Corroboree Frogs - Critically Endangered

Corroboree Frogs are amongst the most visually spectacular frogs in the world and are Australia’s most iconic amphibian species. Listed as critically endangered, the two species have several differences between them, including colour, patterns and even skin biochemistry.

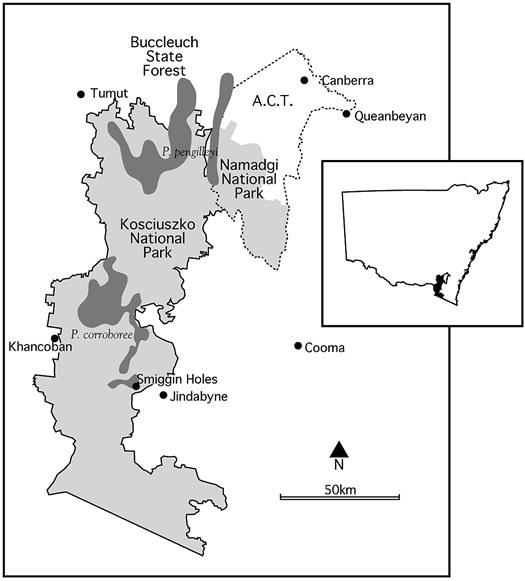

The frogs are around 3centimetres in length and only live in the sub-alpine regions within Kosciuszko National Park, from Smiggin Holes in the south, and northwards to the Maragle Range. Southern Corroboree Frogs only occur between about 1300 and 1760 m above sea level.

Breeding

Habitat which is critical to the survival of Corroboree Frogs includes both breeding habitat and nearby areas where they feed. The frogs have to be four years old before they can begin to reproduce and adults only have one breeding season around December, when males build chamber nests within grasses and moss near shallow pools, seepages and so on.

Corroboree Frogs tend to breed in water bodies that are dry during the breeding season. Outside the breeding season, Corroboree Frogs have been found sheltering in dense litter and under logs and rocks in nearby woodland and tall moist heath. Northern Corroboree Frogs have been found to move over 300 metres into surround woodland after breeding.

The diet of Corroboree Frogs consists mainly of small ants and, to a lesser extent, other invertebrates. Typically, the pools are dry during the breeding season when the eggs are laid. The males have three call types: an advertisement call, threat call, and courtship call.

Males woo their lady-frogs by singing. Each male will attract up to ten females to his burrow sequentially and may dig a new burrow if his first is filled with eggs.

If a female is attracted to a male, she will lay her eggs in his nest. The male will remain in his nest through the breeding season and may accumulate many clutches. Clutch size for Corroboree Frogs is relatively low for a frog species; 16 to 38 eggs per female.

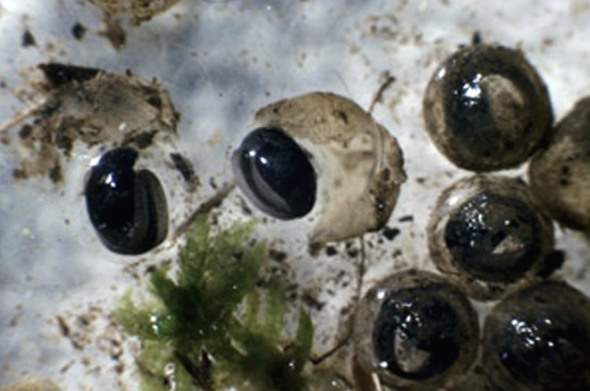

Within the nest, the eggs develop to an advanced stage, before development stops and they enter what is called ‘diapause’. This effectively means that the embryos remain, without developing further, until flooding of the nest following autumn or winter rains stimulates them to hatch.

After hatching, the tadpoles move out of the nest site and into the adjacent pool where they live for the remainder of the larval period as a free swimming and feeding tadpole. Corroboree Frog tadpoles are dark in colour, have a relatively long paddle shaped tail, and grow to 30 mm in total length. The tadpoles continue growing slowly, particularly over winter when the pool may be covered with snow and ice, until metamorphosis in early summer.

Corroboree frogs are the first vertebrates discovered that are able to produce their own poisonous alkaloids, as opposed to obtaining it via diet as many other frogs do. The alkaloid is secreted from the skin as a defence against predation, and potentially against skin infections by microbes. It has been described as potentially lethal to mammals if ingested. The unique alkaloid produced has been named pseudo-phrynamine.

Corroboree frogs hibernate during winter under whatever shelter they can find. This may be snow gum trees, or bits of bark or fallen leaves. Males stay with the egg nests and may breed with many females over the course of one season.

Conservation status

Both species have declined dramatically in the past thirty years. However, the Southern Corroboree Frog has suffered from more serious declines.

Current status

The Southern Corroboree Frog, as of June 2004 had an estimated adult population of 64. This species has suffered declines of up to 80% over the past 10 years. It is found only within a fragmented region of less than 10 km² within Mount Kosciuszko National Park in the Snowy Mountains in New South Wales. It is only found at 1300 m above sea level (Osborne 1989). It is currently listed as critically endangered and is considered to be one of, if not, Australia’s most endangered species.

The Northern Corroboree Frog is more widely distributed across about 550 km² of the Brindabella and Fiery Ranges in Namadgi National Park, Australian Capital Territory, and Kosciuszko National Park and Buccleuch State Forest in New South Wales. It is found above about 1000m and is found to have higher population numbers at lower elevations. It has recently been downgraded from critical to endangered by the IUC finding.

Cause for decline

The near-loss of these frogs has been attributed to a variety of causes, such as habitat destruction from recreational 4WD use; development of ski resorts; feral animals; degradation of the frogs’ habitat; the extended drought cycle affecting much of southeastern Australia at present; and increased UV radiation flowing from ozone layer depletion.

The drought affects these frogs by drying out their breeding sites so that the breeding cycle, which is triggered by seasonal changes and may require moistening of the bogs in autumn and spring to bring on specific developmental events, is delayed. This may mean that tadpoles have not metamorphosed by late summer when their bogs dry out, and so perish. The bogs themselves are apparently drier than usual.

Severe bushfires in the Victorian and NSW high country in January 2003 destroyed much of the frogs’ remaining habitat, especially the breeding sites and the leaf litter that insulates overwintering adults. The fire affected almost all Southern Corroboree Frog habitat, however recent surveys have shown that the fire resulted in a lower than expected decline in population.

As with many other Australian frogs, the predominant reason for the Corroboree Frogs’ decline is thought to be infection with the chytrid fungus. This fungus is believed to have been accidentally introduced to Australia in the 1970s and destroys the frogs’ skin, usually fatally. Corroboree frogs’ eggs appear to be immune. Frog populations may eventually be able to acquire immunity, as wild relatively healthy adults have been found with the fungus on their skin.

Conservation efforts

The Amphibian Research Centre had already begun a rescue programme under which eggs were collected and raised to late tadpole stage before return as close as possible to their collection site. Research is now underway into captive breeding and on which lifecycle stage - eggs, tadpoles or adults - promises the best chance of survival following return to the wild.

The national parks authorities in the Australian Capital Territory, New South Wales and Victoria have developed conservation programmes, including a captive husbandry programme at Tidbinbilla, ACT, Taronga Zoo in Sydney, as well as Zoo’s Victoria at Healesville Sanctuary.

The two species are the Southern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree) and the Northern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne pengilleyi).

To read more on Corroboree Frogs and how to help them: www.corroboreefrog.com.au

Thank you for reading.

Michele Brown.