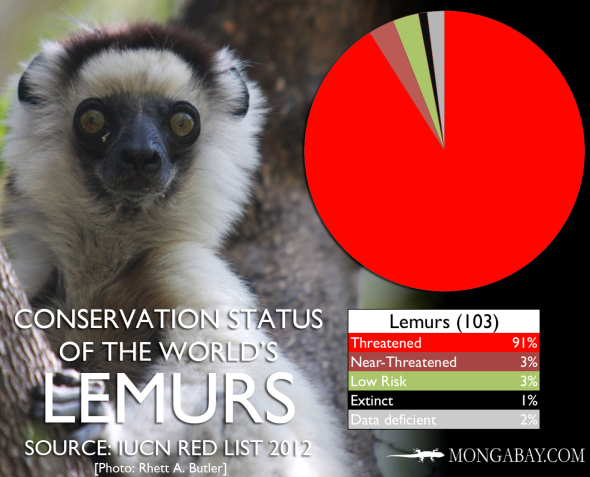

Reports released this June 2014 show a very dark future for Madagascan wildlife, most concerning of all are 80% of temperate slipper orchids and over 90% of lemurs that are threatened with extinction, according to the latest update of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa have been documenting and researching heavily on the grim future that faces our Madagascan wildlife for several years and nothing seems to be really improving if anything habitat fragmentation is drastically increasing, lemur and fauna species habitat is being overrun by farms and herders. It is most likely that the very first mass extinctions are going to occur within Madagascar yet little debate and concern of this issue is being made within the public domain. Only this June did the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) show more concern for threatened species within Madagascar. And when one thought it could not gert any worse did we hear that the worlds rarest bird the Madagascan pochard is likely to be extinct by the end of the 2015 unless drastic action is taken now to preserve the species.

History of Madagascar;

Madagascar a small tropical island situated on the east side of the continent of Africa compromises around 22,005,222 people as seen in the (2012) census, 1994 census showed around 12,238,914 living on the island of which the island host some ten ethnic minority groups. As one can clearly see the problem Madagascar is having like many countries locally and internationally is human over-population that threatens the wildlife and will eventually push many species of animals into extinction due to habitat destructiveness.

Until the late 18th century, the island of Madagascar was ruled by a fragmented assortment of shifting socio-political alliances. Beginning in the early 19th century, most of the island was united and ruled as the Kingdom of Madagascar by a series of Merina nobles. The monarchy collapsed in 1897 when the island was absorbed into the French colonial empire, from which the island gained independence in 1960. The autonomous state of Madagascar has since undergone four major constitutional periods, termed Republics. Since 1992 the nation has officially been governed as a constitutional democracy from its capital at Antananarivo. However, in a popular uprising in 2009 president Marc Ravalomanana was made to resign and presidential power was transferred in March 2009 to Andry Rajoelina in a move widely viewed by the international community as a coup d’état. Constitutional governance was restored in January 2014 when Hery Rajaonarimampianina was named president following a 2013 election deemed fair and transparent by the international community.

In 2012, the population of Madagascar was estimated at just over 22 million, 90 percent of whom live on less than two dollars per day. Malagasy and French are both official languages of the state. The majority of the population adheres to traditional beliefs, Christianity, or an amalgamation of both. Ecotourism and agriculture, paired with greater investments in education, health and private enterprise, are key elements of Madagascar’s development strategy. Under Ravalomanana these investments produced substantial economic growth but the benefits were not evenly spread throughout the population, producing tensions over the increasing cost of living and declining living standards among the poor and some segments of the middle class. As of 2014, the economy has been weakened by the recently concluded political crisis and quality of life remains low for the majority of the Malagasy population.

Again poverty, human overpopulation and increasing cost of living is playing quite a destructive role reducing wildlife on this vast tropical island once filled with an abundant of fauna and flora. While this may be quite a substantial problem so too is poaching on the island. Bush meat trade is thriving that see’s lemurs and critically endangered reptiles killed out of sheer starvation rather than “traditional beliefs”. Vanilla farming that has increased within Madagascar is also hampering conservation efforts with regards to Lemurs. At the beginning of the millennium did we really start seeing environmental destruction regarding the palm oil trade within Asia and Africa. Now we have the vanilla trade that is causing some rather large concerns among conservation groups which was highlighted in full by International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Endangered Species Watch Project.

