Endangered Species Friday: Amazona versicolor

Endangered Species Friday: Amazona versicolor

This Fridays Endangered Species Post (ESP) I touch up briefly on the St Lucia Amazon as the species is commonly known. Image credits Philippe Feldman

The species was identified back in 1776 by Dr Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller (April 25, 1725 – January 5, 1776) who was a German zoologist. Dr Statius Müller was born in Esens, and was a professor of natural science at Erlangen. Between 1773 and 1776, he published a German translation of Linnaeus’s Natursystem.

The supplement in 1776 contained the first scientific classification for a number of species, including the dugong, guanaco, potto, tricolored heron, umbrella cockatoo, red-vented cockatoo, and the enigmatic hoatzin.

Dr Muller was also an entomologist. Müller died in Erlangen. He is not to be confused with Salomon Müller (1804–1864), also an ornithologist, or with Otto Friedrich Müller. Note that the family name is actually spelled without the umlaut, then and now.

The Saint Lucia Amazon is listed as (vulnerable) which was nearing (endangered), native to Saint Lucia. From 1988 the species was first listed as (near threatened), however, unfortunately from 1994-2016 the species was re-listed as (vulnerable). Locals commonly refer to the species as the; Saint Lucia Amazon, or the Saint Lucia Parrot.

Populations are considered to be extremely low, although now allegedly increasing. A decade ago the then current known population rate stood at some 350-500 individuals, this generally equates to some 230-330 ‘mature individuals’. This number was actually considered quite low for any species which technically should see the St Lucia listed as (critically endangered).

St Lucia Amazon Parrot is situated on the island of St Lucia in the eastern Caribbean where it is known locally as ‘Jacquot’. The Government of the island became aware of the plight of its endemic parrot population in 1975 when Durrell first became involved with St Lucia, and the Trust was asked to help by starting a captive breeding programme for the species at its Jersey headquarters. In 1989 a pair of captive-bred parrots returned to their native home with the Prime Minister of St Lucia.

The St Lucia Amazon’s natural habitat is subtropical or tropical moist montane forest, diet consists of fruit and insects, of which clutch size is around 3-4 eggs. The species is threatened by habitat loss. St Lucia Amazon species have declined from around 1000 birds in the 1950s to 150 birds in the late 1970s. At that point a conservation program began to save the species, which galvanized popular support to save the species, and by 1990 the species had increased to 350 birds.

Although the population in Saint Lucia is small it is still expanding. To date after conservation efforts increased on the island of St Lucia due to destructive storms and hurricanes populations were increased to some 2,100 mature individuals. Please see video below.

The story of this birds salvation from the brink of extinction (including the influence of conservationist Paul Butler) is told in Chapter 7 of the 2010 book “Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard” by Chip & Dan Heath.

Listed on Cites Appendix I and II, below I’ve included a list of identified threats associated with the St Lucia Amazon Parrot.

MAJOR THREATS

The human population of St Lucia is growing at a considerable rate, increasing pressure on the forest and resulting in habitat loss. Selective logging of mature trees may significantly reduce breeding sites, and hurricanes, hunting and trade pose further threats. There have been recent efforts to lift the moratorium on hunting within forest reserves, which would seriously threaten this species.

Image: St Lucia Amazon

Its truly wonderful to know that conservation efforts have brought this species back from the brink of near extinction. The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust is one trust that I admire, and have donated many hundreds of euros to since I was a teenager. Durrell have worked wonders across the globe working to help primates, frogs and countless birds, not forgetting many other animals..

The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust is one NGO that I myself will be leaving money to in my will. Why? Because they deserve the money for the work they put into preserving our flora and fauna. You can donate to the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust here: https://www.durrell.org/wildlife/shop/donation/

Thank you for reading and have a nice day.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Chief Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/InternationalAnimalRescueFoundationAfrica/?fref=ts

Endangered Species Monday: Papilio homerus |Extinction Imminent.

Endangered Species Monday: Papilio homerus

This Mondays (Endangered Species Post) E.S.P, I document again on this stunning species of swallowtail butterfly. I last documented on this amazing species of butterfly two years back, unfortunately conservation actions that were ongoing back then still don’t seem to really be improving the current status of the largest swallow tail butterfly in the Western Hemisphere. Image credited to Dr Matthew S. Lehnert.

Despite the species nearing (complete extinction) within the wild, with a possible extinction likely to occur soon, biologists and conservationists are doing all they can to improve the current status of this beautiful insect, we can only hope for the best, or that the Jamaican Government increases further protection for the species, thus earmarking funding for conservation teams on the ground to preserve our largest Western Hemisphere species of swallowtail.

Endemic to Jamaica, the species was first discovered by Professor Johan Christian Fabricius (7 January 1745 – 3 March 1808) who was a Danish zoologist, specializing in “Insecta”, which at that time included all arthropods: insects, arachnids, crustaceans and others. He was a student of Professor Carl von Linnaeus, and is considered one of the most important entomologists of the 18th century, having named nearly 10,000 species of animals, and established the basis for the modern insect classification.

