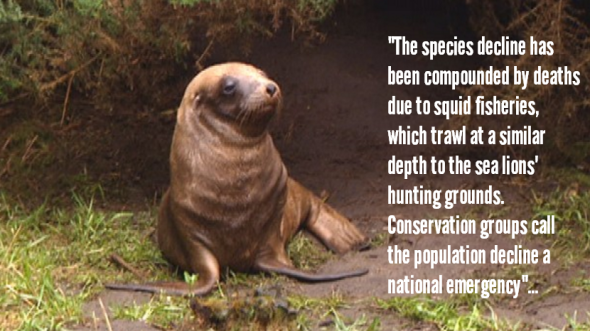

This Monday’s endangered species (E.S.P.) article I’ve chosen to document on the New Zealand sea lion. Image: New Zealand Sea Lion. Credits: Tui De Roy.

Listed as (endangered) the species was identified by Dr Gray back in 1866. Dr Gray John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist Dr George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Dr Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828).

Dr Gray was Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum in London from 1840 until Christmas 1874, before the Natural History holdings were split off to the Natural History Museum published several catalogues of the museum collections that included comprehensive discussions of animal groups as well as descriptions of new species. He improved the zoological collections to make them amongst the best in the world.

Scientifically identified as the Phocarctos hookeri the species was listed as vulnerable from 1994-2008. Unfortunately due to continued population declines the New Zealand seal is now bordering complete extinction within the wild (and things really aren’t looking good neither) Endemic to Australia (Macquarie Is.); and New Zealand (South Is.), the species is also native to the Pacific North West.

To date there is estimated to be no fewer than 3,031 mature individuals remaining within the wild. New Zealand sea lions are one of the largest New Zealand animals. Like all otariids, they have marked sexual dimorphism; adult males are 240–350 cm long and weigh 320–450 kg and adult females are 180–200 cm long aMnd weigh 90–165 kg. At birth, pups are 70–100 cm long and weigh 7–8 kg; the natal pelage is a thick coat of dark brown hair that becomes dark gray with cream markings on the top of the head, nose, tail and at the base of the flippers.

Adult females’ coats vary from buff to creamy grey with darker pigmentation around the muzzle and the flippers. Adult males are blackish-brown with a well-developed black mane of coarse hair reaching the shoulders. New Zealand sea lions are strongly philopatric.

Image: New Zealand Sea Lion Pup. Credits: NZ Fur Seals.

Back in 2012 populations of New Zealand sea lions “were estimated to be standing at a population count of 12,000 mature individuals”. However since that count took place, from (2014) populations have ‘allegedly plummeted’ to all new levels although there doesn’t appear to be any evidence as to why the species suddenly declined - fish trawling and disease have been noted though!.

Like the Maui’s dolphin, the sea lion has come under intense scrutiny this year after research showed its numbers had halved since 1998. It has been classed as nationally critical and if its decline is not stemmed will be extinct within 23 years. A bacterial infection severely reduced breeding in 1997-98, and the species has failed to recover.

Its decline has been compounded by deaths due to squid fisheries, which trawl at a similar depth to the sea lions’ hunting grounds. Conservation groups call the population decline “a national emergency and are calling on stricter by-catch limits and a change in fishing methods”.

BACK IN 2012 THE NEW ZEALAND HERALD REPORTED THE FOLLOWING

In a country with 2800 threatened species, conservation in New Zealand is often about picking winners. The Department of Conservation’s budget and energy can extend only to active interventions for 200 of these endangered species.

Whether a species is protected depends on funding, community input, national identity and research. DoC spokesman Rory Newsam says interventions are often made because the department believes it can “get the most bang for its buck”. But animals and plants are not always invested in because they have a greater chance of survival.

The kakapo receives a relatively large chunk of funding despite being functionally extinct on the mainland. Some ecologists argue too much is spent rescuing the rare parrot, while more crucial parts of our ecosystem are left behind. But the kakapo is protected because it is a charismatic species and the public considers it integral to New Zealand’s ecological identity.

Conservationists say kakapo are a window to New Zealand’s history. They are believed to have inhabited the Earth for millions of years. To kill them off in a fraction of that time is an indictment on the way we live.

Image: New Zealand Sea Lion. Image Credits One Newz.

New Zealand sea lions are known to predate on a wide range of prey species including fish (e.g. hoki and red cod), cephalopods (e.g. New Zealand arrow squid and yellow octopus), crustaceans, seabirds and other marine mammals. Studies indicate a strong location effect on diet, with almost no overlap in prey species comparing sea lions at Otago Peninsula and Campbell Island, at the north and south extents of the species’ breeding range. New Zealand sea lions are in turn predated on by great white sharks, with 27% showing evidence of scarring from near-miss shark attacks in an opportunistic study of adult NZ sea lions at Sandy Bay, Enderby Island.

Image: Dead New Zealand Sea Lion in Fishing Net.

Since 2012 New Zealand conservationists, and the public community have been calling on the New Zealand government to do everything they possibly can to preserve this species. Unfortunately as you can see above fishermen are still accidentally killing the species off. As the species is protected under law and listed as endangered, the New Zealand government must take action against these perpetrators, otherwise extinction will most certainly occur.

The Maori people of New Zealand have traditionally hunted Sea Lions, presumably since first contact, as did Europeans upon their arrival much later. Commercial sealing in the early 19th century decimated the population in the Auckland Islands, but despite the depletion sealing continued until the mid-20th century when it was halted.

Commercial sealing in the early 19th century decimated the New Zealand Sea Lion population in the Auckland Islands, but despite the depletion sealing continued until the mid-20th century. The population has yet to fully recover from the period of over exploitation. At the present time, New Zealand Sea Lions have a highly restricted distribution, a small population, and nearly all of the breeding activity is concentrated in two subantarctic island groups. This restricted and small breeding population in combination makes them vulnerable to disease outbreaks, environmental change, and human activities.

The commercial Arrow Squid trawl fishery near the Auckland Islands reported their first New Zealand Sea Lion bycatch mortalities in 1978. Reported or estimated mortality between 1995 and 2007 averaged 92 animals annually (range 17-143) which was 3.7% of the estimated number of mature individuals in the Auckland Island area. Of particular concern is that most bycatch animals are females (up to 91%). New Zealand Sea Lions are also incidentally caught in other trawl fisheries around the Auckland and Campbell Islands.

Apart from direct mortality, competition and habitat modification caused by fishing activity may also be impacting New Zealand Sea Lion foraging areas. Epizootic outbreaks at the Auckland Islands in 1998, 2002, and 2003 led to more than 50%, 33%, and 21% early pup mortality respectively, and were also responsible for the deaths of some animals from other age classes during 1998.

The source of the suspected bacterial agent and cause of the outbreak and subsequent mortality for the 1998 outbreak are unknown, however the 2002 and 2003 outbreaks have been identified as being caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The future of the New Zealand sea lion doesn’t look good at all. I highly suspect that we’re going to lose the species within 10-20 years (if that). More needs to be done to preserve the species habitat and its current fishing grounds as well as protecting from bacterial outbreaks. Failing this the species will be extinct within 10-20 years max. I am highly doubtful here, which is very rare for me to speak about.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre. PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical & Human Scientist.

ENDANGERED SPECIES FRIDAY | EQUUS FERUS CABALLUS | WILD HORSES OF NAMIBIA.

ENDANGERED SPECIES FRIDAY | EQUUS FERUS CABALLUS

This Fridays Endangered Species Post focuses on a sub species of the E. ferus that inhabits the plains of Namibia, Africa. Image: Klein-Aus Vista - E. F. Caballus.

The species (E. ferus) I believe was identified by Professor Carl Von Linnaeus back in 1758 of which identified quite a large number of horses to be precise, however the E. F. Caballus originates from around 1915. Carl Linnaeus born (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement as Carl von Linné was a Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, who formalised the modern system of naming organisms called binomial nomenclature. He is known by the epithet “father of modern taxonomy”. Many of his writings were in Latin, and his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus (after 1761 Carolus a Linné).