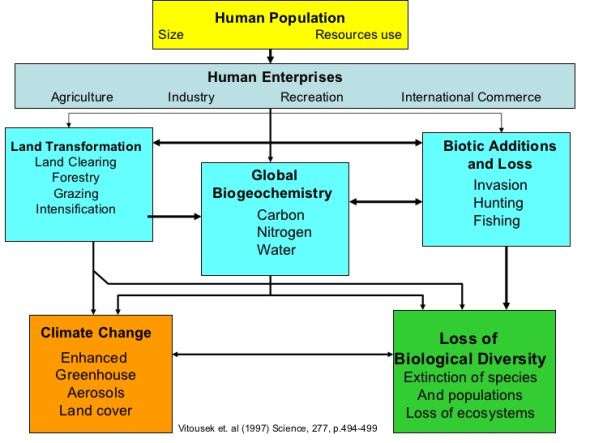

Human overpopulation though remains the main critical factor here that is endangering all of the worlds wildlife. Human overpopulation has increased at at almost exponential rate. With this growth comes an increase in demand for food, water, land, energy and other resources. As human numbers grow within Madagascar so does wildlife diminishes. Biodiversity is the variety of all forms of life throughout an (ecosystem). High rates of extinction are quickly reducing biodiversity especially in areas of the world with high human population and density. As one can clearly see here Madagascar is one prime example. The direct and indirect effect that humans have had on biodiversity can be seen in the graph below.

Madagascar’s natural resources include a variety of unprocessed agricultural and mineral resources. Agriculture, including raffia, fishing and forestry, is a mainstay of the economy. Madagascar is the world’s principal supplier of vanilla, cloves and ylang-ylang. Other key agricultural resources include coffee, lychees and shrimp. Key mineral resources include various types of precious and semi-precious stones, and Madagascar currently provides half of the world’s supply of sapphires, which were discovered near Ilakaka in the late 1990s. The island also holds one of the world’s largest reserves of ilmenite (titanium ore), as well as important reserves of chromite, coal, iron, cobalt, copper and nickel. Several major projects are underway in the mining, oil and gas sectors that are anticipated to give a significant boost to the Malagasy economy.

These include such projects as ilmenite and zircon mining from heavy mineral sands near Tôlanaro by Rio Tinto, extraction of nickel near Moramanga and its processing near Toamasina by Sherritt International, and the development of the giant onshore heavy oil deposits at Tsimiroro and Bemolanga by Madagascar Oil.

Exports formed 28 percent of GDP in 2009. Most of the country’s export revenue is derived from the textiles industry, fish and shellfish, vanilla, cloves and other foodstuffs. France is Madagascar’s main trading partner, although the United States, Japan and Germany also have strong economic ties to the country. The Madagascar-U.S. Business Council was formed in May 2003, as a collaboration between USAID and Malagasy artisan producers to support the export of local handicrafts to foreign markets. Imports of such items as foodstuffs, fuel, capital goods, vehicles, consumer goods and electronics consume an estimated 52 percent of GDP. The main sources of Madagascar’s imports include France, China, Iran, Mauritius and Hong Kong.

Paradise in Peril;

Evidence suggests the first human encounter with Madagascar’s amazing biodiveristy occurred only two thousand years ago. The original settlers probably came by boat from the Polynesian islands or from Africa, bringing with them a farming technique known as “tavy.” In tavy, a farmer cuts a portion of the forest and then burns it, planting rice that is irrigated by rainfall alone. After harvesting the rice, the farmer and his family leave the forest fallow, sometimes for up to 20 years. Once the forest has grown back, many nutrients are again stored in the trunks and foliage, and these are released in the next slash and burn cycle of farming, providing fertilizer for the crop.

This farming practice works well and does not permanently destroy the forest as long as field sizes are small and farmers leave adequate time for re-growth. However, if farmers return to the fallow fields too quickly, as they do when human population densities increase, the soils become exhausted. And if little forest is left in between fields, then there are no parent trees to provide seeds and seedlings to restore the forest. Eventually large areas of forest are transformed into wastelands, upon which nothing can grow—neither rice nor forest. On these areas, farmers pasture a few cattle and continue to burn the grasslands each year, to provide “greener grass” for the cattle.

Sadly, much of Madagascar has been destroyed, by the gradual action of small farmers and herdsmen. Human populations have grown long beyond the point at which these activities can be practiced without permanent destruction. As the forest is destroyed, so is the habitat for Madagascar’s unique plant and animal species. The loss of habitat due to deforestation is the biggest single threat to Madagascar’s wildlife. Although the exact extent of forest loss is not known with certainty, only 10 percent of Madagascar’s forests remain. Also, recent estimates suggest that 1-2 percent of Madagascar’s remaining forests are destroyed each year, and that a staggering 80-90 percent of Madagascar’s land area burns each year.