Professor Johan Christian Fabricius first identified and documented on P. homerus back in 1793. The common name for this swallowtail butterfly is known as the Homerus Swallowtail, which is listed as [endangered]. Back in 1983 the species was first listed as [vulnerable]. Then from 1985-1994 the species was re-listed as [endangered]. Evidence shows from 2007 we almost lost the species, of which conservation press and media pleaded with the public for help, which did in a way increase awareness. Sadly we need more awareness on and about this butterfly.

The specie hosts a wingspan of some fifteen centimeters, the Jamaican swallowtail is said to be the second largest swallowtail of its kind on the planet, with the African swallowtail alleged to be the largest. The species can only be located within the forests of Jamaica, of which habitat loss remains the largest yet significant threat associated with this species of swallowtail butterfly, butterfly collecting is alleged to be the second largest threat. Parasitic wasps also pose a large threat to the P. homerus too.

Back in the 1930’s P. homerus was considered to be somewhat common throughout Jamaica, however, regrettably the species can now only be located within the Blue and John Crow Mountains in eastern Jamaica. Population count is [estimated to be no fewer than fifty individuals], which theoretically makes this super stunning butterfly one of the planets most threatened species of insects.

P. homerus is included on the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species wild flora and fauna (Cites), of which (all domestic and international trade of this species is strictly illegal). Collection for display and trade is illegal, and finally destruction of the swallowtail butterflies habitat is furthermore strictly ‘forbidden’.

It has been suggested that the species could/may ‘benefit from captive breeding’, more data on this subject can be located hereto http://www.troplep.org/TLR/1-2/pdf005.pdf The caterpillars feed exclusively on Hernandia jamaicensis and H. catalpifolia; both of which also are endemic to Jamaica.

The Giant is a peaceful lover of a quiet habitat and is normally found in areas that remain undisturbed and unsettled for the most part, although due to destruction of its habitat can rarely be found at some cultivated edges of the forests on the island. P. homerus primary and favorite residence is usually the wet limestone and lower montane rain forests, however, it is now isolated to only 2 known locations on the island of Jamaica. The reproduction habits are not well known but like most of its fluttering cousins, it feeds on leaves and flowers where it also breeds and lays eggs that develop on the host plants.

P. homerus future remains critical, and its quite likely that we’re going to see yet another extinction occur sometime very soon. As much as I hate to say this, I do honesty believe that a complete wild extinction may occur in no fewer than 1-2 years (if that). However I believe based on the current populations, data, and habitat destruction, that extinction will occur sooner than that. I am not aware (as explained) of any captive breeding programmes, which if such projects are not undertaken now, we’ll see the species gone for good in under a year.

Image: P. homerus caterpillar.

Thank you for reading, and please share this article to create more awareness relating to the Jamaican swallowtail, and lets hold our breath and pray to almighty God that somewhere out there, wherever God may be, a miracle may occur.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Follow our main Facebook page here: https://www.facebook.com/InternationalAnimalRescueFoundationAfrica/

International Animal Rescue Foundation and Environmental News & Media are looking for keen, enthusiastic, environmental and animal lovers to write alongside us. We do not pick sides, and show both sides to every-story. We like to take a more middle stance, rather than a one-sided stance. If you would like to spare an hour of your time, per week, voluntarily writing for us, or your own environmental/animal welfare related issue please contact us via the contact box below.

Please note that we have since moved our main communications website to a new and more professional server that will be hosting everything from real life news, real time projects, world stories, environmental and animal rescues and much more. International Animal Rescue Foundation is a 100% self funded environmental company. While we don’t rely on donations, you can make a donation to us via our main Anti Pet & Bush Meat Coalition organisation page.

Have a nice day.

Endangered Species Friday: Dendrolagus dorianus | Cuddly Teddy Bear Facing Extinction.

Endangered Species Friday: Dendrolagus dorianus

This Friday’s (Endangered Species Post) [E.S.P] I touch up on this rather unusual species of tree kangaroo that’s rarely mentioned within the world of conservationism. Furthermore I also wish to set the record straight about these wonderful and utterly adorable species of mammals which many people seem to believe are endemic ‘just to Australia’. This particular species is actually native to Papua New Guinea, generically identified as Dendrolagus dorianus. (Image credits: Daniel Heuclin).

Listed as (vulnerable), the species was primarily identified by Dr Edward Pierson Ramsay (3 December 1842 – 16 December 1916). Dr Ramsay was an Australian zoologist who specialized in ornithology. Among organisms Dr Ramsay named are the pig-nosed turtle, giant bandicoot, grey-headed robin and Papuan king parrot.

D. dorianus lives within a country of immense cultural and biological diversity. A country known for its beaches, coral reefs and scuba diving. Not forgetting the countries inland active volcanoes. Locals commonly identify the animal as the; Doria’s tree kangaroo or the unicolored tree kangaroo. Doria’s tree kangaroo is within the order of Diprotodontia, and the family identified as Macropodidae.

