Endangered species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

Endangered Species Friday: Acinonyx jubatus

This Fridays endangered species I speak up about the now (not co common Cheetah). Endangered Species Watch Post (ESP) tries to limit the amount of commonly known specie on the platform, however due to recent declines we’ve now included the specie within the (ESP).

Listed on the ‘threatened list’ of (endangered species) as vulnerable, the common Cheetah was formally identified by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (1739 in Weißensee, Thuringia – 1810 in Erlangen), often styled I.C.D. von Schreber, was a German naturalist. (Image Cheetah, photographer unknown).

Identified back in 1775 there remains a total of some five sub-species known that inhabits north, south, west and east Africa. The sub-species A. j. venaticus is known only to inhabit Iran. Some very contradictory reports state there may or may not be populations living within Central India too.

From 1996 to 2002 A. jubatus populations haven’t increased of which this amazing hunting cat commonly known as the Cheetah or (Hunting Leopard) continues to sit at (vulnerable listing). Further population declines will most certainly see the specie qualifying for the category of (endangered). Should this occur the African Cheetah will become the first specie of big cat within the new millennium to hit endangered level.

Cheetahs have disappeared from some seventy six percent of their known historical range which now overtakes that of the Panthera leo (Lion). African populations are considered ‘widely common’ however still known to be sparsely populated. Meanwhile in Asia the Cheetah has practically vanished which is why we must do more to protect the last known remaining Africans populations before further extinctions occur. Cheetahs were known to be quite common throughout Mediterranean and the Arabian peninsula, north to the northern shores of the Caspian and Aral Seas, and west through Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan into central India However this is no longer the case.

One reason for for Asiatic Cheetah population declines was due to live captures of the animal which were trained to hunt other fauna. Unfortunately that was not the main reason why the specie spiralled into near extinction. The primary threat was Cheetah prey decline. This same problem has also been noted as effecting other big cats within Africa and Asia too. Agriculture, over-unregulated-hunting, over-culling, urbanization and habitat destruction via humans, has all played a significant role pushing the species furthermore into the realms of near extinction. Within Iran the sub-species A. j. venaticus is known to be (critically endangered)

In Tunisia Cheetahs were known to roam freely, however there are no known populations remaining within the country. The El-Borma region, near the Algerian boundaries, was probably among the areas where Cheetahs have last been seen in 1974 and documented. Reports compiled back in 1980 now tell us the specie is incredibly rare (if not regionally extinct already). Recently hunters yet again stated that (hunting) has never impacted on the species whatsoever. That’s a complete barefaced lie by members of (PHASA) Professional Hunting Association of South Africa and (DSI) Dallas Safari International.

Cheetahs became extinct from most of the Mediterranean coastal region and easily accessible inland habitats of El-Maghra and Siwa oases one decade after being widely distributed in the northern Egyptian Western Desert until the 1970s. The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands). Please view images lower down the article.

“The main reasons explaining cheetah extirpation have been attributed to (extensive and uncontrolled hunting and the development of coastal lands)”…

Current data on Cheetah population within Eritrea, Sudan and Somali is unknown. Populations within these three countries could very well already be extinct. Reports conducted within most “known Chad Cheetah zones” have sadly concluded the species is no longer present within the of much African country either, 2008 surveys did pick up few roaming species within Southern Chad though. Few populations remain within Central Sahara although to what extent is again unknown.

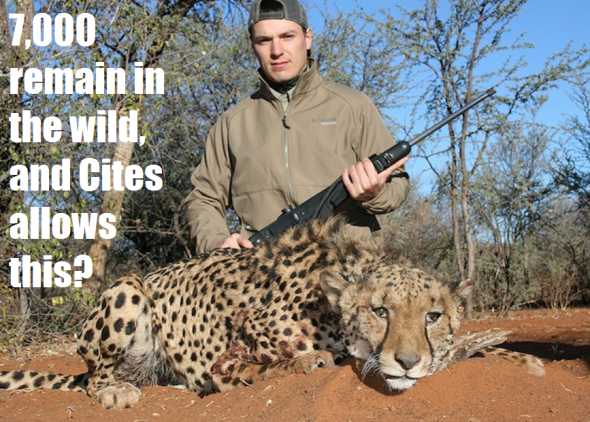

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Image: Hunter, Canada - 7,000 to 10,000 Cheetah remain and this is allowed by Cites.