Although much of the forest destruction may have come about at the hand of the small farmer or herdsman, the causes of environmental degradation are deeply rooted in social, economic, political and historical factors. Madagascar is one of the world’s poorest nations, with a per capita income of approximately $240 per year. About 80 percent of the population are subsistence farmers, many of whom depend entirely on “natural capital” to support their way of life. Yet this way of life is time-limited: as the forest is destroyed so tavy must also end. At the moment, however, many farmers continue to practice traditional slash and burn agriculture because it is their culture, and because they know no other way and have no other means to survive.

Rural people depend on the forest in other ways, and in so doing, pose other threats to this tremendously important resource. In the rainforest, nearby dwellers may use several hundred species of plants and animals for food, shelter, firewood, medicines, fiber, resin, construction, household implements and clothing. Sometimes, as in the case of the most sought-after species, over-collection or over-hunting is now leading to depletion and local extinction of precious biological and natural resources. Indeed, the extinction of several large-bodied lemur species and of the elephant bird (a member of the ostrich family that weighed up to half a ton) within the past several thousand years may have been due at least in part to over-hunting by the early human inhabitants of Madagascar.

Conservation actions under way;

Even with sound conservation projects under way its quite likely that we will lose a staggering seventy to eighty percent of fauna and flora in the years to come. International Animal Rescue Foundation’s External Affairs Conservation Unit has estimated that by the year 2020 its quite likely the majority of Lemur species will have been pushed into extinction this also includes birds and reptilians that depend on the forest as a source of food, refuge and safe haven. External Affairs Unit evaluated forests in the Moramanga region over a period of two years during the seven year research program. They found that deforestation is not only killing off species of both flora and fauna but is opening roads and pathways up to poachers that can gain easy access to once very secluded and non-accessible species of primate and reptilian.

Since the beginning of Madagascar’s Environmental Action Plan, Madagascar has established eight new protected areas totaling 6,809 square kilometers. The country’s new National Association for Protected Area Management has taken over the management of several of the key National Parks for ecotourism (Ranomafana, Isalo, Montagne d’Ambre). As Lisa Dean of CARE International Madagascar said upon the inauguration of the park at Masoala, “The approval of the Masoala National Park … represents a huge commitment by the Madagascar government, done against all odds.” Indeed, for Masoala and many of its other protected areas, Madagascar can be proud of its often path-breaking efforts to develop a plausible, well-founded approach to “parks for wildlife and for people.” Of course, much work remains to ensure that the existing parks and reserves will continue far into the future to provide habitat for Madagascar’s fabulous biodiversity, and the resources for a sustainable future for Madagascar’s people.

Timber mafia and corrupt politicians threaten Madagascar’s wildlife;

While many activists are fighting to stop the slaughter of animals both wild and farmed its now time to focus one’s attention too on the Timber Mafia that is threatening some one hundred species of Lemur and thousands of exotic wildlife specimens endemic to Madagascar. Just how big the timber trade is we will never know. We are aware though that timber is being exported from Madagascar to the mainland continent on the back of large forty four foot wagons through national parks.

Back in 2009 $100m worth of hardwood had been cut down and sold, mostly to China to be turned into furniture. It is believed the same mafia that is ordering such large amounts of hardwood is responsible for the sandalwood trade in India too. The government, which levies a 40% export tax, is accused of not only failing to stop the trade but actively encouraging it. It issued an order back in 2009 authorising the export of raw and semi-processed hardwood. This supposedly related to trees already felled in cyclones, but environmental activists say it has only provided an incentive for more illegal logging.

And yet again China is seen as being the main Mr Big involved in the mass habitat destruction within Madagascar. The EIA - Environmental Investigation Agency stated below;

Voluntary guidelines established by the Chinese government won’t be enough to curb rampant timber smuggling by Chinese companies, putting ‘responsible’ actors at risk of having their reputations tarnished, argues a new campaign by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

Citing a series of recent investigations into illegal logging and timber smuggling involving Chinese enterprises, EIA warned that new guidelines from China’s State Forestry Administration focus too little on timber imports.

“The guidelines are skewed to the operations of Chinese enterprises overseas, and do not regulate importers of illegally-logged timber into China,” said a statement issued by the group.

Jago Wadley, EIA Forest Campaigner, added that the government should establish binding and enforceable laws, rather than voluntary standards.

“As the world’s biggest importer of illegal wood, and in light of extensive irrefutable evidence that Chinese companies are complicit in driving destructive illegal logging and timber smuggling, China needs to move beyond unenforceable voluntary guidelines and take unequivocal actions to prohibit illegal timber,” Wadley said.