Since 1982 to 1994 the species has remained at [vulnerable level] of which back in 1996 a further assessment of the species noted a possible population decline. The decline prompted environmentalists to notch the species further up the list of [vulnerable species]. However a survey in 2008 concluded the species hadn’t as yet qualified for any further threatened status (E.g) endangered (which would unfortunately be the next listing should threats not decline in the wild).

Scientific research and population evaluations have shown a staggering 30% decline of overall wild populations which is quite a large population decrease, although “allegedly not concerning enough as yet to reclassify this particular specimen as endangered”. Yes its unfortunate that the current news relating to (decreasing populations), is indeed factual, and its likely (as explained), that should threats in the wild not decrease anytime soon, we could see a new extinction occurring in as little as ten years “if not sooner”. Populations are not known to be ‘fragmented’.

Image: Rare glimpse of the Doria Tree Kangaroo.

Identified in 1883 there are very few conservation actions actually known that could help increase declining population sizes which I myself find somewhat frustrating, not to mention perplexing, especially when one takes into consideration the current level of threats associated with this specie in Papua New Guinea.

Research proves the species inhabits some several protected national parks [NP’s], unfortunately extreme hunting activities I.e illegal poaching is still ongoing. While Anti Poaching Operations [APU’s] do exist, the fact of the matter is that Cites (The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species Wild Flora and Fauna), still hasn’t listed the species as (protected or endangered) on either Appendix I or Appendix II.

Image: Extinction may occur in a decade of not sooner.

To date the current population level is unknown, furthermore reproduction is also believed to be incredibly low and poor.

MAJOR THREATS

Known threats relate to the bush meat trade, which if not controlled will unfortunately push the species into extinction. Hunting with dogs, unregulated/illegal hunting is quite high and problematic within the region. Finally the species absolutely hates canines of which when threatened emits depressed vocalizations. Future threats have been identified as habitat loss and degradation.

The Doria’s tree kangaroo lives at elevations of some 600-3,650 meters of which is mostly nocturnal and a solitary animal. Dr Ramsay named the species after Professor Marquis Giacomo Doria (1 November 1840 – 19 September 1913) whom was an Italian naturalist, botanist, herpetologist, and politician of Italy.

Doria’s tree kangaroo is probably one of the largest species of tree kangaroos on the planet, although this is somewhat debatable. Weighing in at 6.5-14.5 kilograms, length is around 60-80 centimeters, with a tail length of some 40-70 centimeters. With a large tail, dense black and brown fur, large powerful claws and stocky build, the appearance of this specific animal almost appears to look like a medium sized bear.

Diet consists of leaves, flowers, fruits and buds, there is no evidence that suggests or points to any form of meat eating either. Gestation period of females is around thirty days, of which the ‘single young baby’ will remain in mothers pouch for around ten months.

There really is limited information about this specific species which could be due to the fact the species is actually very rare, nocturnal, and lives at moderate to high elevations within dense montane forests. I am asking the public to please share this article far and wide to help us push more awareness of this species into the public domain, which we hope will encourage (Cites) to protect the species sooner rather than later.

This article is dedicated to Ms Toni Devine, a wonderful young lady that absolutely adores these wonderful species of animals, who wouldn’t adore them, they are truly remarkable, intelligent, and in way more like cuddly teddy bears.

Chief Environmental & Botanical Officer

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental Crimes Investigator

Follow me on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/josedepre11

Follow us on Facebook via clicking the link below:

https://www.facebook.com/InternationalAnimalRescueFoundationAfrica/

Endangered Species Monday: Tremarctos ornatus

Endangered Species Monday: Tremarctos ornatus

This January’s (2016) Endangered Species Watch Post is dedicated to the Tremarctos ornatus, commonly known as the Andean Bear or Spectacled Bear. The species was identified by Dr Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier back in 1825. Dr Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier lived from (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the “Father of paleontology”. Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century and was instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in comparing living animals with fossils.

From 1982 to 1996 the Andean Bear has been listed as (vulnerable), of which its main threats are habitat loss and major poaching for the animal parts trade. Within the past thirty years populations have declined by a staggering 30% which qualifies the bear as being listed as (vulnerable). Habitat loss continues at a rate of 2-4% per year, which as yet doesn’t look set to decline. Furthermore identified threats do not look set to decrease anytime soon which could see this stunning animal pushed into extinction very soon.

Poaching is one of the main problems that can be controlled if (anti poaching enforcement) is increased within the bears habitat, unfortunately this is easier said than done. Furthermore, continued habitat destruction and illegal logging will see forest tracks opened up within the bears natural habitat, thus allowing poachers to walk freely into the bears home environment, thus seeing poaching occur. Anti poaching enforcement is a must, and needs to be taken seriously by all international (non-governmental organisations) that are working to sustain this animals welfare, and habitat.