E. F. Caballus isn’t listed on the IUCN Red List that I myself can locate (although is endangered). From 1965 the species was listed as (incredibly rare). Then ‘sketchy reports’ state from 1986 to 1996 the species went completely extinct within the wild, there is no evidence to back this claim up though.

From 2008 the species was ‘allegedly’ re-discovered and listed as critically endangered (although as explained there is no criteria on the IUCN Red List relating to this sub-species). Come 2011 populations had somewhat increased slightly placing the species in the band of endangered?. The criteria relating to extinction I am currently looking into as I believe this report ‘could be incorrect’. There is certainly some image evidence (although not proven) that shows a species ‘identical to the Namibian horse’ during the so called extinction period from 1986-1996. However the sub-species has been reported on since the 1940’s.

From what I know the species is a rare feral desert horse of which populations are believed to be near extinction level. Populations are estimated to be between 90-160 mature individuals. Namibia wild horses generally lead healthy life’s although during times of extreme drought (during the summer months) is when the species is normally reported to be struggling, with a number of deaths reported annually.

The origin of the Namib desert horse is unclear, though several theories have been put forward. Genetic tests have been performed, although none to date have completely verified their origin. The most likely ancestors of the horses are a mix of riding horses and cavalry horses, many from German breeding programs, released from various farms and camps in the early 20th century, especially during World War I. Whatever their origin, the horses eventually congregated in the Garub Plains, near Aus, Namibia, the location of a man-made water source.

During the 1980’s the species was virtually eradicated because locals disliked the horses trampling and eating their crops. Fortunately up until the 1980′ the species has lived a virtually hassle free life. Humans rarely if at all bother them, and there is no evidence to prove the species is under threat from hunters, or the African medicine/animal parts trade. Furthermore there doesn’t appear to be any evidence of poaching neither which is good.

Image: Namibia desert horse and foal.

Namibian wild horses host a number of ‘wild predator threats’ though such as hyenas, blacked backed jackals, and leopards too. Young horses (foals) are normally taken by predators, however adults rarely aren’t.

The harsh environmental conditions in which they live are the main driver of mortality among the Namib desert horse, as they cause dehydration, malnutrition, exhaustion and lameness. Other large plains animals, including the mountain zebra, may have once sporadically utilized the area for grazing during periods of excess rainfall, but human interference (including fencing off portions of land and hunting) have eliminated or significantly reduced the movement of these animals in the area.

The endangered Hartmann’s mountain zebra does exist in the Naukluft Mountain Zebra Park portion of the Namib-Naukluft Park, but their range does not intersect with that of the Namib Desert Horse.

SOURCE: HORSE JUNCTION.

From what I know there is no evidence of wild horses inhabiting anywhere within ‘Southern Africa’, so the theory is these horses may have been imported by the Germans during the last World War, of which after the war the horses were eventually set free to do as they please. While there are numerous speculations and stories - we’ll never truly know where these horses have originated from. Furthermore due to interbreeding genetic testing has proven to be somewhat of a failure too in establishing the true origins of these magnificent beasts.

SOURCE HORSES AND GHOST TOWN CNN.

A further theory although not proven touches on a large vessel carrying thoroughbreds to Australia that unfortunately wreaked near the Orange River. On breaking up the strongest horses are ‘believed’ to have swam ashore to the Garub Plains, the home of the Namib Desert Horse, near Aus, Namibia. As explained though to date there is still no evidence to prove where these horses originated from, moreover all theories haven’t a single scrap of evidence to back such claims up.

Image: Namibia wild horses drinking at water hole.

One of the biggest threats that could today threaten the wild horses of Namibia is that of water shortages. For now we know the horses normally occupy areas where there is sufficient water holes, large man-made or natural lakes. With drought and climate change becoming more problematic within many Southern African countries its likely we ‘could see species extinction occur in as little as five to ten years’.

All the wild horses in the world, with the exception of a single population, originate from domestic stock. Horses were domesticated on the Eurasian steppes 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, and have been in service to humankind ever since. It was on the horse’s back that civilization advanced. Countries were explored, wars were fought, agriculture and industry progressed at the expense of the horse’s freedom.

The only horse population that was never domesticated, and still exists in its true genetic form, is Przewalski’s Horse or the Mongolian Wild Horse. So extinction could occur very soon simply because the Namibia wild horse’s natural born living instincts haven’t really adapted to the extreme wilds of Africa hence why they are commonly located around man-made or natural water sources, and human settlements?

It was reported this year back in April that drought has been responsible for many species of animals dying due to lack of water and available fresh food sources which has prompted the Namibia Wild Horses Foundation (NWHF) to appeal for funds or good quality grass during this more severe period to see the horses through the winter. NWHF was established in 2012 to monitor the well−being of the horses and to marshal funds for buying feed when the need arises during the drier cycles.

Back in April (2016) the (NWHF) stated there is little grass in the horses’ range as the drought has severely affected the central and southern parts of the country. “The foundation fears that without rain there will be virtually no grass left by the onset of winter and as the horses’ condition further deteriorates, numbers will begin to drop dramatically,” the statement reads. Spring is also now approaching Africa of which we may see further prolonged droughts, and even more deaths.

The foundation also expressed gratitude for all generous contributions for the horses during the past six months. This, it said, has provided supplementary feed – a quarter to a third of the horses’ nutritional requirements — in the form of grass and lucern and protein licks, and will sustain the herd until the beginning of June when the next phase will need to be implemented to ensure their survival; (this period is now over and donations are greatly needed to keep these horses alive). If you’d like to donate to the (NWFH) please click the donate button here: DONATE.

Concerning: The April report also highlighted that some 100 ‘old horses and some fouls’ had sadly perished since the beginning of the drought, which to date leaves exactly 160 mature individuals remaining within the desert of Namibia.

Donations to buy grass or lucern for the horses can be made to Namibia Wild Horses Foundation, First National Bank, current account 62246659489 Klein Windhoek branch ( code 281479) and swift FIRNNANX.

The future is uncertain for the species, in my humble opinion I doubt these horses are going to be inhabiting the desert much longer due to the harsh impacts of climate change increasing every year on the African continent. Furthermore due to the species not really having any ‘natural wild instincts from their ancestors’ they’ll continue to rely on humans just to stay alive. If you’d like to help the species please do so via contacting the Namibian Non-Governmental-Organisation above and donate what you can. Alternatively you can I believe volunteer to help preserve Africa’s only wild horse populations known.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Master of Environmental, Botanical & Human Science.

Endangered Species Monday | Tasmanian Devil | Sarcophilus harrisii.

ENDANGERED SPECIES MONDAY | TASMANIAN DEVIL

This Mondays endangered species watch post (ESP) is dedicated to the Tasmanian devil, an endangered carnivorous marsupial that’s roughly the same size as a small domesticated canine. (Image credits: Bicheno Tasmania tourism)

The Tasmanian devil was formally identified back in 1841 by ‘French’ Dr Pierre Boitard (27 April 1787 Mâcon, Saône-et-Loire – 1859) whom was a French botanist and geologist. As well as describing and classifying the Tasmanian devil, he is notable for his fictional natural history Paris avant les hommes (Paris Before Man), published posthumously in 1861, which described a prehistoric ape-like human ancestor living in the region of Paris. He also wrote Curiosités d’histoire naturelle et astronomie amusante, Réalités fantastiques, Voyages dans les planètes, Manuel du naturaliste préparateur ou l’art d’empailler les animaux et de conserver les végétaux et les minéraux, and Manuel d’entomologie etc.

Listed as (endangered), and scientifically identified as Sarcophilus harrisii. Back in 1996 conservation scientists undertook further research on the species thus concluding the species was of ‘lower risk’. Unfortunately since 1996 - things have changed dramatically on the Australian continent. From the middle 1990’s conservationists estimated the mean mature individual total as being - 130,00-150,000 mature individuals.