Failure to do so could hurt the credibility of Chinese firms trying to sell wood products in markets that have banned imports of illegally sourced timber.

“The guidelines do not offer any reassurances to importers in the US and EU carrying out due diligence that timber products imported from China can be proven to be legal,” said EIA.

“The perpetuation of voluntary approaches to promote legal timber trade maintains an uneven and uncompetitive playing field for the increasing number of responsible companies in China already working to exclude illegal timber from their supply chains. Such companies will find it increasingly difficult to compete with companies trading products made with illegal timber, in ways that structurally penalize legal timber traders. A prohibition on trade in illegal timber is in the interests of those responsible Chinese businesses.”

Species in decline;

There are hundreds of species of plant and animals now verging extinction, nearing endangerment or are listed as vulnerable on the island of Madagascar. The sheer number of lemurs below all of which are listed as (endangered) (critically endangered) or (extinct) just shows how big a problem we have within Madagascar. We ourselves find it quite odd that some African conservation groups are stating that lemur population declines are not as bad as once thought. However if one does there research you’ll locate that out of the listed “endangered” lemurs below you’ll find no more than twelve that are actually of least concern or near threatened. All of the species listed below are verging complete species wipe out in the next ten years unless conservation efforts improve and the Madagascan government do not tackle the timber mafia that is threatening lemur populations all over the island.

Lemurs that could be pushed into complete extinction in under ten years;

Avahi betsileo, Avahi cleesei, Avahi meridionalis, Avahi mooreorum, Avahi occidentalis, Cheirogaleus sibreei, Eulemur albifrons, Eulemur cinereiceps, Eulemur collaris, Eulemur coronatus, Eulemur flavifrons, Eulemur mongoz, Eulemur sanfordi, Hapalemur alaotrensis, Hapalemur aureus, Lemur catta, Lepilemur ahmansonorum, Lepilemur ankaranensis, Lepilemur betsileo, Lepilemur edwardsi, Lepilemur fleuretae, Lepilemur grewcockorum, Lepilemur hollandorum, Lepilemur hubbardorum, Lepilemur jamesorum, Lepilemur leucopus, Lepilemur microdon, Lepilemur milanoii, Lepilemur mittermeieri, Lepilemur otto, Lepilemur randrianasoloi, Lepilemur sahamalazensis, Lepilemur scottorum, Lepilemur septentrionalis, Lepilemur tymerlachsoni, Lepilemur wrightae, Microcebus arnholdi, Microcebus berthae, Microcebus bongolavensis, Microcebus danfossi, Microcebus gerpi, Microcebus jollyae, Microcebus macarthurii, Microcebus mamiratra , Microcebus margotmarshae, Microcebus marohita, Microcebus mittermeieri, Microcebus ravelobensis , Microcebus sambiranensis, Microcebus simmonsi , Mirza coquereli , Mirza zaza, Large Sloth Lemur - Palaeopropithecus ingens (extinct), Phaner electromontis, Phaner pallescens, Phaner parienti, Pristimantis lemur, Prolemur simus, Varecia rubra, Varecia variegata

Out of the listed lemur species above only several species thus far has gone extinct - The extinction of Palaeopropithecus ingens and other related (genera) commonly known as the sloth lemur should be quite a clear message to environmental groups and advocates helping lemurs and other animals of what to expect in the near future when seeing vast declines of wildlife. Again it is believed that “human overpopulation” was to blame for several of the Palaeopropithecus going extinct.

When Palaeopropithecus went extinct is not exactly clear, however scientists have suggested that it could be as recent as about five hundred years ago (anywhere from 1300 to 1620AD). The reason behind the extinction of the several species of Palaeopropithecus has been attributed to the presence of humans to the island of Madagascar, the earliest evidence of which dates back to 2325±43 yr BP.

Scientists have found fossils of Palaeopropithecus that appeared to have cut marks in them, suggesting flesh removal with a sharp object, indicating that the species was hunted by the earliest colonists to the island of Madagascar as a source for food. The first evidence of the early human butchery to Palaeopropithecus was found by Hon. Paul Ayshford Methuen, in 1911, who traveled to Madagascar expressly to collect bones of the extinct lemurs for the Oxford Museum.

The slow locomotion habits of Palaeopropithecus likely made them an easy target for their human predators, who would consume them for food, as well as use the bones for tools. The introduction of humans to Madagascar brought change to an island that had yet to experience the lifestyles of human beings.

Introduction of man-made charcoal and fire to the island caused considerable damage to the forests where Palaeopropithecus lived and bred. In addition the slow reproductive habits of Palaeopropithecus probably attributed to their swift and sudden extinction.