Within the African countries of Cameroon, Central African Republic, Congo, and Democratic Republic of Congo again population counts are not known. (Its’ quite possible that the species has already gone extinct). Cheetahs are already officially extinct within Burundi and Rwanda. Reports have sadly confirmed the species is also extinct within Nigeria. Poaching and over-hunting have wiped all populations out within the three central African countries. A 1974 study ‘suggested’ that few populations may be occupying both Cameroonian boundaries and Yankari Game Reserve. This report is though mere speculation and not confirmed evidence.

EXTINCTIONS TO DATE

Regional Extinctions

Extinctions have already occurred within; Burundi; Côte d’Ivoire; Eritrea; Gambia; Ghana; Guinea; Guinea-Bissau; India; Iraq; Israel; Jordan; Kazakhstan; Kuwait; Oman; Qatar; Rwanda; Saudi Arabia; Sierra Leone; Syrian Arab Republic; Tajikistan; Tunisia; Turkmenistan; United Arab Emirates; Uzbekistan and Yemen.

Possible Extinctions

Afghanistan; Cameroon; Djibouti; Egypt; Libya; Malawi; Mali; Mauritania; Morocco; Nigeria; Pakistan; Senegal, Uganda and the Western Sahara.

Known Endemic Zones

Algeria; Angola; Benin; Botswana; Burkina Faso; Central African Republic; Chad; Congo; Ethiopia; Iran; Kenya; Mozambique; Namibia; Niger; South Africa; South Sudan; Sudan; Tanzania, United Republic of; Togo; Zambia; Zimbabwe. (Updated 2015)

2015 WILD POPULATION COUNTS

(Please note the following populations below are wild and not captive nor farmed)

Reintroductions of Cheetah populations have taken place within Swaziland however to what extent the populations are within Swaziland is unknown.

What we know to-date is that populations within the “Southern Africa” (not just South Africa) hosts the largest populations at roughly some 5,000+ mature individuals. Botswana and Malawi holds roughly 1,800 mature individuals. Populations are unknown within (Angola) and ‘considered possibly extinct’. Mozambique holds some 50-60 mature individuals, Namibia 2,000. SOUTH AFRICA holds some 550 mature individuals, Zambia some 100 mature individuals, Zimbabwe 400. A large proportion of the estimated population lives outside protected areas, in lands ranched primarily for livestock but also for wild game, and where lions and hyenas have been extirpated. So we do question why trophy hunting and unregulated hunting still persists out of farmed areas.

Ethiopia, southern Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania holds an estimated (2,500 mature individuals) however due to intense hunting pressure, poaching and habitat destruction this number could be much lower. (There is NO evidence that hunting within any of the ‘legal zones’ has increased Cheetah populations whatsoever”. Furthermore I challenge all hunting organisations within the legally allowed hunting areas to prove myself wrong? The largest population (Serengeti/Maro/Tsavo in Kenya and Tanzania) is estimated at 710.

Kenya hosts some 790+ mature wild individuals, Tanzania 560+ to 1,100 individuals. Uganda, Gros and Rejmanek (1999) estimated 40-295 with a wider range in the Karamoja region, whereas now Cheetahs have been extirpated and just 12 are estimated to persist in Kidepo National Park and surroundings. North-West Africa the species stands at no fewer that 250 mature individuals (if that).