Endemic to Bolivia, Colombia; Ecuador; Peru, and Venezuela, populations of the Andean Bear are now known to be decreasing rapidly, however populations are not reported to be (fragmented). Back in 1998 it was estimated by Dr Peyton that there was a mere 20,000 Andean Bears remaining. A 2003 survey, however estimated that there was in between 5,000 to 30,000 Andean Bears remaining. Andean Bears are now commonly located within the eastern Andes of which bear populations exist from the snowline down to 300 m asl in the Tapo-Caparo National Park in Venezuela. Andean Bears can also be located at high altitudes in Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Columbia.

Andean Bears are “omnivores”, meaning that they feed exclusively on plant matter, fruits, bark and occasionally will consume meat of other animals, the bears preferred diet though is reported to be species of flora from the Bromeliaceae and Arecaceae. Activity patterns range from strictly diurnal for wild bears in Bolivia to mixed diurnal and nocturnal for reintroduced bears in Ecuador.

“EXTINCTION BY 2030 IS POSSIBLE”

As food is available year-round in all parts of their range, Andean bears do not hibernate. Based on the first few individuals of this species to be monitored using ground telemetry in Bolivia and Ecuador, home ranges overlap to a high degree and minimum home range sizes vary from 10 to 160 km² (although these are underestimates, as the bears were regularly out of range of radiotelemetry in both studies).

The Andean Bear stands at around 5ft to 6ft tall, and weighs in at around 220, 330lbs. The markings on the Andean bear’s face, neck and chest are exactly like human finger prints (unique to each and every individual Andean Bear). Andean bears are very timid and shy and prefer to live in isolated cloud forests, of which they are “mainly nocturnal” however will at times feed, live and socialize in daylight (although this is considered rare). Favorite foods are cacti, berries and of course honey.

Andean bears are quite typically solitary animals, and will only be seen in pairs during mating season. Females normally give birth to (1-2 cubs), cubs are normally mobile after one month, however will remain with their “mother” for up to eight months, mothers will often be seen with little cub hitching a ride on the back on the mothers back. Population studies state today that there may be no fewer than 3,000 Andean bears in the wild., which if true could soon see the species nearing extinction by 2030.

ANDEAN BEAR THREATS

Habitat loss and fragmentation, poaching, and the lack of knowledge about the distribution and status of the Andean Bear are the principal threats to this species. Much of the range of the Andean Bear has been fragmented by human activities, largely resulting from the expansion of the agricultural frontier. In some areas, mining, road development and oil exploitation are becoming a greater menace to Andean Bear populations as well as to local communities, due to land expropriation, loss of habitat connectivity, and water and soil contamination.

Many Andean Bear populations are isolated in small to medium-sized patches of intact habitat, particularly in the northern part of the range. The situation tends to improve towards the southern range, with some large patches of wilderness still remaining. Nevertheless, human population growth and national development plans throughout the Tropical Andes continue to be an important cause of habitat fragmentation and to threaten the connectivity among remaining wilderness patches.

Poaching is a serious threat throughout the Andean Bear range. Bears are often killed after damaging crops, particularly maize, or after purportedly killing livestock. Also, Andean Bear products are used for medicinal or ritual purposes and at some localities Andean Bear meat is highly prized. Live bears are also sometimes captured and sold.

Human induced mortality endangers the viability of small remnant populations. Lack of knowledge about the distribution and status is a problem throughout the region. In many areas, information about the status of Andean bears is outdated or, particularly in the southern portion of the range, simply non-existent. The absence of knowledge makes it difficult to develop realistic management plans for the conservation of this species, or to monitor changes in its distribution (reflective of changes in population status).

It is without a doubt the Andean Bear is facing “imminent extinction”, and from studies that are being conducted by various organisations including the International Animal Rescue Foundation Brazil, its very likely this animal is going to be pushed into extinction very soon.

Thank you for reasding the first part of this years (2016) Endangered Species Watch Post, and please feel free to scroll through 2014-2015’s posts below via the automatic scroll new feed bar.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M. Environmental & Human Science

Chief Environmental Officer and Director

Donate today and help us continue our worldwide anti-wildlife trade enforcement operation continuing. Please click the DONATE button below.

DONATE BUTTON

Endangered species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

Endangered Species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

This Fridays endangered species I speak up about the now (not co common Cheetah). Endangered Species Watch Post (ESP) tries to limit the amount of commonly known specie on the platform, however due to recent declines we’ve now included the specie within the (ESP).

Listed on the ‘threatened list’ of (endangered species) as vulnerable, the common Cheetah was formally identified by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (1739 in Weißensee, Thuringia – 1810 in Erlangen), often styled I.C.D. von Schreber, was a German naturalist. (Image Cheetah, photographer unknown).

Identified back in 1775 there remains a total of some five sub-species known that inhabits north, south, west and east Africa. The sub-species A. j. venaticus is known only to inhabit Iran. Some very contradictory reports state there may or may not be populations living within Central India too.