Hunters often state on in our public forums that hunt only for food that they are disgusted by trophy hunters that place species in danger and rarely benefit any conservation project. However it should be stated now that all hunting even for food can endanger any species of which the proof is quite clear above.

Picture drawing of the Palaeopropithecus ingens can be seen below for your information;

Palaeopropithecus ingens - Officially Extinct

The main principal threat that is associated with the majority of lemurs can be viewed below;

The principal threats are habitat loss and hunting. Due to their large size and evident need for tall primary forest, these animals are particularly susceptible to human encroachment and, sadly, hunting and trapping for food still takes place. Furthermore, because remaining populations are concentrated, they may be threatened by the frequent cyclones (hurricanes) however this threat is mainly to the lemur species that live on the coastal ridges of Madagascar and high exposed mountainous ranges. The range of lemur species has also recently been heavily impacted on by the very rapid upsurge of illegal logging after the political events of early 2009, in addition to fires.

Poaching;

Poaching seems to be the second largest thereat to all African animals as we know it. If its not the Rhinoceros or Elephant on the continent of Africa we now see many new and old world species of primate poached for bush meat trade, traditional medicine, garments or witch-craft. We must also remember too that animals are not the only species under threat from poachers. Tropical plants are being ripped from their natural habitat then sold on at very high prices on the black market. International Animal Rescue Foundation France located over a dozen sites online that are peddling threatened species of flora.

Poachers are threatening the survival of the northern Madagascar spider tortoise, which only lives along a narrow strip of the island’s coast. The animal has disappeared from swathes of its habitat, taken by collectors to supply the exotic pet trade.

Wild numbers of the tortoise may have already fallen by 90%, say scientists who have just surveyed its population. The problem continues to worsen due to political instability in the country, which makes it easier for smugglers.

The Madagascar spider tortoise is one of the smaller species of tortoise, and is distinguished by the intricate spider web patterning on the shells of adults. Hence its scientific name Pyxis arachnoides. It occurs as three distinct subspecies, each of which has a slightly different shell shape and lives in a different part of the coastal spiny forests within southwest Madagascar.

However, the tortoise’s appearance is also its downfall.

A new survey suggests that the northern Madagascar spiny tortoise (P. a. brygooi) is now extinct across 50% of its former historical range, with huge numbers being collected to supply the international trade in exotic pets.

Trade in the species is banned, but thousands of the animals are still being smuggled out of the country illegally, says Ryan Walker, a senior wildlife biologist at Nautilus Ecology based in Greetham, Rutland, UK. Walker, who is also a member of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, conducted a survey in March covering all the whole range where the tortoise was once thought to live.

Together with biologists from the Open University in the UK, the IUCN specialist group and the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar, Walker searched 60 sites in detail for wild spider tortoises, recording their occurrence and population density.

He presented the results this month to the Turtle Survival Alliance Meeting in St Louis, US and is also submitting them to the journal Herpetologica. The reports have since been submitted.

“The most striking aspect of the survey was that huge areas of suitable habitat were completely devoid of tortoises. A sure sign that the collectors had been in to collect them for either local consumption as food or collection for black market to supply the pet trade,” says Walker.

He estimates that two million wild northern spider tortoises remain.

“That sounds quite a lot. But 35% occur in a very small area of forest and are susceptible to being wiped out pretty quickly by collectors.”

“The remaining animals are in very isolated and fragmented populations with very low numbers of tortoises, which are unlikely to recover into healthy populations,” Walker says.

“As an educated and conservative guess I would say that the global population of northern tortoises have probably decreased by greater than 90% since human induced pressure has been placed on the animals.”

Some local communities hunt the tortoise for food. But the greatest threat comes from organised gangs visiting the area and collecting spider tortoises for illegal export. A single spider tortoise can reach US$1000 each on the pet and exotic reptile market, prices that drive the unsustainable trade. The northern subspecies is probably facing greater threats than the other two subspecies from poaching, by local populations as a food source and also by gangs for export to support the illegal pet trade in the animal.

Picture above shows tortoises poached on the southern side of Madagascar.

The other two subspecies don’t tend to end up as readily on the pet market and the tribes further south won’t eat them, however they are suffering from an alarming rate of habitat destruction, says Walker. He also says the threat to the tortoises from poaching is currently greater due to the current political turmoil in Madagascar brought about by the political coup in January.