Within Iran the ‘sub-species’ of Asiatic Cheetah - A. j. venaticus (if still extanct) stands at some 60-100 mature individuals. We do like the fact the conservation trustee is a known hunter allegedly supporting Cheetah conservation. We’ve yet to see an real improvement of Iranian Cheetahs in the country (more money talk)…

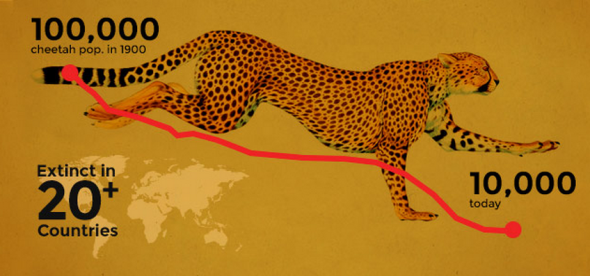

The overall “known Cheetah population” for Asia and Africa is by far more threatened that the Lion. To date there are some 7,000 known mature individuals remaining within the wild but no greater than 10,000. This sadly make the Cheetah by far more threatened than Panthera leo. African Lion populations stand at some 15,000 to 13,000 maximum. As the Cheetah population will not likely exceed 10,000 individuals - the species therefore qualifies for (vulnerable status).

Nowell and Jackson stated that Cheetah populations in the past have undergone some alarming declines, now it would seem that history is re-repeating itself (this time the specie may not survive). The Cheetah exhibits remarkable levels of genetic diversity in comparison and compared to other wild felids, so there could be a high chance the species may make it back from the near brink of extinction within the wild.

Problem is poaching and over-hunting then wasn’t as prolific as it is today. Scientists stated that interbreeding among other individuals had saved the species from bottleneck declines in the past. This history dated back some 10,000 years. Sport hunting then wasn’t an issue as it is today, so in all fairness the species could be hunted into extinction illegally or legally (with much thanks to Cites on the ‘legal part’). So in all honesty we may lose the Cheetah before the Lion.

While the causes of the Cheetah’s low levels of genetic variation are unclear [back then], what is clear is that large populations are necessary to conserve it. Since Cheetahs are a low density species, conservation areas need to be quite large, larger than most protected areas. Major areas of the African continent are being overtaken by humans, agriculture to cope with human expansion and deforestation. No longer is it a case of ‘if’ rather than ‘when’….

MAJOR THREATS

Cheetahs are ‘hunted for sport and trophies’, as well as handicrafts products. Live animals are also traded - the global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining. Pest animals are also removed.

In Eastern Africa, habitat loss and fragmentation was identified as the primary threat during a conservation strategy workshop (2007). Because Cheetahs occur at low densities, conservation of viable populations requires large scale land management planning; most existing protected areas are not large enough to ensure the long term survival of Cheetahs. A depleted wild ungulate prey base is of serious concern in northern Africa. Cheetahs which turn to livestock are killed as pests. Conflict with farmers and depletion of the wild prey base are also considered significant threats in parts of Eastern Africa.

In Iran, the Asiatic Cheetah A. j. venaticus is threatened indirectly by loss of prey base through human hunting activities. In addition, most protected areas are open to seasonal livestock grazing, which potentially places huge pressure on the resident ungulate populations through disturbance and potential competition. Additionally, domestic dogs accompanying the herds present a likely threat to both Cheetahs and their prey. An emerging threat is the possibility of fragmentation into discontinuous subpopulations as a result of increasing developmental pressures (mining, oil, roads, railways); this is particularly the case in Kavir N.P., currently the north-western limit of the Asiatic Cheetah’s range.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Image: Cheetah populations are more threatened than Lions.

Conflict with farmers and ranchers is the major threat to Cheetahs in southern Africa. Cheetah are often killed or persecuted because they are a perceived threat to livestock, despite the fact that they cause relatively little damage. In Namibia, very large numbers of Cheetahs have been live-trapped and removed by ranchers seeking to protect their livestock (from government permit records, Nowell [1996] calculated that over 9,500 cheetahs were removed from 1978-1995). While removal rates have fallen, in part due to intensified conservation and education efforts, many ranchers still view Cheetahs as a problem animal, despite research showing that Cheetahs were only responsible for [3% of livestock losses] to predators. Although Cheetah in Iran have been killed because of predation on livestock, since 2003, there has been no direct evidence of killing Cheetahs, though it is likely most incidents go unreported.

“Cheetahs are also vulnerable to being caught in snares set for other species”.