From 1996 to 2002 A. jubatus populations haven’t increased of which this amazing hunting cat commonly known as the Cheetah or (Hunting Leopard) continues to sit at (vulnerable listing). Further population declines will most certainly see the specie qualifying for the category of (endangered). Should this occur the African Cheetah will become the first specie of big cat within the new millennium to hit endangered level.

Cheetahs have disappeared from some seventy six percent of their known historical range which now overtakes that of the Panthera leo (Lion). African populations are considered ‘widely common’ however still known to be sparsely populated. Meanwhile in Asia the Cheetah has practically vanished which is why we must do more to protect the last known remaining Africans populations before further extinctions occur. Cheetahs were known to be quite common throughout Mediterranean and the Arabian peninsula, north to the northern shores of the Caspian and Aral Seas, and west through Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan into central India However this is no longer the case.

One reason for for Asiatic Cheetah population declines was due to live captures of the animal which were trained to hunt other fauna. Unfortunately that was not the main reason why the specie spiralled into near extinction. The primary threat was Cheetah prey decline. This same problem has also been noted as effecting other big cats within Africa and Asia too. Agriculture, over-unregulated-hunting, over-culling, urbanization and habitat destruction via humans, has all played a significant role pushing the species furthermore into the realms of near extinction. Within Iran the sub-species A. j. venaticus is known to be (critically endangered)

In Tunisia Cheetahs were known to roam freely, however there are no known populations remaining within the country. The El-Borma region, near the Algerian boundaries, was probably among the areas where Cheetahs have last been seen in 1974 and documented. Reports compiled back in 1980 now tell us the specie is incredibly rare (if not regionally extinct already). Recently hunters yet again stated that (hunting) has never impacted on the species whatsoever. That’s a complete barefaced lie by members of (PHASA) Professional Hunting Association of South Africa and (DSI) Dallas Safari International.

Cheetahs became extinct from most of the Mediterranean coastal region and easily accessible inland habitats of El-Maghra and Siwa oases one decade after being widely distributed in the northern Egyptian Western Desert until the 1970s. The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands). Please view images lower down the article.

“The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands)”…

Current data on Cheetah population within Eritrea, Sudan and Somali is unknown. Populations within these three countries could very well already be extinct. Reports conducted within most “known Chad Cheetah zones” have sadly concluded the species is no longer present within the of much African country either, 2008 surveys did pick up few roaming species within Southern Chad though. Few populations remain within Central Sahara although to what extent is again unknown.

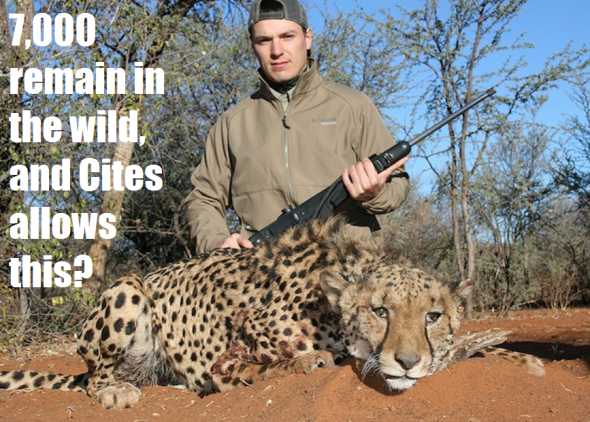

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Within the African countries of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, and Democratic Republic of Congo again population counts are not known. (Its’ quite possible that the species has already gone extinct). Cheetahs are already officially extinct within Burundi and Rwanda. Reports have sadly confirmed the species is also extinct within Nigeria. Poaching and over-hunting have wiped all populations out within the three central African countries. A 1974 study ‘suggested’ that few populations may be occupying both Cameroonian boundaries and Yankari Game Reserve. This report is though mere speculation and not confirmed evidence.

EXTINCTIONS TO DATE

Regional Extinctions

Extinctions have already occurred within; Burundi; Côte d’Ivoire; Eritrea; Gambia; Ghana; Guinea; Guinea-Bissau; India; Iraq; Israel; Jordan; Kazakhstan; Kuwait; Oman; Qatar; Rwanda; Saudi Arabia; Sierra Leone; Syrian Arab Republic; Tajikistan; Tunisia; Turkmenistan; United Arab Emirates; Uzbekistan and Yemen.

Possible Extinctions

Afghanistan; Cameroon; Djibouti; Egypt; Libya; Malawi; Mali; Mauritania; Morocco; Nigeria; Pakistan; Senegal, Uganda and the Western Sahara.

Known Endemic Zones

Algeria; Angola; Benin; Botswana; Burkina Faso; Central African Republic; Chad; Congo; Ethiopia; Iran; Kenya; Mozambique; Namibia; Niger; South Africa; South Sudan; Sudan; Tanzania, United Republic of; Togo; Zambia; Zimbabwe. (Updated 2015)

2015 WILD POPULATION COUNTS

(Please note the following populations below are wild and not captive nor farmed)

Reintroductions of Cheetah populations have taken place within Swaziland however to what extent the populations are within Swaziland is unknown.

