Endangered Species Monday | Tasmanian Devil | Sarcophilus harrisii.

ENDANGERED SPECIES MONDAY | TASMANIAN DEVIL

This Mondays endangered species watch post (ESP) is dedicated to the Tasmanian devil, an endangered carnivorous marsupial that’s roughly the same size as a small domesticated canine. (Image credits: Bicheno Tasmania tourism)

The Tasmanian devil was formally identified back in 1841 by ‘French’ Dr Pierre Boitard (27 April 1787 Mâcon, Saône-et-Loire – 1859) whom was a French botanist and geologist. As well as describing and classifying the Tasmanian devil, he is notable for his fictional natural history Paris avant les hommes (Paris Before Man), published posthumously in 1861, which described a prehistoric ape-like human ancestor living in the region of Paris. He also wrote Curiosités d’histoire naturelle et astronomie amusante, Réalités fantastiques, Voyages dans les planètes, Manuel du naturaliste préparateur ou l’art d’empailler les animaux et de conserver les végétaux et les minéraux, and Manuel d’entomologie etc.

Listed as (endangered), and scientifically identified as Sarcophilus harrisii. Back in 1996 conservation scientists undertook further research on the species thus concluding the species was of ‘lower risk’. Unfortunately since 1996 - things have changed dramatically on the Australian continent. From the middle 1990’s conservationists estimated the mean mature individual total as being - 130,00-150,000 mature individuals.

Spotlighting sightings of Tasmanian devils across the state have declined significantly since the emergence of Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) in the mid-1990s: by 27% by early 2004, by 41% by early 2006, by 53% by early 2007, and by 64% by early 2008. The decline was significantly sharper in regions where DFTD had been reported earliest, such that in north-east Tasmania, mean sightings have declined by 95% from 1992-1995 to 2005-2007, with no indication of recovery or plateau in decline.

Comparison of mark-recapture results in the same area from the mid-1980s and 2007 supports this finding. At the Freycinet peninsula, on the east coast of Tasmania, where the population has been monitored through trapping from 1999 to the present, the population has declined by at least 60% since the disease was first detected in 2001 and the adult population still appears to be halving annually. Other indicators of devil abundance, such as road kills, predation on stock, and carrion removal, also support this conclusion of a substantial decline.

Surveys conducted back in 2007 ‘estimate the (mature) Tasmanian devil populations to be standing 25,000 being the highest estimate’; this equates to around 50,000 individuals. However back in 2004 conservationists stated the (mature populations) could be as low as 21,000 mature individuals. Conservationists have confirmed that due to the rapid spread of Devil Facial Tumor Disease, and other threats such as road accidents and predator kills - acknowledging these provisos, the best estimate of total population size based on current evidence thus lies within the range of 10,000-25,000 mature individuals. Based on threats, gestation, life span this therefore qualifies the species to be entered into [endangered category].

13 Feb 2011, Cradle Mountain-Lake St. Clair National Park, Tasmania, Australia — Tasmanian Devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) being treated by scientist for DFTD, Devil Facial Tumor Disease. This is a cancer that is spread by biting or physical contact from one animal to another, Cradle Mountain, Tasmania, Australia. — Image by © Dave Wattsl/Visuals Unlimited/Corbis.

In North-Western Australia Tasmanian devil populations are estimated to be standing at between (3,000-12,500 individuals). Meanwhile - in Eastern South Western Australia populations are said to be standing at 7,000 12,500 individuals.

Other trapping work by the Department of Primary Industry and Water (DPIW) Save the Tasmanian Devil Program broadly support these predictions for DFTD-free regions. However, in central and eastern regions, marked population declines have been detected, in association with the earlier reports of Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD), subsequent to the time of the Jones and Rose survey. The north-west region is thus now thought to support the highest population densities.

The species is not known to be seriously or severely fragmented, however populations on the decline and fast, primarily due to Devil Facial Tumor Disease.

THREATS

Current evidence suggests that DFTD is an infectious, widespread disease, so that any attempt to delineate boundaries between affected and unaffected locations is likely to be outdated swiftly. DFTD has been associated with local population declines of up to 89% since first reported (Hawkins et al. 2006, McCallum et al. 2007), indicated by long-term spotlighting data, widespread trapping and laboratory results. The declines, and the prevalence of the disease, have not eased off in any monitoring sites, and DFTD is present even in very low density areas.