Spotlighting sightings of Tasmanian devils across the state have declined significantly since the emergence of Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) in the mid-1990s: by 27% by early 2004, by 41% by early 2006, by 53% by early 2007, and by 64% by early 2008. The decline was significantly sharper in regions where DFTD had been reported earliest, such that in north-east Tasmania, mean sightings have declined by 95% from 1992-1995 to 2005-2007, with no indication of recovery or plateau in decline.

Comparison of mark-recapture results in the same area from the mid-1980s and 2007 supports this finding. At the Freycinet peninsula, on the east coast of Tasmania, where the population has been monitored through trapping from 1999 to the present, the population has declined by at least 60% since the disease was first detected in 2001 and the adult population still appears to be halving annually. Other indicators of devil abundance, such as road kills, predation on stock, and carrion removal, also support this conclusion of a substantial decline.

Surveys conducted back in 2007 ‘estimate the (mature) Tasmanian devil populations to be standing 25,000 being the highest estimate’; this equates to around 50,000 individuals. However back in 2004 conservationists stated the (mature populations) could be as low as 21,000 mature individuals. Conservationists have confirmed that due to the rapid spread of Devil Facial Tumor Disease, and other threats such as road accidents and predator kills - acknowledging these provisos, the best estimate of total population size based on current evidence thus lies within the range of 10,000-25,000 mature individuals. Based on threats, gestation, life span this therefore qualifies the species to be entered into [endangered category].

13 Feb 2011, Cradle Mountain-Lake St. Clair National Park, Tasmania, Australia — Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) being treated by scientist for DFTD, Devil Facial Tumor Disease. This is a cancer that is spread by biting or physical contact from one animal to another, Cradle Mountain, Tasmania, Australia. — Image by © Dave Wattsl/Visuals Unlimited/Corbis.

In North-Western Australia Tasmanian devil populations are estimated to be standing at between (3,000-12,500 individuals). Meanwhile - in Eastern South Western Australia populations are said to be standing at 7,000 12,500 individuals.

Other trapping work by the Department of Primary Industry and Water (DPIW) Save the Tasmanian Devil Program broadly support these predictions for DFTD-free regions. However, in central and eastern regions, marked population declines have been detected, in association with the earlier reports of Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD), subsequent to the time of the Jones and Rose survey. The north-west region is thus now thought to support the highest population densities.

The species is not known to be seriously or severely fragmented, however populations on the decline and fast, primarily due to Devil Facial Tumor Disease.

THREATS

Current evidence suggests that DFTD is an infectious, widespread disease, so that any attempt to delineate boundaries between affected and unaffected locations is likely to be outdated swiftly. DFTD has been associated with local population declines of up to 89% since first reported (Hawkins et al. 2006, McCallum et al. 2007), indicated by long-term spotlighting data, widespread trapping and laboratory results. The declines, and the prevalence of the disease, have not eased off in any monitoring sites, and DFTD is present even in very low density areas.

It is estimated that the adult population is approximately halving annually on the Freycinet peninsula with extinction predicted at this site 10-15 years after disease arrival. Declines were most marked in areas where the disease had been reported earliest, in north-eastern and central eastern Tasmania.

Mean spotlighting sightings of Tasmanian devils per 10 km route, obtained from across the core Tasmanian devil range (eastern and north-western Tasmania), have declined by 53% since the first report of DFTD-like symptoms in 1996. The most immediately threatened location is thought to be the region where DFTD was reported prior to 2003: across 15,000 km² of eastern Tasmania.

By 2005, the Devil Disease Project Team had confirmed DFTD in individuals found across 36,000 km² of eastern and central Tasmania. DFTD is now confirmed across more than 60% of the devil’s overall distribution, and there is evidence for continued geographical spread of the disease, so that Tasmanian devils across between 51% and 100% of Tasmania may be, or have already been, subject to >90% declines in a ten-year period. The currently affected region covers the majority of the formerly high-density eastern management unit, involving what was perhaps around 80% of the total population.

Image: Tasmanian devil killed by car/with suspected DFTD.

DTFD has resulted in the progressive loss of first the older adults from the population and then the younger adults so that populations are comprised of one and two year old’s. As female devils usually breed for the first time at age two, they may not successfully raise a litter before they die of DFTD. An increase in precocial breeding indicates some compensatory response, but as yet this appears to have been insufficient to counter mortality.

DFTD behaves like a frequency-dependent disease, probably because the majority of the injurious biting, which is the type of contact most likely to lead to disease transmission, occurs between adults during the mating season. Frequency-dependent diseases, which are typically sexually transmitted, can lead to extinction. Because transmission occurs between the sexes at mating irrespective of population density, these types of diseases lack a threshold density below which they become extinct.

Cannibalism is considered fairly common in Tasmanian devils and renders the species particularly vulnerable to disease transmission. However, modes of transmission of DFTD are not as yet known.

ROAD KILLS:

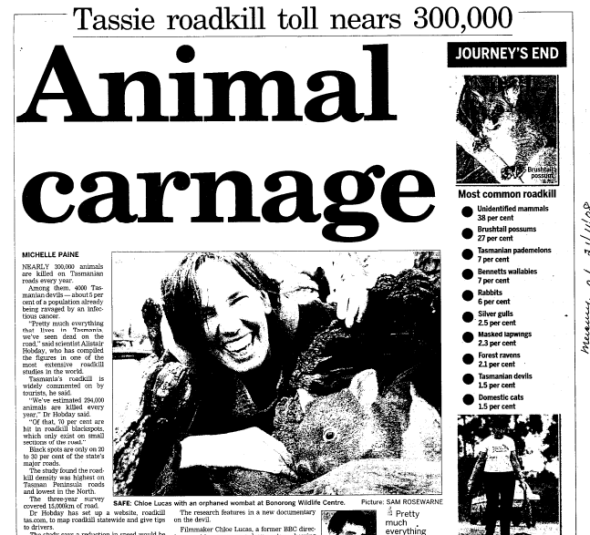

A recent three-year study of roadkill frequency on the main roads of Tasmania estimated 2,205 Tasmanian devils are killed on roads annually. This suggests that 2-3.% of the total Tasmanian devil population are killed on roads (based on an estimated population of 60,000–90,000 individuals at the time of the survey). The roaded parts of Tasmania closely match the core distribution area for Tasmanian devils.

Roadkill was attributed as the cause of up to 50% and 20% of Tasmanian devil death during a recording period of 17 months at Cradle Mountain and 12 months at Freycinet National Parks, respectively. Local extinction and a similar rate of population decline at Cradle Mountain indicates that roadkill can cause local extinction, in which the road becomes a local sink. Future impact is likely to remain at the same level.

Image: Paper cutting relating to 3 year study of fauna road kill.

DOG KILLS:

Reports of about 50 devils killed per year by poorly controlled dogs are served from about 20 dog owners. There is no obligation or incentive for such reports, and generally some hesitance even among those providing them, so the real figures are more likely of the order of several hundred devils killed by dogs each year.

FOXES:

There have been spasmodic, small-scale introductions of the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) into Tasmania since early European colonisation. Early incursions were sometimes efforts at acclimatisation and others for short-term hunting. More recently, there has been at least one accidental incursion (from a container ship in 1998) and credible reports of a concerted, malicious campaign of introduction.

Hard evidence (confirmed scats, carcasses) of foxes has been found in the north-west and northern and southern midlands. Credible sighting reports have come from most of the eastern half of the State including the central highlands and the far north-west, mostly areas where Tasmanian devil populations are suppressed by DFTD.

A commonly held view has been that the abundance of Tasmanian devils has prevented fox establishment through interference competition, either aggressive exclusion or predation on denned juveniles. Red Foxes and Tasmanian devils share preferences for den sites and habitat, and are of a similar size. Tasmanian devils abundance is likely to slow, if not prevent, fox establishment.

It is possible that foxes have been present in Tasmania for many decades at sub-detectable levels, and that a degree of ecological release has occurred due to DFTD, with foxes increasing to detectable numbers. The current impact of the Red Fox has been quantified, and it is unlikely that fox numbers are currently at a level to impose a measurable impact.