What we know to-date is that populations within the “Southern Africa” (not just South Africa) hosts the largest populations at roughly some 5,000+ mature individuals. Botswana and Malawi holds roughly 1,800 mature individuals. Populations are unknown within (Angola) and ‘considered possibly extinct’. Mozambique holds some 50-60 mature individuals, Namibia 2,000. SOUTH AFRICA holds some 550 mature individuals, Zambia some 100 mature individuals, Zimbabwe 400. A large proportion of the estimated population lives outside protected areas, in lands ranched primarily for livestock but also for wild game, and where lions and hyenas have been extirpated. So we do question why trophy hunting and unregulated hunting still persists out of farmed areas.

Ethiopia, southern Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania holds an estimated (2,500 mature individuals) however due to intense hunting pressure, poaching and habitat destruction this number could be much lower. (There is NO evidence that hunting within any of the ‘legal zones’ has increased Cheetah populations whatsoever”. Furthermore I challenge all hunting organisations within the legally allowed hunting areas to prove myself wrong? The largest population (Serengeti/Maro/Tsavo in Kenya and Tanzania) is estimated at 710.

Kenya hosts some 790+ mature wild individuals, Tanzania 560+ to 1,100 individuals. Uganda, Gros and Rejmanek (1999) estimated 40-295 with a wider range in the Karamoja region, whereas now Cheetahs have been extirpated and just 12 are estimated to persist in Kidepo National Park and surroundings. North-West Africa the species stands at no fewer that 250 mature individuals (if that).

Within Iran the ‘sub-species’ of Asiatic Cheetah - A. j. venaticus (if still extanct) stands at some 60-100 mature individuals. We do like the fact the conservation trustee is a known hunter allegedly supporting Cheetah conservation. We’ve yet to see an real improvement of Iranian Cheetahs in the country (more money talk)…

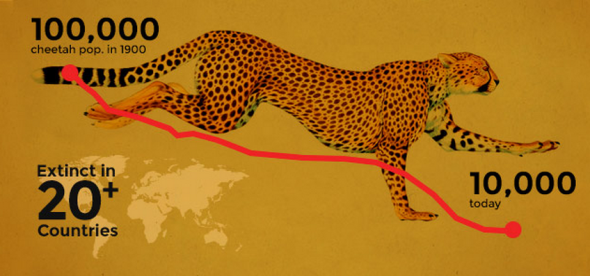

The overall “known Cheetah population” for Asia and Africa is by far more threatened that the Lion. To date there are some 7,000 known mature individuals remaining within the wild but no greater than 10,000. This sadly make the Cheetah by far more threatened than Panthera leo. African Lion populations stand at some 15,000 to 13,000 maximum. As the Cheetah population will not likely exceed 10,000 individuals - the species therefore qualifies for (vulnerable status).

Nowell and Jackson stated that Cheetah populations in the past have undergone some alarming declines, now it would seem that history is re-repeating itself (this time the specie may not survive). The Cheetah exhibits remarkable levels of genetic diversity in comparison and compared to other wild felids, so there could be a high chance the species may make it back from the near brink of extinction within the wild.

Problem is poaching and over-hunting then wasn’t as prolific as it is today. Scientists stated that interbreeding among other individuals had saved the species from bottleneck declines in the past. This history dated back some 10,000 years. Sport hunting then wasn’t an issue as it is today, so in all fairness the species could be hunted into extinction illegally or legally (with much thanks to Cites on the ‘legal part’). So in all honesty we may lose the Cheetah before the Lion.

While the causes of the Cheetah’s low levels of genetic variation are unclear [back then], what is clear is that large populations are necessary to conserve it. Since Cheetahs are a low density species, conservation areas need to be quite large, larger than most protected areas. Major areas of the African continent are being overtaken by humans, agriculture to cope with human expansion and deforestation. No longer is it a case of ‘if’ rather than ‘when’….

MAJOR THREATS

Cheetahs are ‘hunted for sport and trophies’, as well as handicrafts products. Live animals are also traded - the global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining. Pest animals are also removed.

In Eastern Africa, habitat loss and fragmentation was identified as the primary threat during a conservation strategy workshop (2007). Because Cheetahs occur at low densities, conservation of viable populations requires large scale land management planning; most existing protected areas are not large enough to ensure the long term survival of Cheetahs. A depleted wild ungulate prey base is of serious concern in northern Africa. Cheetahs which turn to livestock are killed as pests. Conflict with farmers and depletion of the wild prey base are also considered significant threats in parts of Eastern Africa.