Another threat to the Cheetah is interspecific competition with other large predators, especially lions. On the open, short-grass plains of the Serengeti, juvenile mortality can be as high as 95%, largely due to predation by Lions. However, mortality rates are lower in more closed habitats.

CITES [allows legal trade in live animals and hunting trophies under an Appendix I] quota system (annual quotas: Namibia - 150; Zimbabwe - 50; Botswana - 5). This was accepted by CITES as a way to enhance the economic value of Cheetahs on private lands and provide an economic incentive for their conservation. The global captive Cheetah population is not self-sustaining; Cheetahs [breed poorly in captivity] and in 2001 [30% of the captive population] was wild-caught. While analysis of trade records in the CITES database shows that these countries have reported almost no live exports since the late 1990s, Conservation groups are concerned that there is a substantial illegal cross-border trade in live animals.

There is also concern about illegal trade in skins, as well as capture of live cubs for trade to the Middle East. There is an increasing trade in cubs from [north-east Africa into the Middle East], but there is currently little trade in cubs from the Sahel region, where it was previously considered a major problem. Cheetahs are active during the daytime and there is concern that they can be driven off their kills by [tourist cars crowding around, or mothers separated from their cubs]. Burney (1980) conducted a study and concluded that [tourist cars did not seem to harm cheetahs, and in fact sometimes helped, as cheetah chases more often ended in a kill when there were cars around, distracting prey, providing cover from which to stalk, or otherwise waking Cheetahs up to notice prey in the area]. However, [tourist numbers have risen sharply by then, and its potential impact on cheetahs remains a concern].

The Eastern African Cheetah conservation strategy identified four sets of constraints to mitigating these threats across a large spatial scale. Political constraints include lack of land use planning, insecurity and political instability in some ecologically important areas, and lack of political will to foster Cheetah conservation. Economic constraints include lack of financial resources to support conservation, and lack of incentives for local people to conserve wildlife. Social constraints include negative conceptions of Cheetahs, lack of capacity to achieve conservation, lack of environmental awareness, rising human populations, and social changes leading to subdivision of land and subsequent habitat fragmentation. These potentially mutable human constraints contrast with several biological constraints which are characteristic of Cheetahs and cannot be changed, including wide-ranging behaviour, negative interactions with other large carnivores, and potential susceptibility to disease.

Disease is a potential threat to the Cheetah, as its reduced genetic diversity can increase a population’s susceptibility. However, the most serious disease mortality thus far documented in wild Cheetahs was from naturally occurring anthrax in Namibia’s Etosha National Park; Cheetahs, unlike other predators, do not scavenge carcasses of ungulates killed by anthrax, and thus [had no built-up immunity] when they preyed upon springbok sick with the disease. The Cheetah’s low density may offer some measure of protection against infectious disease; for example, Cheetahs were not affected by an outbreak of Canine Distemper Virus in the Serengeti National Park which [killed over 1/3 of the Lion population]. Serological surveys of Cheetahs on Namibian farmland indicate some exposure and survival of the disease.

We are losing the Cheetah faster than the specie of Lion. Although some regulations are in place with the species listed on Appendix I (Cites) its quite likely we’ll lose wild populations should hunting, poaching and unregulated hunting not stop now.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Sources; Cites, Red List, Wiki, Wild Forum, DEA, CCG, DSI, PHASA, Cambridge University, Oxford University.

Endangered Species Friday: Anas melleri.

Endangered Species Friday: Anas melleri

This Fridays Endangered Species watch Post (ESP) focuses on a very undocumented bird known scientifically as Anas melleri and commonly known as the Meller’s Duck.

The Meller’s Duck was identified back in 1865 by lawyer and Doctor Philip Lutley Sclater FRS FRGS FZS FLS (4 November 1829 – 27 June 1913) was an English lawyer and zoologist. In zoology, he was an expert ornithologist, and identified the main zoogeographic regions of the world. He was Secretary of the Zoological Society of London for 42 years, from 1860–1902.

Listed as endangered, populations are on the decline quite extensively throughout the birds entire range. A. melleri qualified for (endangered status) back in 2012. Endemic to Madagascar the species can be located on the eastern and northern high plateau. Populations are isolated on massifs on the western edges of the plateau. Documented reports from the west of the island most probably refer to vagrant or most likely wandering birds.