Disorganisation at government level has meant that it is easier to get endangered species out of the country with false paperwork or blank permits that are easier to get hold of, he explains. Its quite clear to say that within the government of Madagascar there are some heavy and very keen most likely ruthless and dangerous wildlife syndicates or Don’s that are orchestrating the illegal wildlife trade within Madagascar while safe and practically untouchable within their “roles” as country leaders, advisers and ambassadors. To be honest the entire affairs stink and trade sanctions should be considered against the Madagascan government to preserve our species before anymore losses are seen.

Poachers camp located in Madagascar shows tools of the trade used to kill and protect the poachers from law enforcement agencies and for easy travelling among the dense forestland. Spider tortoises and young can be clearly seen in the back ground too.

Bush-meat trade;

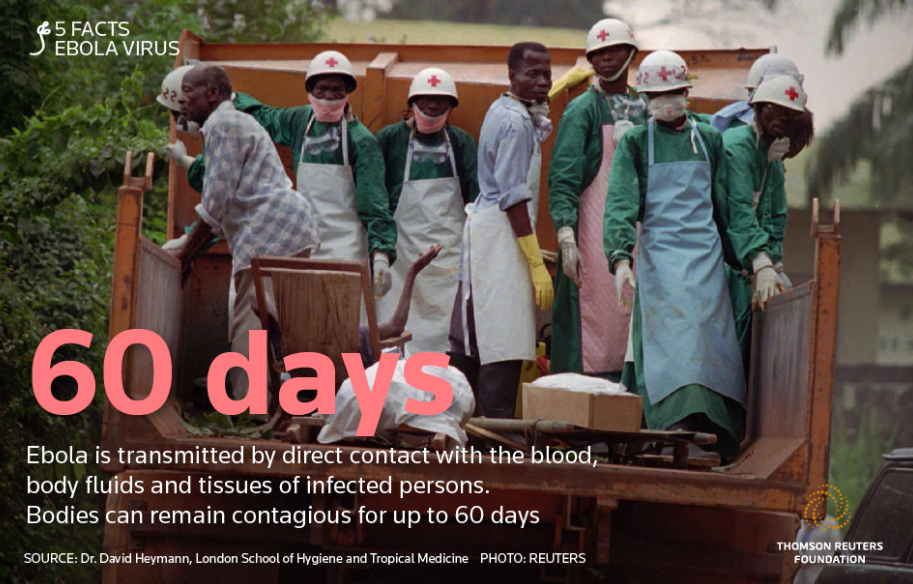

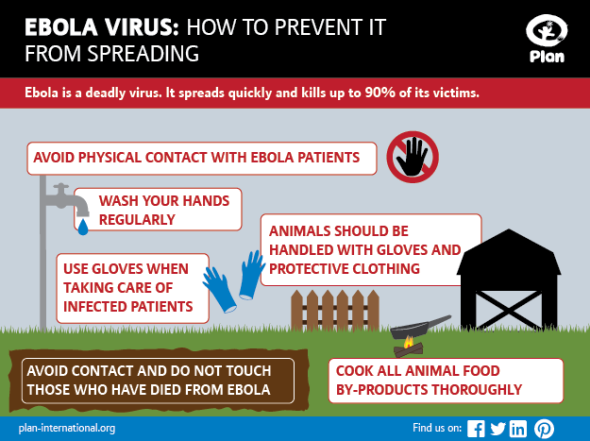

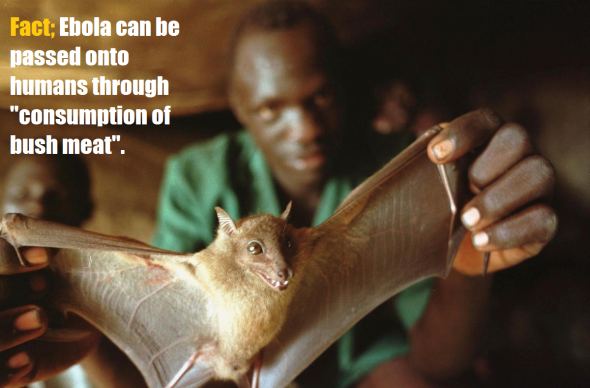

Patterns of bush-meat consumption has revealed extensive exploitation of protected species in eastern Madagascar and from looking at the facts present it doesn’t look set to end in the near future which is yet another factor placing our species of wildlife in Madagascar under immense threat. Even more concerning and on such a small island is the threat of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever. Currently as yet there are no confirmed cases however as we have explained and warned many times its only a matter of time that more virus are going to emerge within Africa and Asia. Fruit bats that are quite commonly killed and consumed all over Africa including Madagascar do pose a significantly high threat of spreading Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever to the locals. If such a virus did hit this island containing it would prove to be more of a headache than it currently is within Western Africa.