In Iran, the Asiatic Cheetah A. j. venaticus is threatened indirectly by loss of prey base through human hunting activities. In addition, most protected areas are open to seasonal livestock grazing, which potentially places huge pressure on the resident ungulate populations through disturbance and potential competition. Additionally, domestic dogs accompanying the herds present a likely threat to both Cheetahs and their prey. An emerging threat is the possibility of fragmentation into discontinuous subpopulations as a result of increasing developmental pressures (mining, oil, roads, railways); this is particularly the case in Kavir N.P., currently the north-western limit of the Asiatic Cheetah’s range.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Conflict with farmers and ranchers is the major threat to Cheetahs in southern Africa. Cheetah are often killed or persecuted because they are a perceived threat to livestock, despite the fact that they cause relatively little damage. In Namibia, very large numbers of Cheetahs have been live-trapped and removed by ranchers seeking to protect their livestock (from government permit records, Nowell [1996] calculated that over 9,500 cheetahs were removed from 1978-1995). While removal rates have fallen, in part due to intensified conservation and education efforts, many ranchers still view Cheetahs as a problem animal, despite research showing that Cheetahs were only responsible for [3% of livestock losses] to predators. Although Cheetah in Iran have been killed because of predation on livestock, since 2003, there has been no direct evidence of killing Cheetahs, though it is likely most incidents go unreported.

“Cheetahs are also vulnerable to being caught in snares set for other species”.

Another threat to the Cheetah is interspecific competition with other large predators, especially lions. On the open, short-grass plains of the Serengeti, juvenile mortality can be as high as 95%, largely due to predation by Lions. However, mortality rates are lower in more closed habitats.

CITES [allows legal trade in live animals and hunting trophies under an Appendix I] quota system (annual quotas: Namibia - 150; Zimbabwe - 50; Botswana - 5). This was accepted by CITES as a way to enhance the economic value of Cheetahs on private lands and provide an economic incentive for their conservation. The global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining; Cheetahs [breed poorly in captivity] and in 2001 [30% of the captive population] was wild-caught. While analysis of trade records in the CITES database shows that these countries have reported almost no live exports since the late 1990s, Conservation groups are concerned that there is a substantial illegal cross-border trade in live animals.

There is also concern about illegal trade in skins, as well as capture of live cubs for trade to the Middle East. There is an increasing trade in cubs from [north-east Africa into the Middle East], but there is currently little trade in cubs from the Sahel region, where it was previously considered a major problem. Cheetahs are active during the daytime and there is concern that they can be driven off their kills by [tourist cars crowding around, or mothers separated from their cubs]. Burney (1980) conducted a study and concluded that [tourist cars did not seem to harm cheetahs, and in fact sometimes helped, as cheetah chases more often ended in a kill when there were cars around, distracting prey, providing cover from which to stalk, or otherwise waking Cheetahs up to notice prey in the area]. However, [tourist numbers have risen sharply by then, and its potential impact on cheetahs remains a concern].

The Eastern African Cheetah conservation strategy identified four sets of constraints to mitigating these threats across a large spatial scale. Political constraints include lack of land use planning, insecurity and political instability in some ecologically important areas, and lack of political will to foster Cheetah conservation. Economic constraints include lack of financial resources to support conservation, and lack of incentives for local people to conserve wildlife. Social constraints include negative conceptions of Cheetahs, lack of capacity to achieve conservation, lack of environmental awareness, rising human populations, and social changes leading to subdivision of land and subsequent habitat fragmentation. These potentially mutable human constraints contrast with several biological constraints which are characteristic of Cheetahs and cannot be changed, including wide-ranging behaviour, negative interactions with other large carnivores, and potential susceptibility to disease.

Disease is a potential threat to the Cheetah, as its reduced genetic diversity can increase a population’s susceptibility. However, the most serious disease mortality thus far documented in wild Cheetahs was from naturally occurring anthrax in Namibia’s Etosha National Park; Cheetahs, unlike other predators, do not scavenge carcasses of ungulates killed by anthrax, and thus [had no built-up immunity] when they preyed upon springbok sick with the disease. The Cheetah’s low density may offer some measure of protection against infectious disease; for example, Cheetahs were not affected by an outbreak of Canine Distemper Virus in the Serengeti National Park which [killed over 1/3 of the Lion population]. Serological surveys of Cheetahs on Namibian farmland indicate some exposure and survival of the disease.

We are losing the Cheetah faster than the specie of Lion. Although some regulations are in place with the species listed on Appendix I (Cites) its quite likely we’ll lose wild populations should hunting, poaching and unregulated hunting not stop now.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Sources; Cites, Red List, Wiki, Wild Forum, DEA, CCG, DSI, PHASA, Cambridge University, Oxford University.

Endangered Species Friday - Arborophila rufipectus

Endangered Species Friday - Arborophila rufipectus

This Friday’s endangered species I document on yet another species of bird that’s sadly been added to International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Bird Watch Project. Scientifically identified as the Arborophila rufipectus and commonly known as the Sichuan Partridge the species is listed as endangered - nearing extinction. (Image adult Sichuan Partridge). Listed as a nationally-protected species in China. In 1998, it was recorded in Mabian Dafengding Nature Reserve, where there was estimated to be 192 km2 of potentially suitable habitat.