Its been alleged that at some time from 2012 re-introduced populations on the island of Mauritius are now extinct - however there remains no hard hitting evidence to back this claim up, conservationists have stated that a ‘probable extinction’ occurred on the island.

The Meller’s Duck was once described as common on the Africans island of Madagascar, unfortunately there is no evidence to back this claim up either. Conservationists that visit the island regularly from International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa and have documented on the Meller’s Duck previously have been informed by locals that the species is rarely seen, however huntsmen will peddle the meat of ducks into local villages.

International Animal Rescue Foundation Africa stated the species had been documented by explorers as ‘densely populated’ on the island from the 1500’s to 1800’s. Sadly since human colonization increased on the island after the French protectorate from the mid 1800’s human population growth on the island has attributed to current decline of the species. Over the last twenty years human population has skyrocketed significantly which unfortunately has led to vast swathes of habitat destroyed and illegal poaching to occur.

“All birds seem to be within a single subpopulation which is probably continuing to decline rapidly. Extinctions are likely to occur in under a few years, five years max”…

Conservation teams like the local communities have confirmed that the species is sadly no longer common ‘anywhere’ other than forested areas of the northwest and in the wetlands around Lake Alaotra where there are some breeding pairs, but where many non-breeders collect, with up to 500 birds present. All birds seem to be within a single subpopulation which is probably continuing to decline rapidly. Extinctions are likely to occur in under a few years, five years max!.

Population sizes are incredibly depressed. We now know the species numbers at 2,000 to 5,000 individuals which equates to exactly 1,300 to 3,300 mature individuals. Should pet collection, poaching, habitat destruction Etc continue at the rate it is extinctions will as explained occur in roughly (730 days). That’s how serious the problem is.

Conservation projects are underway of which the IARF have contributed funding towards the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. The species occurs in at least seven protected areas, and is known from 14 Important Bird Areas (78% of eastern Malagasy wetland IBAs) (ZICOMA 1999). No regular breeding sites are known. In 2007, there was a drive to increase the number of institutions that keep the species in captivity, and as such the bird is a nationally protected species.

Conservation actions planned: Protect remaining areas of least-modified wetlands at Lake Alaotra. Conduct wide-scale status surveys of eastern wetlands. Study its ecology to identify all causes of its decline and promote development of captive breeding programmes.

(Please note all new monetary and equipment grants provided by IARFA from August of last year to present has yet to be updated into the main transparency register onsite)

Meller’s duck breeds apparently during most of the year except May–June on Madagascar, dependent on local conditions; the Mauritian population has been recorded to breed in October and November (however as explained is likely to now be extinct). Unlike most of their closer relatives—with the exception of the African black duck—they are fiercely territorial during the breeding season; furthermore, pairs remain mated until the young are.

Threats

A. melleri is still classed as the largest species of wildfowl found in Madagascar and is widely hunted and trapped for subsistence (and for sport). Interviews with hunters at Lake Alaotra suggest c.450 individuals are taken each year, constituting 18% of the global population.

Long term deforestation of the central plateau, conversion of marshes to rice-paddies and degradation of water quality in rivers and streams, as a result of deforestation and soil erosion, have probably contributed to its decline too. Widespread exotic carnivorous fishes, notably Micropterus salmoides (although this may now be extinct) and Channa spp., may threaten young and cause desertion of otherwise suitable habitat.

Its decline on Mauritius has been attributed to hunting, pollution and introduced rats and mongooses as well as possible displacement by introduced Common Mallard Anas platyrhynchos. Pairs are very territorial and susceptible to human disturbance.

Extinction is likely to occur of which continued protective captivity projects must increase for the birds future survival and re-introduction elsewhere.

The video below depicts a Meller’s Duck captivity project in Germany.