A decline in Tasmanian devils number may create a short to medium-term surplus of food, for example carrion; ideal for fox establishment. Fox establishment may cause both direct and indirect effects on Tasmanian devils. Direct effects include (reciprocal) killing by then abundant foxes of then rare juvenile devils at dens while the female forages.

Fox establishment may also cause ecosystem disruptions through changes in other species - a feature of foxes on mainland Australia and something that might then also indirectly affect Tasmanian devils. Tasmania has the potential to hold up to 250,000 foxes (based on modelling of habitat preferences and densities in south-east mainland Australian) which could replace most medium- to large-sized marsupial carnivores.

Image: Red foxes have been reported to prey on Tasmanian devils/Other Marsupials.

PERSECUTION:

In the past, persecution of the Tasmanian devil has been very high throughout settled parts of Tasmania, and is thought to have brought about very low numbers at times. Through the 1980s and 1990s, systematic poisoning in many sheep-growing areas (particularly fine-wool with its reliance on merinos) was widespread and probably killed in excess of 5000 devils per year. In the 1990s, control permits were occasionally issued to individuals who were able to argue that Tasmanian devils were pests (e.g. killing valuable lambs).

Current persecution is much reduced, but can still be locally intense with in excess of 500 devils thought to be killed per year. However, this is reducing since devil numbers have declined. While the small amount of current persecution is likely to persist it is unlikely to constitute a major threat unless the Tasmanian devil population becomes extremely small and fragmented.

LOW GENETIC DIVERSITY:

Dr Jones in 2004 found the genetic diversity of Tasmanian devils to be low relative to many Australian marsupials as well as placental carnivores. This was consistent with an island founder effect, but previous marked reductions in population size may also have played a role. Low genetic diversity can reduce population viability, and resistance to disease.

Image: Tasmanian devil (photographer unknown).

Tasmanian devils normally eat birds, snakes, fish, reptiles and insects. Furthermore its not uncommon to witness the species feasting on dead carrion. Female devils will mate with dominant males, who fight to gain their attention. Three weeks after conception, the females ‘can’ give birth to up to FIFTY BABIES, called joeys, although some reports state between 20-30 joeys. These extremely tiny joeys scramble to attach themselves to one of the four available teats in the mother’s pouch. Gestation is around 21 days.

For now the future is uncertain with regards to the Tasmanian devil. The species hosts a large number of natural threats, as well as roadkill accidents, human persecution and (DFTD). For now populations are considered to be generally high, although not that high for the species to qualify as vulnerable, or even near threatened. There are a number of Australian marsupials facing many threats, despite the continent being inhabited at some 10% by humans, or to be precise - 768,685 km2.

While I myself cannot state for certain what the future may hold for the Tasmanian devil - for now based on the large number of threats and continued population declines - its highly likely that come 2026 we’ll be seeing yet another Australian extinction occurring under our noses, and that is the sad reality of life from which our wildlife is facing today.

One thing is for sure though - never underestimate the DEVIL - they’re not called devils for nothing and have a rather cute temper too. Welcome to the planets largest carnivorousness marsupial. The Tasmanian devil

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Master Scientist of Environmental, Botanical & Human Science

Endangered Species Monday | Brachylophus fasciatus.

Endangered Species Monday | Brachylophus fasciatus

This Monday’s (ESP) Endangered Species Watch Post report I document on a rather “undocumented species” of iguana identified back in the 1800’s. (Photographer unknown)

Identified back the 1800’s, and listed as [endangered] the species was originally identified by French Dr Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 1770 – 7 October 1847) who was a French chemist, mineralogist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris.

Dr Alexandre Brongniart was born in Paris, the son of the architect Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart and father of the botanist Adolphe-Théodore Brongniart. He was an instructor at the École de Mines (Mining School) in Paris and appointed in 1800 by Napoleon’s minister of the interior Lucien Bonaparte director of the revitalized porcelain manufactory at Sèvres, holding this role until death.

The young man took to the position a combination of his training as a scientist— especially as a mining engineer relevant to the chemistry of ceramics— his managerial talents and financial acumen and his cultivated understanding of neoclassical esthetic. He remained in charge of Sèvres, through regime changes, for 47 years.

Commonly known as the Fiji Banded Iguana, Lau Banded Iguana, South Pacific Banded Iguana, or Tongan Banded Iguana the species is unfortunately endangered and nearing extinction within the wild. A reptilian, and member of the iguana family the species has been placed within the order of (Squamata).

Within the past TWO DECADES the species has undergone a decline of some 50% throughout its range. Furthermore species declines are still ongoing with no apparent let up neither, (threats have been noted as significantly severe and widespread).

Without conservation intervention, the degradation observed during the last 20 years is predicted to cause further declines over the next 20 years that approaches 80% and potentially will be found to be even higher with further population analysis. Basically unless conservation efforts are improved or continue then we will lose the species very quickly.

Image: Fiji Banded Iguana (Credits: Robin Carter)

Now to some humans this may not seem much to worry about. However let me ask you this. Have you experienced a rather large number of flies bothering you, mosquitoes, insects, and general bugs wreaking havoc with your everyday life? If the answer is “yes”, then maybe you need to be paying attention to my articles. Reptiles loves flies, and without reptiles there will be more flies.

Endemic to Fiji, the species has recently been introduced to Tonga. Among all the islands surveyed for the presence of Lau Banded Iguana, only on the two Aiwa Islands were enough lizards found to estimate a population size, this was estimated to number less than 8,000. That population size is concerning (especially when we take into consideration life span, gestation, and threats). 8,000 can soon turn into 1000 in under five years.

Although there is no official “population size estimates”, its believed from census reports (which I myself do question), within the past 35-40 years the species has undergone (as explained above) a decline of 50%. Discussions with island residents indicate that on most islands the iguanas are now more rare than they had been in the recent past.

Most islands in the region are now inhabited and iguanas were generally found in degraded forests or remnant forest patches, but not in proximity to villages or gardens. Surprisingly, among the uninhabited islands surveyed only one was found to have iguanas present, but this is likely due to the abundance of cats present on the iguana-free islands. It is known that local residents intentionally translocate kittens to these uninhabited islands for rat control.

In summary, a total of 52 islands in the Lau Group and Yasayasa Islands were visited between 2007 and 2011 and iguanas were detected or reported from only 11 islands, with an additional report from one island that was not visited. The sheer fact we only have on ELEVEN ISLANDS instead of FIFTY TWO Fiji Banded Iguanas, just goes to show we have serious problems here that need addressing before its to late.

Iguanas were abundant on only three islands, the two neighbouring Aiwa Islands and Vuaqava, all of which are uninhabited. Goats have recently populated all three of these islands and Vuaqava has a seemingly large cat population (which could be a threat). Most of these 53 islands should have had resident iguana populations. For example, two islands with historic populations, Moce and Oneata, were described by the Whitney Expedition and have since been extirpated. Given these results, it appears that iguanas could be remaining on about 20% of the islands in the region and are abundant on only 5%.

“SO WHAT ARE THE THREATS?”

The current band at which the Fiji Banded Iguana sits in (in regards to known population levels) is 8,000 120,000 mature individuals. Now that doesn’t mean we have 8,000 or 120,000 mature individuals. The current band basically means what we have “assumed the population” based on very sketchy and rough census estimates. What we do know, is that from the last census conducted only 8,000 were eye balled (meaning that 8,000 were physically witnessed). Further census counts are underway.

Lau Banded Iguanas are sometimes locally kept as pets, and this was observed on three different islands during surveys in 2011. Historically, these iguanas would have been a local food source, similar to the larger extinct species (Lapitaiguana and B. gibbonsi) in the region, but there are no recent records of human consumption. The black market trade in Brachylophus does not include this species and is unlikely to be a threat in the future as its remaining localities are very remote.

Black Rats (Rattus rattus) and feral cats (Felis catus) are the main mammalian predators threatening the persistence of iguanas and are capable of causing local extinctions in a relatively short time period. Fortunately, mongoose has not been introduced to the Lau Group yet, and maintaining it free of them is an important biosecurity issue. On a few islands, free-roaming domestic pigs (Sus scrofa) were observed to cause major disturbance in small forest patches, turning large areas to bare mud that is no longer suitable for iguana nesting.