It is estimated that the adult population is approximately halving annually on the Freycinet peninsula with extinction predicted at this site 10-15 years after disease arrival. Declines were most marked in areas where the disease had been reported earliest, in north-eastern and central eastern Tasmania.

Mean spotlighting sightings of Tasmanian devils per 10 km route, obtained from across the core Tasmanian devil range (eastern and north-western Tasmania), have declined by 53% since the first report of DFTD-like symptoms in 1996. The most immediately threatened location is thought to be the region where DFTD was reported prior to 2003: across 15,000 km² of eastern Tasmania.

By 2005, the Devil Disease Project Team had confirmed DFTD in individuals found across 36,000 km² of eastern and central Tasmania. DFTD is now confirmed across more than 60% of the devil’s overall distribution, and there is evidence for continued geographical spread of the disease, so that Tasmanian devils across between 51% and 100% of Tasmania may be, or have already been, subject to >90% declines in a ten-year period. The currently affected region covers the majority of the formerly high-density eastern management unit, involving what was perhaps around 80% of the total population.

Image: Tasmanian devil killed by car/with suspected DFTD.

DTFD has resulted in the progressive loss of first the older adults from the population and then the younger adults so that populations are comprised of one and two year old’s. As female devils usually breed for the first time at age two, they may not successfully raise a litter before they die of DFTD. An increase in precocial breeding indicates some compensatory response, but as yet this appears to have been insufficient to counter mortality.

DFTD behaves like a frequency-dependent disease, probably because the majority of the injurious biting, which is the type of contact most likely to lead to disease transmission, occurs between adults during the mating season. Frequency-dependent diseases, which are typically sexually transmitted, can lead to extinction. Because transmission occurs between the sexes at mating irrespective of population density, these types of diseases lack a threshold density below which they become extinct.

Cannibalism is considered fairly common in Tasmanian devils and renders the species particularly vulnerable to disease transmission. However, modes of transmission of DFTD are not as yet known.

ROAD KILLS:

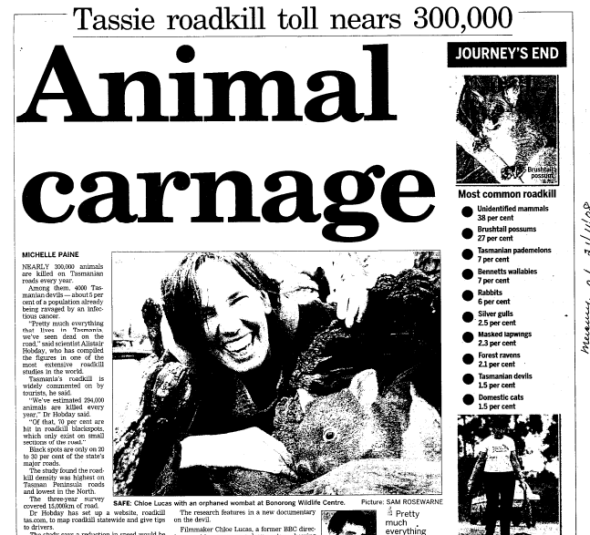

A recent three-year study of roadkill frequency on the main roads of Tasmania estimated 2,205 Tasmanian devils are killed on roads annually. This suggests that 2-3.% of the total Tasmanian devil population are killed on roads (based on an estimated population of 60,000–90,000 individuals at the time of the survey). The roaded parts of Tasmania closely match the core distribution area for Tasmanian devils.

Roadkill was attributed as the cause of up to 50% and 20% of Tasmanian devil death during a recording period of 17 months at Cradle Mountain and 12 months at Freycinet National Parks, respectively. Local extinction and a similar rate of population decline at Cradle Mountain indicates that roadkill can cause local extinction, in which the road becomes a local sink. Future impact is likely to remain at the same level.

Image: Paper cutting relating to 3 year study of fauna road kill.

DOG KILLS:

Reports of about 50 devils killed per year by poorly controlled dogs are served from about 20 dog owners. There is no obligation or incentive for such reports, and generally some hesitance even among those providing them, so the real figures are more likely of the order of several hundred devils killed by dogs each year.

FOXES:

There have been spasmodic, small-scale introductions of the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) into Tasmania since early European colonisation. Early incursions were sometimes efforts at acclimatisation and others for short-term hunting. More recently, there has been at least one accidental incursion (from a container ship in 1998) and credible reports of a concerted, malicious campaign of introduction.