Using interviews with 1154 households in 12 communes in eastern Madagascar, as well as local monitoring data, conservationists investigated the importance of socio-economic variables, taste preference and traditional taboos on consumption of 50 wild and domestic species. The majority of meals contain no animal protein. However, respondents consume a wide range of wild species and 95% of respondents have eaten at least one protected species (and nearly 45% have eaten more than 10). The rural/urban divide and wealth are important predictors of bush-meat consumption, but the magnitude and direction of the effect varies between species. Bush-meat species are not preferred and are considered inferior to fish and domestic animals. Taboos have provided protection to some species, particularly the Endangered Indri, but evidence now shows that this taboo is rapidly eroding. The Indri is facing danger.

By considering a variety of potential influences on consumption in a single study conservation teams have improved understanding of who is eating bush-meat and why. Evidence that bush-meat species are not generally preferred meats suggest that projects which increase the availability of domestic meat and fish may have success at reducing demand. We also suggest that enforcement of existing wildlife and firearm laws should be a priority, particularly in areas undergoing rapid social change. The issue of hunting as an important threat to biodiversity in Madagascar is only now being fully recognised. Urgent action is required to ensure that heavily hunted species are adequately protected.

Boy carrying a recently killed Indri (the largest remaining lemur in Madagascar).

Recent analysis results shows a mixed diet of both protected species, and non-protected species consumed within the bush-meat trade on Madagascar. The results can be seen below;

The 1,154 households with which we carried out interviews were split 11.4% urban and 88.6% rural. The majority of people in our rural sample classify themselves as farmers (more than 70% in all wealth categories), while more than 60% of urban people in all wealth categories say their livelihood is based in salaried work. There were slightly higher numbers of migrants in the urban than the rural samples (36.2% and 27.4% respectively).

Of 3425 meals sampled in our dataset, the majority (74.5%) contained no animal protein, 11.8% contained protein from domestic animals and 13.7% contained protein from wild-caught animals. Of the 469 meals containing wild meat, the majority were fish and aquatic invertebrates, with only 9.6% from terrestrial wild animals (1.3% of all meals). The proportion of meals reported to contain meat from legally protected species (i.e., those categorised as strictly protected or protected) was very small (18 meals, or 0.5%).

There was strong support for the model which included all three predictor variables. Predictions generated from the fitted model show the influence of the modelled predictors on the consumption of animal protein in Malagasy households.

Urban households consume approximately twice as many meals containing meat as rural households on average (52.8% and 25.8% respectively), and migrants consume nearly twice as many meals containing meat than residents (41.9% and 29.4% respectively). Similarly, the proportion of meals containing meat is higher in households with a greater number of rooms, with households having three or more rooms consuming on average 60% more meals containing meat than single-room households (41.4% and 25.8% respectively). The size of the effect of each of the three variables was greater for domestic meat that for wild meat.

Within reports highlighted a few days ago by the IUCN and scholarships, conservationists “could” be correct in stating the bush-meat trade is not as bad as it has been portrayed. However while these researchers have questioned those consuming meat both domestic and wild it only relates to a small minority and not the millions of people that inhabit Madagascar.

Picture above depicts five prepared Lemur Sifaka’s.

Despite the low proportion of meals containing meat from wild-caught animals, and the small percentage of meals reported to include meat from legally protected species, many individuals report having eaten protected species at some point in their lives. From the raw data, 95% admit to having eaten a protected or strictly protected species, and 44.5% have eaten 10 or more protected or strictly protected species. 96 percent have eaten game species.

Should bush-meat trade continue at the rate it is of which see’s many species of lemur poached for wild food then extinctions could possibly occur sooner than expected. However while bush-meat trade, poaching, hunting, mining and timber trade pose major risks to the wildlife of Madagascar human over-population is quite likely going to see a mass change in biodiversity on the island. To what extent we do not fully know.

Other unsustainable practices threatening Madagascan wildlife;

Madagascar is among the world’s poorest countries. As such, people’s day-to-day survival is dependent upon natural resource use. Most Malagasy never have an option to become doctors, sports stars, factory workers, or secretaries; they must live off the land that surrounds them, making use of whatever resources they can find. Their poverty costs the country and the world through the loss of the island’s endemic biodiversity.

Recap;

Madagascar’s major environmental problems include, deforestation and habitat destruction, agricultural fires, erosion and soil degradation, overexploitation of living resources including hunting and over-collection of species from the wild, Introduction of alien species.