Even in the absence of goat herding, forest burning is widespread and is increasingly one of the biggest threats to iguana habitat and their persistence. Continued deforestation on the small islands where Lau Banded Iguanas remain is predicted to cause additional local extinctions over the next 40 years. In particular, on the large islands of Lakeba and Vanua Balavu where iguanas should have been numerous, there has been significant forest loss through deforestation, burning, and fragmentation.

Image: Fiji Banded Iguana (Photographer unknown).

Additional threats to the native forests include further development of urban and village areas, plantation agriculture, and logging. In particular, harvesting Vesi Tree (Intsia bijuga) for use in traditional carving on several islands (for example, Kabara) has significantly reduced the native forest. Forest conversion to Caribbean Pine plantations is also significant, especially on Lakeba.

Proposed development of tourism resorts, on the smaller islands in particular, has significant impacts on these habitats, possibly leading to losses of entire iguana populations as has been observed elsewhere in Fiji. Finally, proposed new cruise ship routes to the remote Lau islands will require construction of new infrastructure and is likely to be a source of invasive species from Viti Levu unless strict biosecurity measures are enforced.

The impact of the recent introduction and spread of the invasive alien Common Green Iguana (Iguana iguana) in Fiji are not yet known for this species but have been shown to have significant detrimental effects everywhere they have been introduced. Eradication for this invasive now appears unlikely, and it is possible the Green Iguana will continue to spread to other well-forested islands despite eradication efforts. Green Iguanas are vastly more fecund and aggressive than native iguanas and may have significant effects on remnant small island populations.

At minimum, this introduction has caused considerable confusion in the local education programmes aimed at protection of Banded Iguanas versus eradication of the Green Iguanas, since juveniles of the latter appear superficially similar. The northern Lau Islands are very close to Qamea where the Green Iguana was first introduced and are at high risk of invasion.

Irruptions of invasive alien Yellow Crazy Ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) are known to occur on many of the southern Lau islands. Even though these ants were introduced to Fiji over 100 years ago, it is not understood what causes populations to periodically irrupt in huge numbers on some islands. When Crazy Ants irrupt, the entire ground surface, shrubs, and trees are entirely covered with ants and it has been observed that native skink and gecko abundance drops greatly during this time.

The impact of aggressive ant irruptions on iguana reproduction and recruitment is not known, but is likely to suffer similarly to other lizards. Lau Banded Iguanas are sometimes locally kept as pets, and this was observed on three different islands during surveys in 2011 (as explained above).

Historically, these iguanas would have been a local food source, similar to the larger extinct species (Lapitaiguana and B. gibbonsi) in the region, but there are no recent records of human consumption. The black market trade in Brachylophus does not include this species and is unlikely to be a threat in the future as its remaining localities are very remote.

Listed as endangered, the current future is not as yet known. However what we do know is that the Fiji Banded Iguana does not inhabit the ground it once did. Threats are wide, and the species has undergone a large population decline.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical and Human Science.

Endangered Species Monday: Papilio homerus |Extinction Imminent.

Endangered Species Monday: Papilio homerus

This Mondays (Endangered Species Post) E.S.P, I document again on this stunning species of swallowtail butterfly. I last documented on this amazing species of butterfly two years back, unfortunately conservation actions that were ongoing back then still don’t seem to really be improving the current status of the largest swallow tail butterfly in the Western Hemisphere. Image credited to Dr Matthew S. Lehnert.

Despite the species nearing (complete extinction) within the wild, with a possible extinction likely to occur soon, biologists and conservationists are doing all they can to improve the current status of this beautiful insect, we can only hope for the best, or that the Jamaican Government increases further protection for the species, thus earmarking funding for conservation teams on the ground to preserve our largest Western Hemisphere species of swallowtail.

Endemic to Jamaica, the species was first discovered by Professor Johan Christian Fabricius (7 January 1745 – 3 March 1808) who was a Danish zoologist, specializing in “Insecta”, which at that time included all arthropods: insects, arachnids, crustaceans and others. He was a student of Professor Carl von Linnaeus, and is considered one of the most important entomologists of the 18th century, having named nearly 10,000 species of animals, and established the basis for the modern insect classification.

Professor Johan Christian Fabricius first identified and documented on P. homerus back in 1793. The common name for this swallowtail butterfly is known as the Homerus Swallowtail, which is listed as [endangered]. Back in 1983 the species was first listed as [vulnerable]. Then from 1985-1994 the species was re-listed as [endangered]. Evidence shows from 2007 we almost lost the species, of which conservation press and media pleaded with the public for help, which did in a way increase awareness. Sadly we need more awareness on and about this butterfly.

The specie hosts a wingspan of some fifteen centimeters, the Jamaican swallowtail is said to be the second largest swallowtail of its kind on the planet, with the African swallowtail alleged to be the largest. The species can only be located within the forests of Jamaica, of which habitat loss remains the largest yet significant threat associated with this species of swallowtail butterfly, butterfly collecting is alleged to be the second largest threat. Parasitic wasps also pose a large threat to the P. homerus too.

Back in the 1930’s P. homerus was considered to be somewhat common throughout Jamaica, however, regrettably the species can now only be located within the Blue and John Crow Mountains in eastern Jamaica. Population count is [estimated to be no fewer than fifty individuals], which theoretically makes this super stunning butterfly one of the planets most threatened species of insects.

P. homerus is included on the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species wild flora and fauna (Cites), of which (all domestic and international trade of this species is strictly illegal). Collection for display and trade is illegal, and finally destruction of the swallowtail butterflies habitat is furthermore strictly ‘forbidden’.

It has been suggested that the species could/may ‘benefit from captive breeding’, more data on this subject can be located hereto http://www.troplep.org/TLR/1-2/pdf005.pdf The caterpillars feed exclusively on Hernandia jamaicensis and H. catalpifolia; both of which also are endemic to Jamaica.

The Giant is a peaceful lover of a quiet habitat and is normally found in areas that remain undisturbed and unsettled for the most part, although due to destruction of its habitat can rarely be found at some cultivated edges of the forests on the island. P. homerus primary and favorite residence is usually the wet limestone and lower montane rain forests, however, it is now isolated to only 2 known locations on the island of Jamaica. The reproduction habits are not well known but like most of its fluttering cousins, it feeds on leaves and flowers where it also breeds and lays eggs that develop on the host plants.

P. homerus future remains critical, and its quite likely that we’re going to see yet another extinction occur sometime very soon. As much as I hate to say this, I do honesty believe that a complete wild extinction may occur in no fewer than 1-2 years (if that). However I believe based on the current populations, data, and habitat destruction, that extinction will occur sooner than that. I am not aware (as explained) of any captive breeding programmes, which if such projects are not undertaken now, we’ll see the species gone for good in under a year.

Image: P. homerus caterpillar.

Thank you for reading, and please share this article to create more awareness relating to the Jamaican swallowtail, and lets hold our breath and pray to almighty God that somewhere out there, wherever God may be, a miracle may occur.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Follow our main Facebook page here: https://www.facebook.com/InternationalAnimalRescueFoundationAfrica/

International Animal Rescue Foundation and Environmental News & Media are looking for keen, enthusiastic, environmental and animal lovers to write alongside us. We do not pick sides, and show both sides to every-story. We like to take a more middle stance, rather than a one-sided stance. If you would like to spare an hour of your time, per week, voluntarily writing for us, or your own environmental/animal welfare related issue please contact us via the contact box below.

Please note that we have since moved our main communications website to a new and more professional server that will be hosting everything from real life news, real time projects, world stories, environmental and animal rescues and much more. International Animal Rescue Foundation is a 100% self funded environmental company. While we don’t rely on donations, you can make a donation to us via our main Anti Pet & Bush Meat Coalition organisation page.

Have a nice day.