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

http://www.speakupforthevoiceless.org

Please donate to SAYNOTODOGMEAT.NET < Click the link - [email protected]

Endangered Species Friday: Ailurops ursinus

Endangered Species Friday: Ailurops ursinus

A. ursinis was identified back in 1824 by Dutchman Dr Coenraad Jacob Temminck - (31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist, and museum director. Listed as vulnerable the species is endemic to Indonesia on the island of Sulawesi of which there remains limited data on this rather fine specimen of marsupial that resides in the family phalangeridae. (Image: Young Bear cuscus)

Populations of the (Bear cuscus) as its commonly known continue to steadily decline even though there are limited - conservation measures in place protecting the species (There remains as yet no data on population size). The Bear cuscus has practically gone extinct within the Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve of which a staggering 95% decline has been recorded within the region alone of which the primary threat within the nature reserve is hunting and trade for pets.

North Sulawesi has also seen a staggering decline identical to the population decreases documented within the Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve too. Yet again hunting and the illegal pet trade are very much responsible, and may very well within the next five to ten years lead to a complete extinction occurring.

As much as I myself hate to say it I am pretty certain from viewing statistical data past and present that extinctions are going to occur even sooner than predicted. Should extinctions occur it proves yet again that poaching is having a disastrous effect onto just about every African and Asian species known.

Habitat loss and forest clearance are all playing a pivotal roll at decreasing populations of this beautifully attractive marsupial. As a conservation and botanical scientist sometimes I wonder to oneself why we even bother to help species of animals and flora when some governments show no support, or respect whatsoever in our quest to protect and serve. Then I remember, my children and their children’s heritage is just as important as mine and the teams fight to protect.

Bear cuscus are known as arboreal marsupials meaning, they mostly thrive and spend the majority of their peaceful and playful lives within trees and dense forest. Unfortunately these forests and trees are slowly dwindling in size primarily for land clearance to support local farms and communities and, not forgetting slash and burn activities. I cannot begin to imagine what these creatures think and feel when destructful and greedy humans destroy their homes and pastures. The feeling of not-knowing-when such harm is to be inflicted must be terrorizing for them.

The genus contains the following single species that is known to be related to the Bear cuscus; Ailurops melanotis that inhabits the Salibabu Island listed as (critically endangered) and endemic to Indonesia on the island of Sulawesi. Typically found in undisturbed tropical lowland moist forests, this species does not readily use disturbed habitats, thus it is not usually found in gardens or plantations. It is a largely diurnal and as explained a arboreal species that is often found in pairs. Diet usually consists of a variety of leaves, preferring young leaves, and like many other arboreal folivores it spends much of its day resting in order to digest similar to the Koala bear of Australia.

Image: Bear cuscus relaxing in the canopy of Tangkoko

The only known conservation actions that are taking place are within in few protected areas, that include: Tangkoko-DuaSudara Nature Reserve, Bogani Nani Wartabone National Park, Lore Lindu National Park, Morowali National Park, and a host of forest reserves. This species is nominally protected by Indonesian law. Unfortunately even though the species is protected the illegal pet trade still continues of which I myself have on many occasions located small pet shops in Indonesia selling Bear cuscus from rusty, cramped cages.

Threats

The species is threatened by habitat loss due to clearance of forest for small-scale agriculture and through large-scale logging. It is also heavily hunted by local people for food, and collected for the pet trade. Cuscus hunting forays are often planned before special occasions (e.g., birthday celebrations) in order to provide future guests with the greatly appreciated meat. (These inferences are based on some six months of residence among Alune villagers in 1993–95, which included participation in forest activities and standard ethnographic data collection.)

Thank you reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre

Environmental and Botanical Scientist.

Please donate by clicking the link below and help the board of directors establish their Viet Nam pet and wildlife rescue and rehabilitation clinic today. Without your help we cannot take dogs, cats and small bush meat animals of the streets and into safety. No donation is to small and all donations are greatly and kindly appreciated.

Please donate here:

https://www.facebook.com/SayNoToDogMeat/app_117708921611213

Stay up to date with our SNTDM newsletter:

https://www.facebook.com/SayNoToDogMeat/app_100265896690345

Thank you.

Stay up to date with African and international environmental and animal welfare affairs here:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/International-Animal-Rescue-Foundation-World-Action-South-Africa/199685603444685?fref=ts