Erosion;

With its rivers running blood red and staining the surrounding Indian Ocean, astronauts have remarked that it looks like Madagascar is bleeding to death. This insightful observation highlights one of Madagascar’s greatest environmental problems—soil erosion. Deforestation of Madagascar’s central highlands, plus weathering from natural geologic and soil conditions, has resulted in widespread soil erosion, which in some areas may top 400 tons/ha per year. For Madagascar, a country that relies on agricultural production for the foundation of its economy, the loss of this soil is especially costly.

Picture above depicts just how bad soil erosion is within Madagascar. The photo may seem quite a pretty site however its environmental carnage for aquatic species that cannot see, breath or even hunt adequately. Soils on the island are being brushed up by the winds then lain into the local and big rivers. This leads to sludge and other deposits contaminating the rest of the land effecting both land and aquatic wildlife.

Overexploitation of living resources;

Madagascar’s native species have been aggressively hunted and collected by people desperately seeking to provide for their families. While it has been illegal to kill or keep lemurs as pets since 1964, lemurs are hunted today in areas where they are not protected by local taboos (fady). Tenrecs and carnivores are also widely hunted as a source of protein. Reptiles and amphibians are enthusiastically collected for the international pet trade. Chameleons, geckos, snakes, and tortoises are the most targeted.

The waters around Madagascar serve as a rich fishery and are an important source of income for villagers. Unfortunately, fishing is poorly regulated. Foreign fishing boats encroach on artisanal fishing areas to the detriment of locals and the marine fauna. Sharks, sea cucumbers, and lobster may be harvested at increasingly unsustainable rates.

Introduction of alien species;

The introduction of alien species has doomed many of Madagascar’s endemic species. The best example of damage wrought by introduced species can be found in the island’s rivers and lakes. Adaptable and aggressive tilapia, introduced as a food fish, have displaced the native cichlids.

Picture depicts cichlids that are one of Madagascar local endemic species now under threat from alien species not native to the island. The introduction of alien species seems to be quite a large problem on the continent of Africa too. South Africa is one prime example where some 39 species of flora and under threat from alien species.

There is really little use bemoaning past environmental degradation in Madagascar. Now the concern should be how to slow this ecological decline and how to best utilize lands already degraded so they support productive activities today and for future generations. Without improving the well-being of the average Malagasy, we cannot expect Madagascar’s wildlands to persist as fully functional systems and continue to cater to the needs of their people and that is sadly the main problem we have within Madagascar and much if not all of Africa. When we see people attack Africans for eating bush meat, pet meat, or poaching its sometimes hard to explain why these individuals are behaving the way they do. Civil tensions and war has really not helped too.

In part two I will include a more detailed look of over-population and how it “could” eventually lead to the islands tipping point of wildlife.

Conclusion;

Madagascar is one of the planets most impoverished islands off the African continent. Human over-population has played a catastrophic role in depleting vast areas of land, reducing many species of native flora and fauna and has created many problems that conservationists around the world are fighting in vain to end. There is no quick fix to Madagascar and it is saddening to know that even with the most professional conservation efforts underway as I type we will most certainly see 70-80% of species pushed into extinction on the island of Madagascar. Areas of forestry and land that lay bare must be worked on, immigration must be tightened, corruption at government level must be removed, ecotourism MUST be increased that will increase employment, decrease wildlife degradation, and habitat fragmentation. Conservation efforts must increase in all areas where wildlife is deemed “threatened” and species of wildlife that are verging borderline extinction must be trans-located into safer areas and secured to secure their future. Madagascar is not a wealthy island so while many lands lay bare introducing new tourism hot spots would be beneficial for the people of Madagascar and her wildlife. Failing all of this we will unfortunately be witnessing mass extinctions occurring in under twenty years. It must also be noted that nearly 11 million people in Madagascar have no access to clean and safe water. The effects are huge both to humans that are ripping the land to pieces in search of water and to wildlife suffering because of it.

We MUST help and do more… Before its to late. To find out more on how you can help the people of Madagascar suffering form poverty please click >here<

You can also donate to International Animal Rescue Foundation F.A.W.S project here that helps to reduce poaching, equips anti poaching teams in need, reduces bush meat and pet meat trade and helps secure the lives of many orphaned mammals all over the continent of Africa. Please donate >here< or alternatively if your using Facebook and wish to use our secure and safe application to donate you can donate >hereto<

Thank you for reading

Dr Josa C. Depre

Conservationist and Botanical Scientist

Malagasy government and environmental non-profits must do more to stem the flow of wildlife loss before its to late.

Notice a typing error? contact us today and we’ll fix it as soon as possible. Contact International Animal Rescue Foundation here