Endangered Species Friday: Solenodon paradoxus | Extinction is Imminent.

Endangered Species Friday: Solenodon paradoxus

This Friday’s (Endangered Species Post) E.S.P, I touch up again on the Hispaniolan Solenodon, scientifically identified as Solenondon paradoxus. Image credit: Mr Jose Nunez-Mino. My reasons for re-documenting on this species is primarily due to my belief that extinction is now most certainly imminent. Therefore for that reason I think its critical that we all make as much noise as possible for this little one due to is importance within the theater of conservation, and because its one of very few mammals that do actually host a venomous side to them.

Written by Dr Jose C. Depre; Botanical and Conservation Scientist.

Solenondon paradoxus was identified back in 1883 by Dr Johann Friedrich von Brandt (25 May 1802 – 15 July 1879) was a German naturalist. Brandt was born in Jüterbog and educated at a gymnasium in Wittenberg and the University of Berlin. In 1831 he was appointed director of the Zoological Department at the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences, where he published in Russian. Brandt encouraged the collection of native animals, many of which were not represented in the museum. Many specimens began to arrive from the expeditions of Severtzov, Przhevalsky, Middendorff, Schrenck and Gustav Radde.

Listed as (endangered) the species is endemic to the Dominican Republic; Haiti. Back in 1965 the species was re-located and reassessed of which scientists agreed the species ‘required watching due to concerns relating to low population levels’. Unfortunately, and despite the species then being known as severely threatened, from 1982-1996 the Solenondon paradoxus was re-listed as (endangered), now nearing almost complete extinction within the wild. It is without a doubt that we may be seeing this stunning “slotted tooth mammal” extinct within the next two to three years. The name Solenodon means ‘slotted tooth’ of which this insectivorous mammalian is known to be (venomous).

Population levels within the wild have been identified as (severely fragmented), and a population decrease within the species native wild has been ongoing since the early 1980’s, the mammal-like-shrew is considered to be extremely rare. Furthermore within Haiti the species “could be considered as critically endangered” due to an isolated population that covers only 100 kilometers square. Habit loss and persecution are the primary threats associated with the species.

The Haitian solenodon as the species is commonly known to the locals resides mainly next to plantations, forest and brush country. The species leads a mainly nocturnal life where it hides among rock clefts and under large stones, dark caves or hollow trees. Diet atypically consists of insects, but mainly spiders which the species digs from the ground and leaf litter. Small frogs and reptiles are also known to be part of the mammals diet. Haitian solenodon will use its long snout to sniff out food even buried deep into the ground then its powerful claws to locate food via burrowing which are about 2-4cms long, a venom will if required be administered to much larger prey.

The species is relatively social and does not live a solitary life, its been noted that the species prefers to live within groups of 5-8 within underground burrows, which is almost similar to the European moles behavior. Gestating females will normally give birth to 1-2 young and no more, young will always be born within the main family burrow. Young will remain with their mother for approximately seven to eight months, from which after maturity they are left to fend for themselves, however its been documented that the young and parents will ‘sometimes socialize and live together’.

Currently under Dominican Republic law the species is protected under the General Environmental Law of 64-00. A recovery plan was published back in 1992 aimed at improving surveys, and management of the National Park Pic Macaya followed up with educational plans to help reduce species populations decline. A further implementation within the protection plan was to decrease exotic animal sales of the mammal and address these main issues wildly over the animals range.

Unfortunately since 1992 nothing “hard hitting” has been put into practice, and its quite likely that should anyone of the actions now be played out - its most likely to have no affect whatsoever due to the species now bordering complete extinction within the wild. However I myself do believe that we can only but try create as much noise as possible, applying pressure where needed thus forcing the Haitian Department of Environment, and Government to now protect this specie and implement whatever actions necessary to preserve this mammalian and its current habitat.

Major Threats

The most significant threat to this species appears to be the continuing demise of its forest habitat and predation by introduced rats, mongoose, cats and dogs, especially in the vicinity of human settlements. In Haiti persecution and hunting for food is a major threat, and there is devastating habitat destruction also occurring.

Venom Warning

Despite the fact humans and other predators prey on the animal, and the fact this animal is rather small, Solenondon paradoxus does indeed pack a small “unknown venomous punch”, and you’d not really want to be bitten by this little one. I cannot emphasize the importance of wearing “protective clothing in the way of gloves” should you come into contact with this animal. Venom is administered in more or less the same manner as snakes administer their venom (not poison). Please note there is a very big difference between (venom and poison).

The solenodon is particularly fascinating because it delivers its poison just as a snake does—using its teeth as a syringe to inject venom into its target. Not a lot is known about these unusual mammals. There are only two solenodon species: One lives on Cuba and the other on Hispaniola (home to Haiti and the Dominican Republic). At night when the species goes in search of food venom would typically be administered to more larger prey such as frogs, and smaller reptilians that the animal also feeds on, despite the animals diet mainly consisting of insects. While the venom is not “considered dangerous to humans” there is actually no hard hitting evidence that its venom is or isn’t dangerous.

The reason I state that, is because most handlers within zoological gardens do actually wear gloves in order to protect themselves from being bitten. So theoretically speaking it would be considered safe to say that while little is known about the animals venomous side - please wear gloves should you come into contact with the animal until more data can be located on the animals venom Etc.

There remains no current data in relation to how many mature and non-mature solenodon individuals there are within the wild, furthermore little is known about life expectancy, however locals have stated local populations can/have lived for up-to 5-7 years.

I am unsure what the future holds for this rather peculiar animal, its one of very few mammals that do actually have the ability to administer a venomous bite via its salivary glands too. The Hispaniolan solenodon represents a remarkable amount of unique evolutionary history, diverging from other living mammal groups some 75 million years ago and before the extinction of the dinosaurs. Conservation efforts don’t seem to be improving the animals population levels, however I am told that conservation actions have been planned. Will they work though now is another story.

The clock is ticking fast for this little one…While I want to believe that we can do something I do believe that its probably too late. Therefore I predict that my next document on this species will be informing the general public of its wild extinction. That would be considered quite sad to be fair regarding my look at things. Check out the video below.

“EXTINCTION IS IMMINENT”

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre. PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental, Botanical and Human Science.

Follow me on Twitter: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Donate via our Facebook button: https://www.facebook.com/Anti-Pet-and-Bush-Meat-Coalition-474749102678817/app/117708921611213/

Sign up here: https://www.facebook.com/Anti-Pet-and-Bush-Meat-Coalition-474749102678817/app/100265896690345/

Whatever you do may seem insignificant to you, but its most important that you do it!

Endangered Species Monday: Papustyla pulcherrima | Special Report.

Endangered Species Monday: Papustyla pulcherrima

Manus Green Tree Snail - Very first invertebrate to be listed on the Endangered Species Act of the United States of America (2015) Endangered Species Post Special Report.

This Monday’s Endangered Species Post (ESP) I take a wee glimpse into the life of the Green Tree Snail, also commonly known by Papua New Guinea’s natives as the Manus Green Tree Snail. Image Credit: Stephen J. Richards.

Identified by Professor Rensch 1931, Rensch was born on the 21st January 1900 in Thale in Harz and died on the 4th April 1990 in Münster, (Germany), Professor Rensch was an evolutionary biologist, zoologist, ethologist, neurophysiologist and philosopher and co-founder of the synthetic theory of evolution. He was professor of Zoology and Director of the Zoological Institute at the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster. Together with his wife Mme Ilse Rensch he also worked in the field of Malacology and described several new species and subspecies of land snails.

The Manus Green Tree Snail is identified as Papustyla pulcherrima commonly known as the Emerald Green Snail. From 1983-1994 this particular species of snail was considered (extremely rare). Back in 1996 when scientists managed to again finally catch up with this stunning little mollusk, the species was then listed as (data deficient) of which to date there remains little information about this (rare) but beautiful snail.