Hard evidence (confirmed scats, carcasses) of foxes has been found in the north-west and northern and southern midlands. Credible sighting reports have come from most of the eastern half of the State including the central highlands and the far north-west, mostly areas where Tasmanian devil populations are suppressed by DFTD.

A commonly held view has been that the abundance of Tasmanian devils has prevented fox establishment through interference competition, either aggressive exclusion or predation on denned juveniles. Red Foxes and Tasmanian devils share preferences for den sites and habitat, and are of a similar size. Tasmanian devils abundance is likely to slow, if not prevent, fox establishment.

It is possible that foxes have been present in Tasmania for many decades at sub-detectable levels, and that a degree of ecological release has occurred due to DFTD, with foxes increasing to detectable numbers. The current impact of the Red Fox has been quantified, and it is unlikely that fox numbers are currently at a level to impose a measurable impact.

A decline in Tasmanian devils number may create a short to medium-term surplus of food, for example carrion; ideal for fox establishment. Fox establishment may cause both direct and indirect effects on Tasmanian devils. Direct effects include (reciprocal) killing by then abundant foxes of then rare juvenile devils at dens while the female forages.

Fox establishment may also cause ecosystem disruptions through changes in other species - a feature of foxes on mainland Australia and something that might then also indirectly affect Tasmanian devils. Tasmania has the potential to hold up to 250,000 foxes (based on modelling of habitat preferences and densities in south-east mainland Australian) which could replace most medium- to large-sized marsupial carnivores.

Image: Red foxes have been reported to prey on Tasmanian devils/Other Marsupials.

PERSECUTION:

In the past, persecution of the Tasmanian devil has been very high throughout settled parts of Tasmania, and is thought to have brought about very low numbers at times. Through the 1980s and 1990s, systematic poisoning in many sheep-growing areas (particularly fine-wool with its reliance on merinos) was widespread and probably killed in excess of 5000 devils per year. In the 1990s, control permits were occasionally issued to individuals who were able to argue that Tasmanian devils were pests (e.g. killing valuable lambs).

Current persecution is much reduced, but can still be locally intense with in excess of 500 devils thought to be killed per year. However, this is reducing since devil numbers have declined. While the small amount of current persecution is likely to persist it is unlikely to constitute a major threat unless the Tasmanian devil population becomes extremely small and fragmented.

LOW GENETIC DIVERSITY:

Dr Jones in 2004 found the genetic diversity of Tasmanian devils to be low relative to many Australian marsupials as well as placental carnivores. This was consistent with an island founder effect, but previous marked reductions in population size may also have played a role. Low genetic diversity can reduce population viability, and resistance to disease.

Image: Tasmanian devil (photographer unknown).

Tasmanian devils normally eat birds, snakes, fish, reptiles and insects. Furthermore its not uncommon to witness the species feasting on dead carrion. Female devils will mate with dominant males, who fight to gain their attention. Three weeks after conception, the females ‘can’ give birth to up to FIFTY BABIES, called joeys, although some reports state between 20-30 joeys. These extremely tiny joeys scramble to attach themselves to one of the four available teats in the mother’s pouch. Gestation is around 21 days.

For now the future is uncertain with regards to the Tasmanian devil. The species hosts a large number of natural threats, as well as roadkill accidents, human persecution and (DFTD). For now populations are considered to be generally high, although not that high for the species to qualify as vulnerable, or even near threatened. There are a number of Australian marsupials facing many threats, despite the continent being inhabited at some 10% by humans, or to be precise - 768,685 km2.

While I myself cannot state for certain what the future may hold for the Tasmanian devil - for now based on the large number of threats and continued population declines - its highly likely that come 2026 we’ll be seeing yet another Australian extinction occurring under our noses, and that is the sad reality of life from which our wildlife is facing today.

One thing is for sure though - never underestimate the DEVIL - they’re not called devils for nothing and have a rather cute temper too. Welcome to the planets largest carnivorousness marsupial. The Tasmanian devil

Thank you for reading.

Dr Jose C. Depre PhD. MEnvSc. BSc(Hons) Botany, PhD(NeuroSci) D.V.M.

Master Scientist of Environmental, Botanical & Human Science

Thank you for your reply, should it merit a response we will respond in due course. This site is owned by International Animal Rescue Foundation and moderation is used.