Identified by Dr Boulton in 1932 the species falls into the phasianidae family. A. rufipectus is restricted to its endemic range of China from which its known to inhabit the south-central Sichuan, China with some sketchy reports of the species documented within Yunnan.

Reporting from Singapore where one of five of our Asiatic Bird Watch Projects are situated, environmental teams stipulated from their visits into China within the past fourteen months, no current camera trappings of the species have been recorded within its native range, or ranges where past census’s have been undertaken.

Furthermore the team exhausted all other searches by widening the search covering a total of 2,100 km2. Observations were undertaken in key areas where it was deemed the Sichuan Partridge may be inhabiting taking into consideration food sources, areas of forest that hadn’t been logged while communicating to local hunters, poachers and, locals within the area.

Graduate Lee Won - International Animal Rescue Foundation’s Bird Watch Project CEO stated “We covered an area over the 1,700 km2 setting camera traps within Sichuan and Yannan (2014-2015). The traps were in place for exactly 14 months of which not one single individual or even a pair of Sichuan Partridges were recorded, which brings me and the team to the conclusion that its quite possible extinctions have already occurred, western environmental organisations have as yet to catch up on this data”.

Lee Won and the team that are working within extreme environments stated that vast deforestation is increasing within the birds natural environment of which enforcement and environmental protection remains to be seen. “If Chinese authorities and the Department of Forests and Environment do not protect the Yunnan forests there will be little flora or fauna remaining within this area by 2030” Won stated. The situation is more than dire, its tragic Lee confirmed.

With populations still recorded as “decreasing” the last known census recorded from 1996-1997 recorded an “estimated” total of 806 to 1,772 mature individuals (final count stood at 1,500-3,749). So from Lee Won and his teams evaluations its quite possible that extinction has occurred of which evidence will be submitted in due course to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Dai bo (2007) stated that new sightings of the Sichuan Partridges have been recorded within Laojunshan Nature Reserve numbering around eighty four individuals, these sightings were recorded from 1998-2002. Kim Won’s Bird Watch Project will be making their way to the Laojunshan Nature Reserve in the next few weeks in the hope to locate any evidence of the birds present occupation within the area. Unfortunately we remain skeptical. As explained from 1996/7 population estimate is likely to be too low, hence it is best placed in the band 1,000-2,499 mature individuals. This equates to 1,500-3,749 individuals in total, rounded here to 1,500-4,000 individuals. (Source IUCN).

Males are territorial and monogamous. Males will stay away from the females before mating and during the incubation period. At all other times, males will roost alongside the females. While females are brooding on the ground, the males will sit near the ground for two weeks and then leave to roost elsewhere. The breeding season is late March while the hatching season is mid-May through mid-July. Once paired, males will guard females 24 hours a day.

Image: Sichuan Partridge fledgling.

When it comes to the general breeding and habitat locations for the partridge, it prefers more local areas far from direct disturbances from human contact. Males have three types of one-syllable call, which are a crowing call, courtship call, and preserving territory call. The syllable duration is significantly different between calls, but the difference of main peak frequency was not significantly different. The vocal behaviors will benefit to preserve mates and avoid the predator pressure so the population could last longer.

The Sichuan partridge lives mostly in southern Sichuan Province, in south-west China. It prefers primary and older planted secondary broadleaf forests, rather than one with human activity close by. Prefers a dense canopy and more open understory. The major habitats (in ranking order) are Primary Broadleaf Forest, old replanted Broadleaf Forest, Degraded Forest, and scrub. It prefers thick shrubs for roosting.

Recent work on the species in Laojunshan Nature Reserve found that the species occurred in secondary broadleaf forest but not in settlements, coniferous plantations or farmland [please note there remains no date regarding recent work]. The same study found that birds typically occurred between 1400 and 1800m above sea level in the reserve, and mostly on gently sloping ground close to water sources. [undated with citation required].

Major Threats

Until recently the main threat was habitat destruction through commercial clear-felling of primary forest, as most remaining primary broadleaved forest within its known range was at risk from logging within 20-25 years. In 1998, a government-imposed ban on logging in the upper Yangtze Basin led to a complete halt in deforestation throughout its range.

There is now a major forest plantation scheme in operation aiming to re-forest ridges and steeper slopes. In general though, habitat is still declining. In some areas, forest is still being cleared for agriculture or illegally logged, although this has been “alleged to be on a small scale”. Many people enter the forest to collect bamboo shoots, firewood and medicinal plants in spring and early autumn, which creates substantial disturbance during the breeding season, and additional disturbance is caused by livestock either grazing in, or moving through, the forest.

The species is also illegally hunted. Hydroelectric schemes and the resulting reservoirs in the valleys below its mountain forest habitat cause indirect future threats as the people they displace will be moved to higher locations in close proximity to the remaining forest, putting it under increased pressure.

Further assessments on the species and other endemic species will continue through to next year. I hope to update you on my teams current goals and objectives.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre.

www.speakupforthevoiceless.org

Please support the organisation Say No To Dog Meat this Malbok Festival from July to August 2015.