P. pulcherrima is endemic to the Papa New Guinea northern island of Manus of which the species is listed as (near threatened), and has also been reported on the adjacent Los Negros Island. Environmental scientists have confirmed from villagers on the main Manus Island that the species is not located anywhere else. However there are some sketchy reports that the species “may be located on surrounding islands”, however there is no evidence to back these claims up.

Environmental scientists have confirmed for now that the species is located in only 12-13 areas of the Manus Island[s]. Further reports have confirmed that mature individuals are on the decline (which if not controlled could evidently see the species re-listed as vulnerable or endangered). The Manus Green Tree Snail is not believed to be living within fragmented zones. The species is restricted to forest and low intensity garden ‘type’ habitat. Declines have been noted within all 12-13 identified habitats on the Manus Island and adjacent Los Negros Islands. Population history is pretty much undocumented although has been shown to be slowly declining.

Image: Manus Green Tree Snail.

Back in 1930 when Professor Rensch identified the Manus Green Tree Snail, locals soon began collecting the species for trade thus seeing the mollusk now nearing endangered listing. Demand for the Manus Green Tree Snail has now drastically increased threatening the species furthermore. Locals continue to collect this rather unusual colored species shell for use within the jewelry trade. There are now “very serious concerns” that trade may eventually push the species into extinction.

Due to mass trade exploitation the Manus Green Tree Snail is the very first invertebrate to be listed on the Endangered Species Act of the United States of America. International trade has been controlled by export permit since 1975 under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) appendix II. Unfortunately this is not stopping locals from harvesting the species, and trade is still continuing despite it now a criminal offence under United States and some international laws.

“Overexploitation threatens the Manus Snail”

Market sales data collected from the Lorengau market, over a six day period suggest that annual sales at the market may approach 5,000 shells. Investigations by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) reveal that large quantities of shells are still being attempted to be exported out of the country. Online searches revealed the sale of the shells, often marketed as antiques, occurring in open forums and internet market places based in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States of America (USA). International Animal Rescue Foundation has ran numerous traces online of which located yet again Ebay as being a number one trading site of the “threatened species”, please view the image below and click the image link that’ll direct you to that site.

“EBAY JAPAN IS A HOTBED FOR ILLEGAL TRADE OF THE MANUS GREEN SNAIL”

International Animal Rescue Foundation’s External Affairs Department and the Environmental Cyber Crimes Unit located many a sites trading the Manus Green Tree Snail’s shell which is illegal under some trade law, unfortunately the Ebay site listed above, located within Japan is one of many more that are trading (despite the species nearing extinction).

I.A.R.F’s Environmental Cyber Crimes Unit have since filed a complaint with Ebay, providing all the relevant data to now remove these species from their sites, however its likely to prove negative as the trader could very well state they harvested or purchased the shells before international laws were drafted. Furthermore a trace of the owner that owns this site above which is in violation of the United States and Cites laws (is located within the United States). So in regards to enforcement, breaking this link is going to be somewhat of a tough cookie. Further trade was witnessed here via what we can only believe is alleged “antiques”.

Further trade all of which is illegal has been recorded hereto - this site linked back to a Mr Rob West of 121 Henderson Road, Sheldon, Brisbane, Queensland 4157 Australia, Telephone: 610732061636. Mr West from Brisbane categorically states that he doesn’t own a shop, and is a one man band, yet clearly this link states otherwise. Further evidence revealed antique trade conducted on the Ebay site, see in the image below (illegal under United States law).

Click the image link below to view more.

“Illegal to trade under the Endangered Species Act of the United States of America”

The environmental wildlife crimes investigation team linked to TRAFFIC and Cites stated:

It is possible the avoidance of conventional nomenclature is an attempt to avoid detection by authorities. In some cases, sellers on internet market places were based in CITES signatory countries (including: Australia, Italy, New Zealand, Singapore and USA) while others were not (e.g. Taiwan). Currently, volumes of shells on sale in such online market places appear low, suggesting that the existing controls on international trade maybe adequate. However, given that the online prices of shells were often orders of magnitude greater than market prices on Manus Island, vigilance will be required to insure that illegal international demand does not fuel a resurgence in snail collection.

Despite the massive trade on Manus Green Tree Snails online and within open Asian markets, its literally impossible to determine if this trade will eventually lead to the species being pushed into extinction. However it MUST be noted that there are currently only 12-13 identified habitats that the snail currently inhabits. And based on traces online conducted by the I.A.R.F’s External Affairs Department - trade is most certainly “out of control”, and not as Cites has reported (2012).

The shell of this species is a vivid green color, which is unusual in snails. The green color is however not within the solid, calcium carbonate part of the shell but instead it is a very thin protein layer known as the periostracum. Under the periostracum the shell is yellow.

MAJOR THREATS

The Manus Green Tree Snail is mostly threatened by habitat destruction through forest clearance: logging, plantation development (especially rubber) and to a lesser extent road developments. Increasing human population growth and an increasing cultural demand for deriving cash incomes from the land will likely see the rate of forest degradation increase in the future. Harvest occurs when trees are felled as part of traditional shifting cultivation and the snails, typically found in the canopy, suddenly become exposed. Such harvesting is not uncommon but it is likely to be of lower significance than the longer term habitat degradation caused by such agricultural practices.

While harvest for illicit international trade is occurring, the volumes are not “allegedly” thought to be large compared to historic rates, although they may approach levels seen in the legal domestic trade. However, given that the prices of shells internationally are often orders of magnitude greater than market prices on Manus Island, vigilance will be required to insure that illegal international demand does not fuel a resurgence in snail collection.

Notable deposits of gold have been found in central Manus and a mine operation will likely result in the next decade although no details of the plan have been released (as of 2014). The forests of Manus Island were badly affected by the 1997-1998 El Niño which resulted in a prolonged drought. Should climatic change result in increased rates of similar conditions this may constitute a future threat to the snail species, however, current predictions suggest that future incidence of drought in Papua New Guinea will decrease (Australian Bureau of Metrology and CSIRO 2011).

Despite the reassurances from Cites, WCS and the local wildlife organisations - evidence clearly points to large scale online trade legal and illegal. Furthermore there is no telling if shells online are antique or smuggled from the Manus Islands which is very concerning.

Manus Green Tree Snail is the first such snail to be listed on the threatened list of endangered species (USA). Research also explains to us that its likely the species will be plundered into extinction - very soon. Enjoy the video.

Thank you for reading, and please be most kind to share to create awareness and education.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Environmental & Human Science

Donate by clicking the link below:

https://www.facebook.com/Anti-Pet-and-Bush-Meat-Coalition-474749102678817/app/117708921611213/

Sign up here to our A.P.B.M.C news feed below here:

https://www.facebook.com/Anti-Pet-and-Bush-Meat-Coalition-474749102678817/app/100265896690345/

Follow me on Twitter here:

https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Sources:

IUCN, WWF, CITES, WCS, Ebay, Wikipedia, Australian Bureau of Metrology and CSIRO

Endangered Species Monday: Tremarctos ornatus

Endangered Species Monday: Tremarctos ornatus

This January’s (2016) Endangered Species Watch Post is dedicated to the Tremarctos ornatus, commonly known as the Andean Bear or Spectacled Bear. The species was identified by Dr Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier back in 1825. Dr Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier lived from (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the “Father of paleontology”. Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century and was instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in comparing living animals with fossils.

From 1982 to 1996 the Andean Bear has been listed as (vulnerable), of which its main threats are habitat loss and major poaching for the animal parts trade. Within the past thirty years populations have declined by a staggering 30% which qualifies the bear as being listed as (vulnerable). Habitat loss continues at a rate of 2-4% per year, which as yet doesn’t look set to decline. Furthermore identified threats do not look set to decrease anytime soon which could see this stunning animal pushed into extinction very soon.

Poaching is one of the main problems that can be controlled if (anti poaching enforcement) is increased within the bears habitat, unfortunately this is easier said than done. Furthermore, continued habitat destruction and illegal logging will see forest tracks opened up within the bears natural habitat, thus allowing poachers to walk freely into the bears home environment, thus seeing poaching occur. Anti poaching enforcement is a must, and needs to be taken seriously by all international (non-governmental organisations) that are working to sustain this animals welfare, and habitat.

Endemic to Bolivia, Colombia; Ecuador; Peru, and Venezuela, populations of the Andean Bear are now known to be decreasing rapidly, however populations are not reported to be (fragmented). Back in 1998 it was estimated by Dr Peyton that there was a mere 20,000 Andean Bears remaining. A 2003 survey, however estimated that there was in between 5,000 to 30,000 Andean Bears remaining. Andean Bears are now commonly located within the eastern Andes of which bear populations exist from the snowline down to 300 m asl in the Tapo-Caparo National Park in Venezuela. Andean Bears can also be located at high altitudes in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Columbia.

Andean Bears are “omnivores”, meaning that they feed exclusively on plant matter, fruits, bark and occasionally will consume meat of other animals, the bears preferred diet though is reported to be species of flora from the Bromeliaceae and Arecaceae. Activity patterns range from strictly diurnal for wild bears in Bolivia to mixed diurnal and nocturnal for reintroduced bears in Ecuador.

“EXTINCTION BY 2030 IS POSSIBLE”

As food is available year-round in all parts of their range, Andean bears do not hibernate. Based on the first few individuals of this species to be monitored using ground telemetry in Bolivia and Ecuador, home ranges overlap to a high degree and minimum home range sizes vary from 10 to 160 km² (although these are underestimates, as the bears were regularly out of range of radiotelemetry in both studies).

The Andean Bear stands at around 5ft to 6ft tall, and weighs in at around 220, 330lbs. The markings on the Andean bear’s face, neck and chest are exactly like human finger prints (unique to each and every individual Andean Bear). Andean bears are very timid and shy and prefer to live in isolated cloud forests, of which they are “mainly nocturnal” however will at times feed, live and socialize in daylight (although this is considered rare). Favorite foods are cacti, berries and of course honey.

Andean bears are quite typically solitary animals, and will only be seen in pairs during mating season. Females normally give birth to (1-2 cubs), cubs are normally mobile after one month, however will remain with their “mother” for up to eight months, mothers will often be seen with little cub hitching a ride on the back on the mothers back. Population studies state today that there may be no fewer than 3,000 Andean bears in the wild., which if true could soon see the species nearing extinction by 2030.

ANDEAN BEAR THREATS

Habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching, and the lack of knowledge about the distribution and status of the Andean Bear are the principal threats to this species. Much of the range of the Andean Bear has been fragmented by human activities, largely resulting from the expansion of the agricultural frontier. In some areas, mining, road development and oil exploitation are becoming a greater menace to Andean Bear populations as well as to local communities, due to land expropriation, loss of habitat connectivity, and water and soil contamination.

Many Andean Bear populations are isolated in small to medium-sized patches of intact habitat, particularly in the northern part of the range. The situation tends to improve towards the southern range, with some large patches of wilderness still remaining. Nevertheless, human population growth and national development plans throughout the Tropical Andes continue to be an important cause of habitat fragmentation and to threaten the connectivity among remaining wilderness patches.

Poaching is a serious threat throughout the Andean Bear range. Bears are often killed after damaging crops, particularly maize, or after purportedly killing livestock. Also, Andean Bear products are used for medicinal or ritual purposes and at some localities Andean Bear meat is highly prized. Live bears are also sometimes captured and sold.

Human induced mortality endangers the viability of small remnant populations. Lack of knowledge about the distribution and status is a problem throughout the region. In many areas, information about the status of Andean bears is outdated or, particularly in the southern portion of the range, simply non-existent. The absence of knowledge makes it difficult to develop realistic management plans for the conservation of this species, or to monitor changes in its distribution (reflective of changes in population status).

It is without a doubt the Andean Bear is facing “imminent extinction”, and from studies that are being conducted by various organisations including the International Animal Rescue Foundation Brazil, its very likely this animal is going to be pushed into extinction very soon.

Thank you for reasding the first part of this years (2016) Endangered Species Watch Post, and please feel free to scroll through 2014-2015’s posts below via the automatic scroll new feed bar.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M. Environmental & Human Science

Chief Environmental Officer and Director

Donate today and help us continue our worldwide anti-wildlife trade enforcement operation continuing. Please click the DONATE button below.

DONATE BUTTON

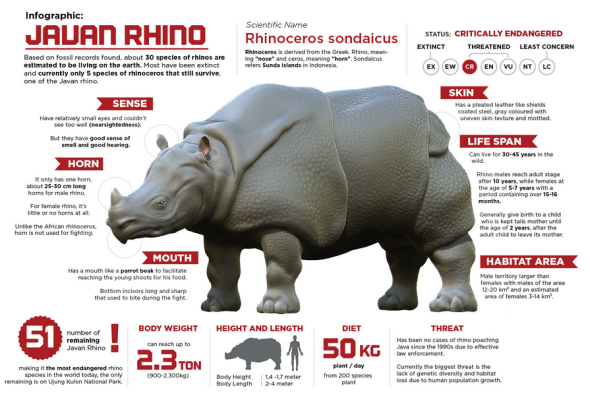

Endangered Species Monday: Rhinoceros sondaicus

Endangered Species Monday: Rhinoceros sondaicus

This Endangered Species Post (ESP) Monday I have decided to touch up on the current fate of the critically endangered Javan Rhinoceros of which scientists this month caught yet another rare glimpse of this rather elusive beast within their still natural habitat. (Pic Javan Rhinoceros)

The Javan Rhinoceros was identified back in 1822 by Dr Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (March 6, 1784 – June 4, 1838) was a French zoologist and author. He was the son of Nicolas Desmarest and father of Anselme Sébastien Léon Desmarest. Desmarest was a disciple of Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart, and in 1815, he succeeded Pierre André Latreille to the professorship of zoology at the École nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort. In 1820 he was elected to the Académie Nationale de Médecine.

Unlike the African black and white rhino, you’d be very lucky to catch a glimpse of this stunning specimen of which is classified as a sub-species of the four extant Rhinoceros and, is nearing complete extinction within the wild. Furthermore the subspecies of the Javan Rhinoceros are all extinct too. Known as Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus, Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus, and Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis the three sub-species went extinct from 1930-2011. Below I have included the “documented dates” of extinctions for the three sub-species to the Javan Rhinoceros.

- Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus (extinction was formally documented from 1999, however this report needs to be backed up with further historical data to pinpoint an exact extinction and location).

- Rhinoceros sondaicus annamiticus (extinction was formally recorded in 2010, however reports state the very last male was located dead within Viet Nam back in 2011).

- Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis (extinction was formally recorded back in 1925).

Please note the Wikipedia article online has confused the (extanct) R. sondaicus with the (extinct) subspecies Rhinoceros sondaicus sondaicus.

From 1965 Rhinoceros sondaicus was considered ‘extremely rare’ within the wild, then from 1986 to 1994 the species was classified as (endangered). Unfortunately from 1996 the species was again re-classified as (critically endangered) and now no fewer than sixty individuals remain within the wild. The last sighting of ‘a’ Javan rhino was I believe on the 18th September 2015 at exactly 17:46 hrs within the Ujung Kulon National Park.

Javan rhino’s did cover quite an extensive area ranging from Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia, Viet Nam, and probably southern China through peninsular Malaya to Sumatra and Java. Sadly the species is now thought to be inhabiting the Ujung Kulon National Park which is located within Indonesia. Further non-viable (all male) and elderly populations are also claimed to be inhabiting a very small area of Viet Nam.

To date the species is now endemic only to Indonesia, however there are said to be few individuals ‘possibly’ remaining within Viet Nam too. I must stress though that there has been no official camera trap sightings or actual eyeball sightings of the species in as many years within Viet Nam of which its likely the species “may have gone extinct”.

Regional extinctions of the current sub-species have occurred within the following countries; Bangladesh; Cambodia; China; India; Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia); Myanmar and Thailand. Reports from the 18th September 2015 have also confirmed that the species has taken some ‘fifty years’ to double in size from (50) to now (60) individuals remaining.